The Paradoxes of Global History

The Paradoxes of Global History

Francesca Trivellato

Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton

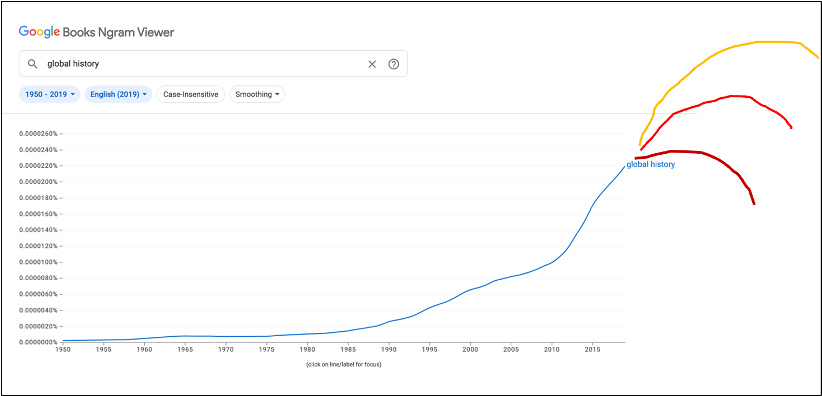

The contributions to this forum, ‘On Global Historical Writing and Scholarship,’ are symptomatic of a larger tendency: global history elicits as much enthusiasm as skepticism. [1] This is certainly true in the corners of the North American and European academic world with which I have some familiarity. Hang around historians and you will find that many believe that global history is subjected to the law of diminishing returns (Figure 1). David Bell, who has his fingers on the pulse of scholarly trends, already wrote as much a decade ago. [2] Most do not know when global history will hit its inflection point, but are confident that the time will come. Those who wish that by now it had arrived tend to mumble such thoughts, although a few have spoken loudly and clearly. [3]

The reasons for this murmuring dissatisfaction with global history, however, are not always clear. Some lament the fact that global history conjures up irenic views of cross-cultural fertilisation and connectivity at the very moment when we are surrounded by skyrocketing economic inequality, racism, warfare, and authoritarianism. [4] But this idealisation is only part of the problem. As Christopher Bayly reminds us, phenomena that tear the world apart, including xenophobic nationalism, religious fundamentalism, and economic protectionism, can and ought to be understood in a global, connected, and comparative perspective. [5] Others, as we will see, have raised more severe objections against the global turn, including its unescapable Eurocentric epistemics.

Figure 1. Google, Google Books Ngram Viewer, ‘global history,’ (1950–2019), English (2019).

Unable and unwilling to make predictions, I will refrain from forecasting what the trajectory of global history might look like in an N-Gram visualisation that extends past 2019. Rather than looking at the future, I suggest that we remain firmly in the present and take stock of the recent past. Doing so will compel us to admit that global history is caught in a series of paradoxes, of which four stand out:

- we cannot define global history and yet it is the most common referent in current historiographical debates;

- we cannot define global history but we institutionalise it (as in the name of degree programs, centres, book series, etc.);

- we cannot define global history but we debate its pros and cons;

- we cannot define global history but we leverage a series of antinomies to debate its supposed pros and cons (e.g., local vs global; micro vs macro; short vs long duration; case studies vs generalisations).

There is something slightly embarrassing about the crudeness of this list. But I offer it as a canvas and a springboard, a means of harnessing and shifting some of the conversations that are ongoing in the classrooms and corridors of history departments the world over, as well as on social media and, to a lesser extent, in print.

Of course, the only reason to engage in such an exercise of collective self-examination is the hope that the more we pry open these paradoxes, the more we can move beyond them. Given that hope implies the existence of a future, my modest proposal, too, involves a projection into the future. But I insist on my diagnostic rather than prescriptive motivation. I am not invested in saving or killing global history or finding a cure for its indeterminacy and ambiguities, as much as in laying bare and interrogating these paradoxes.

To anticipate my argument, peeling away at these paradoxes reveals that when we speak of global history, we often conflate subject-matter and method. This conflation strikes me as ever more widespread in today’s historiographical practice. In fact, global history is neither a stable subject-matter nor is it a method. Whatever it is, global history has prompted and can continue to prompt us to broach new questions. A question is far from an answer, that much we have to recognise. But a new question is a good beginning.

Paradox no. 1: We cannot define global history and yet it is the most common referent in current historiographical debates

I am hardly the first person to ask: what is global history? Indeed, this is the title of the recognised primer in the field. [6] This is not the place to compile all the definitions that have been given (though such a compilation would likely disclose interesting patterns). On the basis of an incomplete sampling, it seems fair to say that no attempt at defining global history has been conclusive. Dominic Sachsenmaier, holder of a chair in ‘Modern China with a special Emphasis on Global Historical Perspectives’ at the Georg-August-University of Göttingen, is among those who have sought to offer particularly capacious renditions of the genre while also inquiring into its manifestations in different countries and continents (a point to which I will return). [7] In his words:

‘Global history’ refers to a wide range of research approaches that are typically characterized by a rising interest in alternative conceptions of space beyond methodological nationalism and Eurocentrism. It builds on a multitude of detailed research branches of historiography, ranging from economic history to cultural history and from gender history to environmental history. Unlike in the case of intellectual movements such as subaltern studies or world systems theory, global history did not emerge from a core political agenda or societal commitment. Rather, it rose to significance as a rather diffuse – and initially often unnoticed – research trend across a wide variety of research communities. [8]

There is a lot that could be unpacked in these few lines. For our purposes, let me highlight four points. First, global history is said to consist of ‘a wide range of research approaches.’ Second, to the extent that something holds together this variegated galaxy, it is a negative rather than a positive catalyst (the opposition to ‘methodological nationalism and Eurocentrism’). [9] Third, global history is described as an overarching label that does not displace more traditional sub-disciplinary headings, such as economic or gender history. Finally, following Sachsenmaier, global history lacks ‘a core political agenda or societal commitment.’

The vagueness and incompleteness of this definition makes it, in my view, compelling, if not even exemplary. This is the first paradox we need to grapple with.

Against the tendency to admit (more or less openly) that global history does not cohere in the ways in which we used to think about historiographical trends, there are those, notably Lynn Hunt, who called it a paradigm shift in the proper Kuhnian sense on par with the ‘four major paradigms of historical research in the post-World War II era: Marxism, modernization, the Annales school, and, in the United States especially, identity politics.’ [10] Of course, Hunt knows that Marxist historians fought acerbically among each other and that there was no unified Annales school, let alone a single approach to what might constitute identity politics. But she deploys her keen eye in the service of drawing a usable roadmap of meandering historiographical labyrinths.

My purpose goes in the opposite direction and aims to stress the confusion that lurks under the umbrella of global history. The other four ‘paradigms’ that Hunt lists provide a useful contrast insofar each one has greater unifying traits, as well as landmark if not foundational works. Their relative coherence only highlights the extent to which global history is ill-defined even by the metrics of Western historiography. Compared to philosophers, critical theorists or quantitative social scientists, the vast majority of historians is comfortable with fairly loose discussions of methodology. Several actually take pride in the discipline’s empiricism and resistance to strict definitions, when they are not openly averse to anything that smacks of ‘theory’ (whatever that means). There are, of course, intellectual historians who discuss the philosophies of history that underpin various reconstructions of the past. But most of us toss around a variety of words without much precision: disciplines, fields, approaches, methods, perspectives, ‘branches of historiography’ (as per Sachsenmaier), and the now ubiquitous ‘turns.’ [11]

Global history feeds on this tendency and exacerbates it. It is the talk of the town but we cannot really say what it is. It elicits strong feelings—when not very strong feelings—but generates no consensus. Politically, it maps onto the entire spectrum, from left to right, with apologists of the British Empire adopting the label almost as often as its unabashed critics. [12] Nor can global history be defined thematically: it accommodates slaves and ‘disposable people’ as well as bodies of international governance and their leaders. [13]

Most tellingly, global history lacks a canon. In the fall of 2020, Lucy Riall and Giorgio Riello convened a doctoral seminar in Global History at the European University Institute (EUI) that had by then become a fixture (see paradox no. 2). Under pressure from a world-wide pandemic that froze everyone in place and exposed the depth of structural inequalities and prejudice, students in the seminar took the lead and produced a remarkable document: an impassioned indictment of the role that Anglophone publishers and academic institutions (EUI included?) play in hijacking the supposedly good intentions of global history, turning it into yet another instrument of the Global North’s soft power over the Global South. Published in this forum under collective authorship, the paper retains a raw quality that captures with unusual freshness dilemmas facing most doctoral students today. [14]

Invertedly, the paper also unveils for us a quandary that is often concealed. Among the participants, we are told, some were ‘charmed’ and others ‘repelled by global history’ (note the strong verbiage used here), but all ‘were interested in the methods and problems of global history.’ Yet, the authors soon discovered that ‘there is nothing canonical about global history: indeed, since its establishment in 2009, the EUI Global History seminar has altered so dramatically that not a single reading from the 2009 syllabus is on the syllabus for 2020.’

There is something very powerful in this candid admission, something that we should not discount as the naiveté of junior scholars but rather make into our collective conundrum. All too often the sense of confusion and frustration that is aired informally does not make it to the printed page. A series of interviews with distinguished practitioners and interpreters of global history that is freely available online brings home the point. Every interviewee invariably admits how difficult it is to define global history, to an extent that far exceeds the ways in which the problem is addressed in their respective publications. [15] Evidently, when it comes to global history, the Aristotelian dichotomy between writing and orality continues to cast a long shadow. In talking about it, we are ready to pause on the uncertain and contradictory quality of this rubric, while when we write, we organise our puzzlement under more or less convincing classifications (see paradoxes nos 3–4).

Paradox no. 2: We cannot define global history but we institutionalise it

In spite of its nebulous, even incongruous nature, we rush to institutionalise global history. The expression has become the name of choice for countless academic centres, degree programs, book series, journal titles, and much more. Not to speak of the adjective global, which is now literally ubiquitous. At the University of Cambridge, a well-regarded M.Phil. programme maintains the older label of ‘world history,’ while the Press titles a book series ‘Global and International History.’ [16] These oscillations are less telling than the way in which the institution as a whole fashions itself: its website has a tag ‘Global Cambridge,’ which reads: ‘The University of Cambridge is a global institution. These pages provide an overview of Cambridge’s international activities in pursuit of its mission to contribute to society through excellence of education, learning and research.’ [17]

This self-description (of which it would be easy to find analogues elsewhere) reminds us that today, when universities are under attack by activist billionaires and populist politicians, and the humanities are shrinking even on well-funded campuses, invocations of global history can play a strategic role. They help fend off mounting criticisms of historians’ supposed propensity to shy away from big questions and indulge in trivial details, to deny the knowability of truth, and give voice to the victims of past injustices in search of their (and their own) redemption (as the snarky blames go).

In the face of this rhetoric, global history has been a weapon of the weak. It projects a muscular quality (I use this gendered adjective purposefully) and evokes relevance for audiences within and beyond the academy. I am all for instrumentality—a laudable end justifies legitimate means. The question is why we are so reticent to be frank about our implicit intent. I presume that showing our cards would undermine our efforts, and I do not mean my ruminations to be self-defeating for the collective. But I also find that, in general, historians are not a particularly cynical or strategic bunch. If for once we are successful in our calculated schemes, we should find a way of leveraging global history in the interest of boosting enrollments and support for research without falling prey to it.

We can debate whether the fact that the impetus behind global history came from historians based in Europe and the United States is evidence that, for all its inconsistencies, it speaks to a collective aspiration to be more inclusive or is proof that it will never be able to shake off its unconscious biases and covertly imperialistic agenda. [18] In either case, we can agree that no institutional or pedagogical practice is ever neutral and disinterested. Sachsenmaier observes that ‘an increasing number of scholars in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and elsewhere have become convinced that much of human history is not best understood by containing our investigations within particular national or regional visions.’ That is true, but is he not grasping at something more than the benign and possibly welcome fact that ‘new forms of institutionalisation and interdisciplinary cooperation have started supporting historical research cutting across national and other boundaries’? [19] How egalitarian are these collaborations? To what extent do they emerge organically from shared intellectual pursuits and to what extent are they dictated by the desire to latch onto winning research agendas? Some specialists of non-Western regions and languages may feel compelled to reformulate their work under the guise of global history to making it more appealing, but at what cost?

An additional challenge associated with the institutionalisation of global history concerns the relationship between teaching and research. In the 1990s, world history carried with it a strong pedagogical impulse. One of the field’s chief promoters, Jerry Bentley, devoted considerable energy not only to sponsor world history in doctoral programmes and the historical profession at large but also to develop new content and standards for high school and undergraduate classes. [20] In some cases, notably the Global History Lab directed by Jeremy Adelman, a great deal of conceptualisation and financial commitments have gone into building innovative pedagogical programmes that reach beyond one’s own campus and seek to redress structural inequities. [21] But these are exceptions rather than the rule. The diversification of the student body is an important driver of curricular reforms, and faster in some countries than in others. Still few ‘new Italians’ are enrolled in college degrees in the humanities but it is cheaper to introduce global history at the undergraduate than graduate level. From anecdotal experience, in Italy the rush toward global history seems inspired by the need to catch up with granting institutions at home and abroad, even when the resources to train graduate students who might pursue wide-ranging and transnational projects are lacking.

Paradox no. 3: We cannot define global history but we debate its pros and cons

In the wake of Brexit, Richard Drayton and David Motadel wrote an ardent defense of global history as a means to combat Eurocentrism and xenophobia in the real world and the prominence of national history in all university systems. [22] By contrast, Giovanni Levi has denounced global history as yet another self-congratulatory instrument of Western imperialism. Its vagary, he writes, serves the devious purpose of demonstrating that ‘we in the West are best at world domination, best at self-criticism, and will soon be the best at producing a new and full-throated exaltation of global capitalism cleansed of its more shameful Eurocentric and nationalistic aspects.’ [23]

This is neither the first nor the last time that historians have disagreed, but are these scholars talking about the same thing? Obviously, I cannot speak for them but it seems fair to say that the three I just mentioned are not so far apart politically, at least in the great scheme of things. And yet they do not see eye to eye about the dangers and possibilities of whatever they refer to as global history. Is their opposite evaluation of global history a measure of divergent political opinions? That might be, but the differences in the works they discuss and the terms in which they do so make one wonder if some deeper confusion is not at play—a confusion that has been exacerbated rather than relieved by some clarifying attempts.

Paradox no. 4: We cannot define global history but we leverage a series of antinomies to debate its supposed pros and cons

Faced with the amorphous and elusive nature of global history, some authors have sought to fit it within strict interpretative grids hinging on familiar dichotomies (local vs global; micro vs macro; short vs long duration; case studies vs generalisations), when they have not also expressed their marked predilection for one or the other half of these oppositional terms.

Jo Guldi and David Armitage’s The History Manifesto is arguably the most egregious exhibit of this habit, if only because it muddles the waters by lumping together, on one side, all historical works that cover one episode or a few years and, on the other, all those that engage with long swaths of time. In light of this dubious contrast, Guldi and Armitage proceed to blame ‘the triumph of the short durée’ for nothing less than ‘the disintegration of the profession.’ [24] One may reasonably argue that The History Manifesto so caricatures historiographical trends that, a decade on, we can table it. [25] Its oversimplifications, however, expose the facility with which it is possible to mobilise global history for rhetorical purposes without having to account for its incongruities and complexities. Moreover, the book’s availability in open access makes it a go-to text for many readers across the globe who are priced out of scholarly literature in hard copy or behind digital paywalls.

In making the case for the novelty and potential of ‘transhistorical history,’ Guldi and Armitage maintain that ‘the attempt to transcend national history is now almost a cliché.’ [26] By stating so, they sidestep the need to examine it more closely. Meanwhile, they build their case against microhistory, which they fault for having ‘largely abandoned grand narrative or moral instruction in favour of focus on a particular event’ (readers are assumed to agree that abandoning moral instruction is a bad thing and that one cannot derive moral instruction from dissecting a single event—not even a colonial massacre?). [27]

An incidental sentence (a response to a reviewer’s comment?) in the middle of a long paragraph lamenting microhistory’s sentimental and antiquarian drift nevertheless concedes that ‘its method was […] not incompatible with temporal depth, as in a work such as Carlo Ginzburg’s study of the benandanti and the witches’ sabbath, which moved between historical scales of days and of millennia.’ [28] In support of their assertion, Guldi and Armitage cite Ginzburg’s Ecstasies. Curiously, they only refer to the Italian original, although Ecstasies was released in short order in English and French (two languages in which their readers would likely be more fluent). [29] Following Ginzburg’s conjectural paradigm, we can interpret this incidental sentence and the accompanying footnote as a ‘clue,’ or at least a Freudian lapsus that exposes the strawman quality of Guldi and Armitage’s thesis. [30]

Ecstasies is arguably a piece of global microhistory, except that it does not fit at all with how this genre has come to be defined. [31] Its protagonist is not an individual, a location or an event, but a cultural pattern that, according to Ginzburg, displays morphological similarities across the entire Eurasian continent for more than a millennium. The book has been faulted for being excessively ambitious and overgeneralising, certainly not for its narrow purview or aestheticising narrative. What matters here is that as he widened his lens from Friuli to Eurasia, Ginzburg did not shift his subject-matter but rather came to adjust his brand of microhistorical approach. [32] In other words, a global dimension was not Ginzburg’s goal as much as a means to test the outmost potential of his method. The point needs emphasising and I will return to it.

One can find other such clues in the manifold clumsy attempts to box global history into binary dichotomies, such as micro-macro, short-long, or local-global. An interview with Bayly published in Itinerario in 2007 is titled ‘I Am Not Going to Call Myself a Global Historian.’ The phrase catches one’s attention but distorts Bayly’s opinion. This is what he told his interviewer: ‘I have always remained a local historian and a regional historian as well as writing world history, and I am not going to call myself simply a “global historian”.’ [33] The elision of the word ‘simply’ voids the meaning of Bayly’s sentence, which insists on the complementarity rather than the opposition between local, regional, and global history. Omitting one word makes for a catchier title but generates the erroneous impression that global history may be something that replaced previous approaches.

Presumably because it is said to have become ‘a cliché,’ global history is given short shrift in The History Manifesto. Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence earns only a passing mention in a footnote as an example of the increasing attention that historians have paid to the environment. [34] Of course, The Great Divergence is that, but it is also much more. It is the rare book that is read by historians of all stripes, as well as by a good many humanists and social scientists. [35] It does not use the label of global history but it is also the rare title that, in a field without a canon, comes to mind consistently when speaking of global history. [36]

The Great Divergence provincialises the English industrial revolution by turning it into a contingent event rather than the inevitable culmination of a long period of incubation that supposedly set the European continent apart from most of the world beginning in the late Middle Ages or, at least, the sixteenth century. Pomeranz rejects this gradualist thesis and argues that, throughout the eighteenth century, the most advanced regions of China had standards of living comparable to those of England. The latter was propelled ahead not by its putatively superior ingenuity, better political and fiscal institutions, or growing secularisation. Only two factors mattered: the closer proximity of coal mines to manufacturing centres in England than in China and the cash-crop plantations cultivated by enslaved African men and women in the British Caribbean.

To say that Pomeranz’s thesis has not persuaded everyone is an understatement. But it has proven to be extremely generative, leading legions to engage with the ways in which the author arrived at it. Indeed, how Pomeranz argued his thesis has become as important as the thesis itself.

A few scholars embraced his method of ‘reciprocal comparisons’ but applied it to a number of variables that he had omitted, notably the state and its fiscal systems, military conquest, and the role of law in long-distance trade. [37] Mindful of the emphasis that Pomeranz places on British overseas colonies, some historians of China probed the expansion of Chinese public and private maritime activities to find that he overlooked their role. [38]

Among scholars of the English industrial revolution, The Great Divergence aligned with growing sensitivity toward questions of colonial exploitation and has stimulated new inquiries into the rippling effects of Caribbean slavery on the eighteenth-century British economy. [39] For the most part, however, economic historians have disputed Pomeranz’s thesis on the grounds that his numbers do not add up. Robert Allen and Stephen Broadberry are the names most closely associated with this line of refutation, but the outpouring of empirical studies with new datasets of prices and wages in Europe and Asia is nearly impossible to keep up with. [40] Taken together, this literature argues that England was the first region in the world to develop breakthrough labor-saving technology because labor was more expensive there than elsewhere while energy was cheaper.

This thesis, too, is highly contested, and by fellow economists to boot. There is no agreement among them on either the numerator or the denominator in the measurements of living standards. Allen’s samples of wages have been criticised for overrepresenting London, where wages were high, while the cotton industry took off in the north of England, and for overrepresenting adult men, who were significantly better compensated than women and children. [41] The estimates of population size and per capita GDP have come under equally trenchant scrutiny. [42]

In sum, there is no single quantitative approach to the study of the great divergence. Rather, this is a notable instance in which the broadening of our geographical scale of analysis has not only revived an old subject (why did England industrialise first?) but also ignited new and lively debates about how to approach it. Are macroeconomics and national accounting methods developed in the mid-twentieth century suitable to earlier epochs? Are the data at our disposal not only reliable but also commensurable? What do we factor into comparisons?

Conclusion: What We Study and How We Study It

We owe the earliest formulation of the law of diminishing returns to the French physiocrat Turgot in 1767, and further elaborations of it to David Ricardo and Thomas Malthus. [43] The law of diminishing returns, in other words, was conceived at a time when the environmental and technological constraints on productivity growth were severe and mortality crises recurrent, that is, long before mechanisation and fertilisers unleashed dreams of infinite growth. I doubt that historians are wiser than humanity at large, which still harbours dreams of growth in the face of the rapid, human-made depletion of the planet. But rather than making any forecasts about global history’s future rise or decline, I suggested that we analyse its present state of affairs. At a minimum, the law of diminishing returns requires that we know what the factors of production are, but do we know what global history is?

In 2004, Bayly wrote that ‘all historians are world historians now, though many have not yet realized it.’ [44]Today, we could rephrase this truism to say that all historians realise that we are now expected to be global historians. In the intervening twenty years, a new problem has come to the fore: what kind of a global historian does one wish to be? Unfortunately, this is not how the issue is usually framed. It is more common to come across discussions of whether global history is a panacea or a malady. The many state-of-the-field overviews that place global history at the end (for the time being) of a chronological sequence of historiographical currents have contributed to this fallacy.

On the occasion of her being awarded the Holberg International Memorial Prize in 2010, Natalie Zemon Davis seized onto the notion of ‘decentering history’ in order to articulate her life-long mission to shatter historiographical conventions. Looking back at her intellectual trajectory in relation to the evolution of the modes of writing European history that flourished during her long and distinguished career, she identified four ‘waves’ in the modalities that she and like-minded historians adopted to decentre history. A ‘first social way,’ which in the 1950s turned the attention away from elites and toward ordinary people, was followed by a ‘second social way’ that ‘starting in the 1960s brought women and gender to the fore.’ [45] Two geographical waves followed suit: the first erupted in response to questions ‘posed by the independence and postcolonial movements of the late twentieth century’; the second was prompted by the multiplication of nodal points and the increased interdependence of the world in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, although Davis hastens to note that ‘despite its commitment to multiple modernities, questions have been raised about the new global history—including by some of its own practitioners—about whether its historical agenda and categories are still just Western and Eurocentric.’ [46]

Needless to say, Davis pioneered or at least partook in and steered each of these four waves. She also preferred to write about the past than to assess the work of fellow historians. At least implicitly, however, she brings up the question I have tried to raise: what is the relationship between subject-matter and method? [47] A 2007 forum in the Journal of World History cited by Davis tackled the problem by asking three noted specialists to reflect on the intersection (or lack thereof) between social history, the history of women, gender and sexuality, and world history. [48] Each of these fields (if that is the right word) challenged the status quo; each decentred the scholarly ecology of the time. But they should not be regarded as part of a sequential evolution and are certainly not mutually exclusive.

Past & Present’s virtual special issue titled ‘Capitalism in Global History’ (2020) and its French counterpart, ‘Global History: The Annales and History on a World Scale’ (2014), are vivid reminders that the 1990s global turn did not happen in a vacuum and complemented rather than supplemented earlier approaches. [49] Assembled by two of the most established and prestigious academic journals for historians, these retrospective compilations demonstrate that concerns for the global dimensions of historical phenomena (especially though not exclusively in European history) were already robust in the 1950s. Moreover, both virtual issues display a great variety of approaches to the global among their chosen greatest-hits. In so doing, they foreground the point that I have been driving.

Put simply, global history can raise new questions, but does not prescribe or even suggest how to answer them; in fact, it is particularly malleable and amenable to a plurality of methodological perspectives and conceptual tools. Bayly got close to articulating this view when he wrote that global history ‘is a heuristic discipline which asks the question: What happens if we blow down the compartments which historians have made between this and that region, or between this subdiscipline of history and that one?’ [50] A ‘discipline,’ however, does more than raise new questions. In keeping with Ginzburg’s conjectural paradigm, the term here functions as yet another clue, in this case of the instability of all attempts at defining global history.

By accepting this instability as an essential feature of global history, we can begin to move beyond the paradoxes that grip much of our historiographical debate. Once we stop arguing over the supposed pros and cons of global history, we can also start discussing how the objects of our inquiries affect (or not) the ways in which we approach them.

As hinted at by Davis, a shift in subject-matter has often called for a retooling of historians’ presumptions. But a topic or a theme are not a method. When immediately after the Second World War Fernand Braudel urged us to study a region—the Mediterranean—rather than a royal dynasty or a nation-state, he did more than replace one object with another. Braudel’s undeniable Eurocentrism makes him a tainted forerunner of transregional and global history. In fact, whether those labels apply to him or not seems to me less important than to recognise that for Braudel, to study a geographical area required a new conceptualisation of time. His longue durée was not, pace Guldi and Armitage, the synonym of many centuries; it was a distinctively pre-industrial temporality in which climatic and environmental conditions placed enormous (though not insurmountable) constraints on human actions. Similarly, when Joan Scott made the case for gender as a category of analysis, she demonstrated that feminist historians could turn their initial interest in women into a conceptual tool to examine power structures involving both men and women. [51] This does not mean that since then, all histories of women or LGBTQ+ communities have mobilised gender as a category of analysis. Many were and are still principally aimed at rendering the experience of marginalised groups visible, in ways akin to Davis’ social waves. [52]

The tension between subject-matter and historical methodology is not new, but self-described global historians hide it more often than not. Arguing for the potential of integrating global history and gender history, Dana Paton calls the former ‘a methodology that follows connections through time and across distance in order better to understand historical development at different spatial scales.’ [53] By now it should be clear why I beg to differ and do not find it helpful to consider global history ‘a methodology.’ Most importantly, Paton’s own argument corroborates my point. She summarises her thesis as follows:

a principal reason that Atlantic slavery could expand so far and so fast was that it built on existing European patriarchal systems that divided women into categories: the virtuous, who could marry and be a conduit for the transmission of property; and those whose childbearing outside of legitimate marriage did not enable the transfer of property. [54]

We infer that global history provided Paton with a new question concerning ‘the social reproduction of the Atlantic slavery system’ but it was gender as a category of analysis that led her to her answers. Global history, as Paton notes, has accelerated the move of colonial extraction and exploitation from the margins to the mainstream of the profession. It has also left historians free to tackle those issues from a variety of approaches.

In the end, as you have gathered, my goal is not to arrive at a fuller and more precise definition of global history. Quite the opposite: my premise is also my conclusion. Global history’s lack of consistency is not a problem we need to solve, let alone make go away. It is a measure of our times, with which we need to contend in order to map some of the tectonic shifts that are remaking our academic worlds. Global history is everywhere. We grasp intuitively what it means, but cannot pin it down. We may wish to deploy it for strategic reasons linked to our collective survival. But we should not confuse the ends with the means. Only by scaling back the status of global history, by recognising that it is a lever rather than a precision tool, that it raises new questions but neither stipulates nor recommends how to go about answering them, can we harness its potential. This is the ultimate paradox: only by making global history smaller will its payoffs become bigger. What matters is how we do global history rather than whether we do it or not.

[1] This piece is a revised version of the Bayly Memorial Lecture that I delivered at St. Catharine’s College, the University of Cambridge, on 24 November 2023. Its aim, as well as the nature of the occasion, mean that the works cited are highly selective, but hopefully apt to signpost broader trends. From its inception, I have had in mind several of the spirited interventions in this Forum, to which these pages are a partial response.

[2] ‘Perhaps the “global turn,” for all of its insights and instruction, has hit a point of diminishing returns. The fact that contemporary technology, economics, and politics have made us so acutely aware of global connections in our own day does not mean that past events are always best dealt with by setting them within a similarly vast context.’ David A. Bell, ‘This Is What Happens When Historians Overuse the Idea of the Network,’ The New Republic, 26 October 2013, https://newrepublic.com/article/114709/world-connecting-reviewed-historians-overuse-network-metaphor. See also an online discussion that this article ensued: https://imperialglobalexeter.com/2013/11/26/diminishing-returns-of-the-global-turn/, accessed 4 February 2024. In 2016, the annual meeting of the American Historical Association hosted a panel titled ‘Diminishing Returns of a Turn? Transnational and Global History, 10 Years On’: https://aha.confex.com/aha/2016/

webprogram/Paper19670.html, accessed 4 February 2024.

[3] Nora Berend, ‘Interconnection and Separation: Medieval Perspectives on the Modern Problem of the “Global Middle Ages”,’ Medieval Encounters 29, nos 2–3 (2023): 285–314.

[4] Jeremy Adelman, ‘What is Global History Now?’ Aeon, 2 March 2017, https://aeon.co/essays/is-global-history-still-possible-or-has-it-had-its-moment.

[5] C.A. Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 1780–1914: Global Connections and Comparisons (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004). There is now, for example, a flourishing historical literature on populism and economic nationalism in the post-colonial world. See, e.g., Aditya Balasubramanian, ‘A More Indian Path to Prosperity? Hindu Nationalism and Development in the Mid-Twentieth Century and Beyond,’ Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics 3, no. 2 (2022): 333–78.

[6] Sebastian Conrad, What Is Global History? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016). The author lists the following translations on his webpage: Chinese; Taiwanese; Spanish; Russian; Estonian; Portuguese; Japanese; Turkish and Serbian under contract. https://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/e/fmi/institut/mitglieder/Professorinnen_und_Professoren/conrad.html, accessed 4 February 2024. The list is incomplete, if only because it omits the Italian edition, which in 2022 was in its sixth edition: https://www.carocci.it/prodotto/storia-globale, accessed 4 February 2024.

[7] ‘Prof. Dominic Sachsenmaier,’ Global and Transregional Studies Platform Goettingen, https://gts-goettingen.de/project/prof-dr-dominic-sachsenmaier/, accessed 4 February 2024.

[8] Dominic Sachsenmaier, ‘Global history,’ Version 1.0, Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 11 February 2010,http://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.2.588.v1.

[9] More could be said about the notion of ‘methodological nationalism,’ especially in relation to areas of historical inquiry that concern the periods before 1800. The expression is usually traced back to scholars of modern migratory movements: e.g., Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glick Schiller, ‘Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-state Building, Migration and the Social Sciences,’ Global Networks 2, no. 4 (2002) 301–34; Wimmer and Schiller, ‘Methodological Nationalism, the Social Sciences, and the Study of Migration: An Essay in Historical Epistemology,’ The International Migration Review 37, no. 3 (2003): 576–610.

[10] Lynn Hunt, Writing History in the Global Era (New York: Norton, 2014), 13. One of the strengths of Hunt’s account is that it links changes in historiography and society at large. In this respect, it reflects trends prevailing in the United States more than elsewhere.

[11] See the forum ‘Historiographic “Turns” in Critical Perspective,’ The American Historical Review 117, no. 3 (2012): 698–813. In a recent conference program, I spotted the term ‘semi-disciplines,’ which I had not encountered before: https://networks.h-net.org/system/files/attachments/othernarrativesearlyislamposter24.pdf, accessed 29 February 2024.

[12] Niall Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (New York: Basic Books, 2004); Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Knopf, 2014).

[13] I borrow the expression from Kevin Bales, Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy, 3rd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

[14] The EUI Global History Seminar Group, ‘For a Fair(er) Global History,’ Cromohs: Cyber Review of Modern Historiography (2021), https://doi.org/10.36253/cromohs-12559. The names of twenty-one authors are listed alphabetically, with no distinction between teachers and students, but with the indication of everyone’s nationality (or, in one case, nationalities).

[15] ‘The Series of Dialogues on Global History’ was recorded in 2021 and features, in order of appearance, Masashi Haneda (The University of Tokyo, host), Alessandro Stanziani (EHESS, Paris), Sheldon Garon (Princeton University), Maxine Berg (University of Warwick), Antonella Romano (EHESS, Paris), Jeremy Adelman (Princeton University), Sebastian Conrad (Berlin Free University), Lisa Hellman (University of Bonn), Andrea Eckert (Berlin Humboldt University), Marc Elie (CNRS, Paris), and Ge Zhaoguang (Fudan University): https://www.tc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ai1ec_event/3134/, accessed 4 February 2024.

[16] ‘MPhil in World History,’ University of Cambridge Postgraduate Study, https://www.postgraduate.study.cam.ac.uk/courses/directory/hihimpwhs, accessed 4 February 2024; ‘Global and International History,’ Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/series/global-and-international-history/A7B42D0DEF99BBEB10B5566D6328CF2C, accessed 4 February 2024.

[17] ‘Global Cambridge,’ University of Cambridge, https://www.cam.ac.uk/a-global-university, accessed 4 February 2024.

[18] For a particularly insightful and learned treatment of what is colloquially called ‘positionality’ (a term not used by the author), see Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Aux origines de l’histoire globale (Paris: Collège de France, 2014).

[19] Dominic Sachsenmaier, Global Perspectives on Global History: Theories and Approaches in a Connected World(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 2–3.

[20] Jerry H. Bentley is, among other things, the co-author of a college-level textbook that is presently in its sixth edition, Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past (Boston: McGraw Hill, 2000), https://www.mheducation.com/prek-12/program/bentle

y-traditions-encounters-global-perspective-past-updated-6e-ap-edition-2017/MKTSP-GEO09M0.html, accessed 4 February 2024.

[21] ‘Global History Lab,’ CRASSH, University of Cambridge, https://www.crassh.cam.ac.uk/research/projects-centres/global-history-lab/, accessed 4 February 2024.

[22] Richard Drayton and David Motadel, ‘Discussion: The Futures of Global History,’ Journal of Global History 13, no. 1 (2018): 1–21, which is a rejoinder to two widely-read pieces: Bell, ‘This Is What Happens When Historians Overuse the Idea of the Network,’ and Jeremy Adelman, ‘What is Global History Now?’.

[23] Giovanni Levi, ‘Frail Frontiers?’ Past & Present 242, supplement 14 (2019): 37–49 (42–43).

[24] Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 54. I cite the authors in the order in which their names appear on the book cover.

[25] Deborah Cohen and Peter Mandler, ‘The History Manifesto: A Critique,’ The American Historical Review 120, no. 2 (2015): 530–42; Francesca Trivellato, ‘A New Battle for History in the Twenty-First Century?’ Annales: Histoire, Sciences Sociales 70, no. 2 (2015): 261–70.

[26] Guldi and Armitage, The History Manifesto, 15.

[27] Guldi and Armitage, The History Manifesto, 45–46.

[28] Guldi and Armitage, The History Manifesto, 46.

[29] ‘Carlo Ginzburg, Storia notturna. Una decifrazione del sabba (Turin, 1989).’ Guldi and Armitage, The History Manifesto, 136, note 22. See also Ginzburg, Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath, Eng. trans. RaymondRosenthal (New York: Pantheon Books, 1991).

[30] Carlo Ginzburg, Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method, Eng. trans. John and Anne C. Tedeschi (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), esp. 96–125.

[31] Tonio Andrade, ‘A Chinese Farmer, Two Black Boys, and a Warlord: Towards a Global Microhistory,’ The Journal of World History 21, no. 4 (2011): 573–91; John-Paul Ghobrial, ed., ‘Global History and Microhistory,’ Past & Present242, Supplement 14 (2019).

[32] See also Carlo Ginzburg and Bruce Lincoln, Old Thiess, a Livonian Werewolf: A Classic Case in Comparative Perspective (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020).

[33] Binu M. John, ‘“I Am Not Going to Call Myself a Global Historian.” An Interview with C.A. Bayly,’ Itinerario 31, no. 1 (2007): 7–14 (12) (my emphasis). See also C.A. Bayly, ‘Introduction,’ in The C.A. Bayly Omnibus (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009), xiii. Contrast with Martine van Ittersum and Jaap Jacobs, ‘Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage,’ Itinerario 36, no. 2 (2012): 7–28, esp. 25.

[34] In fact, The Great Divergence is only mentioned in the original version of the book, published in 2014: Guldi and Armitage, The History Manifesto, 144, note 30, where Pomeranz is cited alongside Fredrick Albritton Jonsson, Enlightenment’s Frontier: The Scottish Highlands and the Origins of Environmentalism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). The revised and corrected 2017 edition replaced Pomeranz with James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998) in the same footnote. Because both editions of The History Manifesto are accessible in open access, it is not always easy to determine which one of the two one is reading or someone is citing.

[35] For an example of the engagement from post-colonial studies, see Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘Can Political Economy Be Postcolonial? A Note,’ in Postcolonial Economies, eds Jane Pollard, Cheryl McEwan, and Alex Hughes (London: Zed Books, 2011), 23–35; reprinted in Chakrabarty, The Crises of Civilizations: Exploring Global and Planetary Histories(New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018), 16–27.

[36] It tops the list of ‘Best Books in Global History’ by Maxine Berg, founding director of Warwick’s Global History and Culture Centre, established in 2007 (the first of its kind in the United Kingdom): https://fivebooks.com/best-books/global-history-maxine-berg/, accessed 4 February 2024. Another example is the discussion of Pomeranz’s The Great Divergencein Sarah Maza, Thinking About History (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 75–77.

[37] Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and R. Bin Wong, Before and Beyond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[38] Melissa Macauley, Distant Shores: Colonial Encounters on China’s Maritime Frontier (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021); Ronald C. Po, ‘Qing China and Its Offshore Islands in the Long Eighteenth Century,’ The Historical Journal (2024): 1–33 (first view).

[39] Gavin Wright, ‘Slavery and Anglo-American Capitalism Revised,’ The Economic History Review 73, no. 2 (2020): 353–83; Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson, Slavery, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution (London: Polity Press, 2023).

[40] Robert C. Allen, ‘The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War,’ Explorations in Economic History 38, no. 4 (2001): 411–47; Stephen Broadberry, ‘Historical National Accounting and Dating the Great Divergence,’ Journal of Global History 16, no. 2 (2021): 286–93.

[41] Pat Hudson’s review of Robert C. Allen, The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), in The Economic History Review 63, no. 1 (2019): 242–45, esp. 244; Jane Humphries, ‘The Lure of Aggregates and the Pitfalls of the Patriarchal Perspective: A Critique of the High Wage Economy Interpretation of the British Industrial Revolution,’ The Economic History Review 66, no. 3 (2013): 693–714.

[42] Timothy W. Guinnane, ‘We Do Not Know the Population of Every Country in the World for the Past Two Thousand Years,’ The Journal of Economic History 83, no. 3 (2023): 912–38.

[43] Stanley L. Brue, ‘Retrospective: The Law of Diminishing Returns,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 7, no. 3 (1993): 185–92.

[44] Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 469.

[45] Natalie Zemon Davis, ‘Decentering History: Local Stories and Cultural Crossing in Global World,’ History and Theory 50, no. 2 (2011): 188–202 (190).

[46] Davis, ‘Decentering History,’ 190–91.

[47] ‘Decentering involves the stance and the subject-matter of the historian. The decentering historian does not tell the story of the past only from the vantage point of a single part of the world or of powerful elites, but rather widens his or her scope, socially and geographically, and introduces plural voices into the account.’ Davis, ‘Decentering History,’ 190.

[48] Peter Stearns, Merry Wiesner-Hanks, and Kenneth Pomeranz, ‘Forum: Social History, Women’s History, and World History,’ Journal of World History 18, no. 1 (2007): 43–98. See also Giorgio Riello, ‘The “Material Turn” in World and Global History,’ Journal of World History 33, no. 2 (2022): 193–232.

[49] Andrew D. Edwards, Peter Hill, and Juan Neves-Sarriegui, eds, Capitalism in Global History, virtual issue, Past & Present (2020), https://academic.oup.com/past/pages/capitalism-in-global-history?login=true, accessed 4 Febraury 2024; Étienne Anheim, Romain Bertrand, Antoine Lilti, and Stephen Sawyer, eds, Global History. The Annales and History on a World Scale, parcours historiographiques, Annales. Histoire, sciences sociales (2014), http://annales.ehess.fr/index.php?252, accessed on 4 February 2024.

[50] Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 469 (my emphasis).

[51] Joan W. Scott, ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,’ The American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1053–75.

[52] Social history looms large on a classic in gay history such as George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994).

[53] Diana Paton, ‘Gender History, Global History, and Atlantic Slavery: On Racial Capitalism and Social Reproduction,’ The American Historical Review 127, no. 2 (2022): 726–54 (727). []

[54] Paton, ‘Gender History,’ 727.