The Fabric of the World: Clothing, Vision, and the Making of Global Difference

GIOVANNI TARANTINO

University of Florence

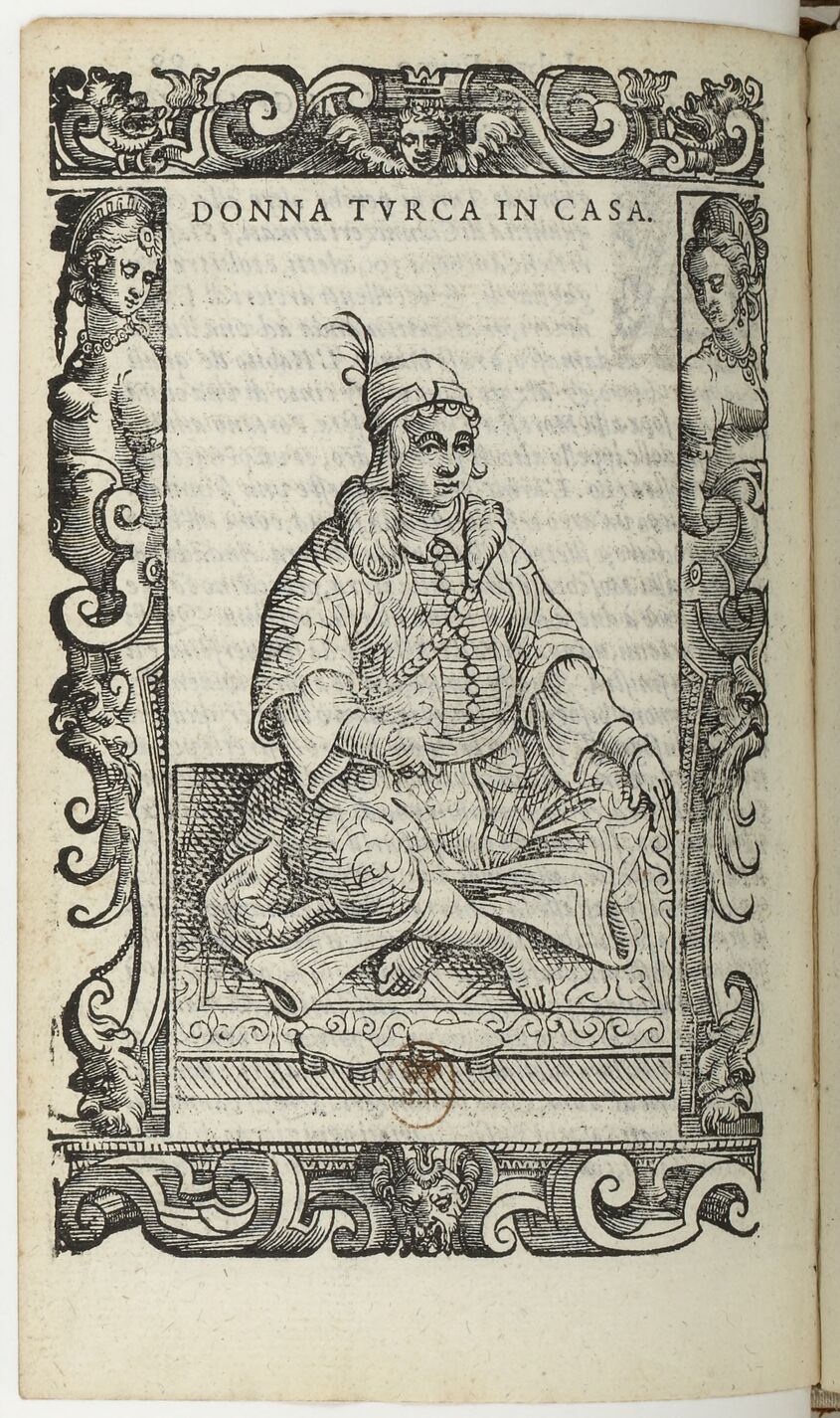

Cesare Vecellio, Donna Turca in Casa, from De gli habiti antichi, e moderni di diverse parti del mondo libri due (Venice: presso Damian Zenaro, 1590), Bibliothèque nationale de France, RESERVE OB-12-4, 388v. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica. https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb403566709

Giulia Calvi’s Vestire il mondo is a genuine gem: an original, finely crafted work built on a deep and meticulous knowledge of its sources—some unpublished, others rarely studied—and enhanced by a visually and conceptually rich corpus of illustrations. Many of these images, discussed or reproduced here for the first time, enable readers to reconstruct visual genealogies of great significance and to reinterpret the dynamics of representation and the domestication of otherness that accompanied the first phase of globalisation.

The chronological span of Calvi’s study is broad, extending from the second half of the sixteenth century to the publication in Tokyo in 1801 of The Book of Costumes by Yamamura Saisuke. The book thus traces an arc that traverses the formative centuries of European colonial empires and the construction of a global imaginary. Published by il Mulino, Vestire il mondo expands and deepens the reflections that Calvi first articulated in her 2022 contribution to Cambridge University Press’s Elements in the Renaissance series, situating them within a more expansive and comparative framework—most notably in Chapters I and III, and in the corresponding iconographic apparatuses, which are absent from the English edition.

At first sight, the topic might appear rather specialised: the so-called books of costumes, illustrated collections depicting forms of dress from Europe and beyond during the early modern period. Yet, as Calvi demonstrates with remarkable acuity, these works were anything but marginal. They were part of the broader intellectual and visual fabric of their time—simultaneously tools for classification, media of representation, and stages on which identities and cultural differences were displayed and interpreted.

To understand their importance, one must situate them within the cultural environment that gave rise to them. The sixteenth century was, as Anthony Grafton has written, a period of genuine ‘information explosion’: the press multiplied the circulation of books, maps, atlases, and illustrated chronicles. [1] The expansion of the known world—through encounters with the peoples of the Americas, the Ottoman Empire, and the diplomatic and missionary exchanges with Asia—demanded new modes of knowing, describing, and representing human diversity.

How could one convey, to a European audience fascinated by novelty, the variety of societies and cultures discovered at the world’s edges? Dress provided one of the most effective answers. Clothing was visible, immediate, and infinitely variable. Unlike language, it required no translation; unlike religion, it demanded no theological mediation. It could be apprehended at a glance.

As Calvi notes, these books of costumes inaugurated ‘a visual culture of difference’. They presented readers with sequences of human figures arranged by geography, religion, or social rank, each recognisable through attire. Clothing thus became a direct language of identity. The robe of a Venetian merchant, the fur of a Polish nobleman, or the turban of an Ottoman dignitary—all operated as visual signs in a grand taxonomy of humankind.

At the same time, the production of costume books intersected with other areas of knowledge. Maps of the period were frequently adorned with figures in regional dress positioned at the margins of continents; chorographies—the descriptive accounts of lands and peoples—included details of local attire. One need only think of Olaus Magnus’s Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Rome, 1555), a monumental portrayal of the peoples of the North, illustrated with images of fishermen, reindeer hunters, and Sámi communities wrapped in their characteristic furs. These images did not simply accompany the text; they constructed a new way of seeing—a world visually ordered through the lens of clothing.

Venice, as a crossroads of cultures and a powerhouse of Renaissance print, became the pivotal centre of this visual production. From there, costume books spread to France, the German territories, and across the continent. They were translated, adapted, and copied; the same images circulated from one publication to another, sometimes faithfully reproduced, at other times subtly modified—a sign of the remarkable mobility of the visual language of costume. Calvi stresses that this mobility makes the costume books truly transnational works, in which visual knowledge was not the property of a single author or place but was continually redefined through circulation.

This diffusion also reveals the porous boundaries between erudition, art, and commerce. Costume books were purchased by scholars, diplomats, and artisans, but also by an educated and curious public who perceived in them a pictorial atlas of the world. They could serve as repertories for tailors or scenographers, as sources for geographers and chroniclers, or as aesthetic objects of conversation in courts and salons. In short, they were visual archives of possibilities—tools of knowledge, but also of delight.

Calvi opens her analysis at the very heart of Europe, where the genre first took shape. From the mid-sixteenth century onwards, artists and printers produced flourishing collections of habiti—as they were known—that documented the ancient and modern fashions of the known world. Among the most celebrated is Cesare Vecellio’s Degli habiti antichi, et moderni di diverse parti del mondo, first published in Venice in 1590. Vecellio, a cousin of Titian, gathered hundreds of woodcuts depicting men and women from diverse regions, each accompanied by a brief descriptive text.

The project was ambitious, almost encyclopaedic: to offer a visual map of humanity parallel to the cartographic mapping of the globe. The first edition contained 428 figures; the second, published in 1598 (Habiti antichi et moderni tutto il mondo), expanded to 503 and appeared in both Italian and Latin for an international audience. In these pages, Vecellio constructed a figurative geography of the inhabited world in which the Earth no longer appeared as an empty expanse surrounding Europe, but as a populated whole, dense with human difference.

Even the proportions of the book reflect Europe’s centrality and self-representation. Of the 339 European figures in the first edition, 202 are female and 137 male—a markedly feminised Europe. By contrast, the section devoted to the Turks comprises thirty-two images, twenty-five of them male, mostly religious or military figures. The limited access of Western observers to Muslim women translates into a scarcity of female portraits, often imbued with subtle eroticism—bare feet, crouching poses, trousers that reveal more than they conceal.

This asymmetry reappears elsewhere: the East is once again feminised, while Africa and the Americas are portrayed largely through naked or armed male bodies. As Calvi observes, Vecellio’s Habiti blend antiquarianism and ethnography: the study of the past and the description of the present converge in a comparative investigation of cultures. The ‘customs of living peoples’, she writes, ‘become keys to understanding ancient civilisations’, and vice versa.

In both editions of Cesare Vecellio’s Habiti (1590 and 1598), an intricate process of selection and re-elaboration brought together images that had previously illustrated some of the sixteenth century’s most successful European publications. Among the authors from whom Vecellio drew were Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Olaus Magnus, Nicolas de Nicolay, Juan González de Mendoza, and Theodor de Bry—geographers, travellers, and chroniclers who had shaped the visual imagination of alterity.

Calvi shows how, through this act of synthesis, Vecellio transformed a heterogeneous visual archive into a coherent repertory in which clothing became the organising principle of the world’s order. Yet, as she cautions, the result is far from neutral. Its iconographic and narrative choices carry implicit hierarchies and moral judgements. European attire is presented as harmonious and elegant, whereas the garments of others appear exoticised or distorted, at times morally ambiguous.

Gender plays a decisive role in this visual taxonomy. Female figures are grouped according to a moral and domestic typology—maidens, brides, mothers, widows, or servants—while men are distinguished by social position, occupation, or public role. Difference of gender thus becomes a means to express civic and moral hierarchies. Religion, too, is translated into image through dress: clerics and monastics are set apart from Jewish or Muslim figures. In this way, costume books emerge as veritable visual theologies that transform diversity into sign, organising it into an immediately legible yet profoundly ideological language. As Calvi succinctly puts it, ‘difference is staged, not simply recorded’.

The very word habito—from the Latin habitus—encapsulates a double meaning: both ‘appearance’ and ‘demeanour’. It signifies not only the act of dressing but also posture, bearing, and even nakedness. Hence the inclusion of semi-nude or unclothed non-European bodies—images that fix otherness within a hierarchy of appearances. Calvi identifies here one of the book’s most compelling interpretative cores: costume books participate in the formation of a new visual regime in early modern Europe. Responding to the expansion of geographical and cognitive horizons, they offered an ordered and at once hierarchical gallery of human diversity. Operating, in her words, ‘between art and science’, these images aspire to documentary and ethnographic authority. They are not mere curiosities but instruments of knowledge—and of power.

Between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries, this visual literature spread beyond Europe to the Near and Far East. Calvi analyses these movements of exchange and decentring with exceptional sensitivity. Her perspective shifts the focus of the Italian and European Renaissance, bringing to light a range of lesser-known authors, geographers, and printers whose works challenge the Western monopoly of the visual discourse. Costume books, she reminds us, were not only made about others but also produced by others. Many record the attire of ethnic, linguistic, or religious minorities and stand as precious witnesses of resistance to internal and external forms of colonisation.

In colonial contexts, clothing and luxury served to mark social distinction and to stabilise hierarchies. The display of splendour—regardless of skin colour, which had not yet become a fixed marker of civilisation—signified membership of the elite and reinforced the distance between clothed and naked bodies, between dominators and dominated. As Peter Burke has observed, early modern societies were acutely aware of dress as a visible indicator of rank and belonging. Sumptuary laws, which regulated the use of fabrics and ornaments, translated social order into visible hierarchy. When costume books depicted a Venetian noblewoman in silk or a German merchant in more modest garb, they did not merely describe reality: they codified and reaffirmed it. [2]

Similarly, when they looked beyond Europe, societies were judged through their costumes. The sumptuous fabrics of Ottoman dignitaries could elicit admiration but were simultaneously interpreted as signs of excess, opposed to the supposed moderation of Christian attire. In this way, costume books both reflected and shaped an aesthetic and moral order.

The opening chapter of Calvi’s volume, aptly titled ‘Hierarchies of Continents and Peoples’, lays the groundwork for what follows. She demonstrates how these works aligned with other classificatory tools of early modern knowledge—atlases, encyclopaedias, emblem books, cabinets of curiosities—all engaged in the same effort to render the world’s variety legible. Yet, unlike those textual compilations, costume books combined scientific ambition with theatricality. Their figures are posed, idealised, and stylised, standing before the reader as if on stage. The world, quite literally, is performed through dress, rendered by garments that are simultaneously real and symbolic.

The analogy with Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarum (Antwerp, 1570), the first modern atlas, is deliberate. Its frontispiece presents five female figures personifying the continents, ordered hierarchically by their clothing, posture, and complexion. America, dark-skinned and semi-nude, appears the most ‘wild’, while the still-unknown Terra Australis lacks a body altogether. This feminised iconography of the continents would enjoy a long fortune, reflecting both the idealisation of European virtue and the perceived availability—and vulnerability—of other continents to conquest and domestication.

It is therefore unsurprising that Ortelius’s compositional model found numerous echoes in later costume books. Vecellio’s Habiti similarly oppose a clothed and civilised Europe to a bare, ‘natural’ Africa and America. In the 1598 edition, Calvi notes, Europe is crowned and given a sceptre, visual emblems of a now-consolidated symbolic hegemony. Costume books thus perform a double function: they gather and organise knowledge about human societies while at the same time affirming European identity. They embody, with striking clarity, the tensions of early modernity—the desire to know the world and the determination to remain at its centre.

In the subsequent chapters, Calvi’s narrative moves beyond the Mediterranean towards Scandinavia, the Ottoman Empire, and Japan. In each case, Vecellio’s books provide a necessary point of departure, but Calvi extends her analysis to a plurality of authors, local artistic forms, and hybridising processes that redefine the Renaissance tradition of the costume book.

If Vecellio had devoted little space to Sweden and the Baltic in his first edition, his second greatly widened the horizon, including the entire Scandinavian peninsula and its inhabitants. He described them, borrowing an expression from Giovanni Botero’s Relazioni universali, as ‘the new world within Europe’. The phrase reveals a telling geographical imagination: the Arctic, largely unknown and absent from ancient sources, was perceived as a kind of internal elsewhere—a region both European and alien, rendered mysterious by its icy light and remoteness.

The richest and most imaginative encyclopaedic account of the northern peoples was Olaus Magnus’s 1555 Historia, written in exile and combining moral, religious, and ethnographic motives. Vecellio drew extensively on Magnus, especially for the second edition of his Habiti, but stripped the images of their original visionary charge, domesticating their strangeness. The Laplanders’ wildness is softened into picturesque curiosity: an instance of what Calvi calls ‘internal exoticism’, transforming the far North into a theatre of difference that is at once familiar and remote.

A particularly significant aspect, highlighted by Calvi, concerns the representation of women. In both Magnus and Vecellio, female figures play a prominent role—hunting, sleeping in tents, sharing men’s labour and fatigue. This vision, which reflects the relative gender fluidity of Arctic societies, is nonetheless reframed through the lens of Christian moralism. Magnus and Vecellio alike oppose the supposed ‘promiscuity’ of northern customs to the Christian ideal of woman as wife and mother, emblem of domestic order and virtue. The Renaissance North thus appears as an ‘internal other’, a moral geography through which southern Europe defined its own civility.

The third chapter of Calvi’s volume, appropriately titled ‘Internal Boundaries and Minorities’, opens with a particularly fascinating testimony: that of Andrea Navagero, Venetian ambassador to Spain, who in 1526 travelled with the convoy accompanying Charles V through his newly unified Iberian realms. Navagero’s diary, written during the journey, vividly evokes a Spain profoundly transformed—a land partly depopulated by the migration of men to the American colonies, yet also marked by sharp ethnic, religious, and cultural tensions.

Navagero’s observations intersect with the drawings and watercolours of Christoph Weiditz, the German artist who, during the same years, produced an exceptional Trachtenbuch—a ‘book of costumes’ now preserved in Nuremberg. Weiditz’s work, based on direct observation during his stay in Spain with the imperial entourage, offers an invaluable record of the peninsula’s social and cultural variety at that critical moment.

Both Navagero and Weiditz document the visible presence of minorities of Islamic origin in southern Spain—the Moriscos—through depictions of their daily practices, clothing, crafts, and ceremonies. In these images, dress becomes the tangible mark of a difference that persists. The fabrics, colours, and hairstyles signify a cultural fidelity that survives forced conversion and therefore continues to arouse suspicion.

At the same time, Weiditz’s drawings register the appearance of new subjects: young people from the West Indies. Dark-skinned and half-naked, they are portrayed in poses suggesting a progressive ‘civilising’ process—an ongoing westernisation. Calvi insightfully reads these figures as expressions of the intertwining of conquest, enslavement, and spectacle: the colonial body displayed as visual commodity, the living image of an elsewhere both conquered and disciplined.

The Moorish women of Granada, represented by Weiditz and later reinterpreted by Vecellio, form a striking case of visual transformation. In the Venetian engravings they appear detached from their original context, stripped of everyday setting and temporality. Uprooted from history, they become images of timeless difference, serving to reinforce the notion of an irreducible cultural gap. Dress, which in its context had signified belonging and identity, becomes here a mark of otherness—a visual shorthand for non-assimilation.

Yet, as Calvi demonstrates, clothing can also act as disguise. Particularly interesting is the case of women belonging to the Mozarabic Christian communities—those who lived under Muslim rule in Andalusia without converting. In a society shaped by coexistence and mistrust, daily proximity among old Christians, new Christians (converted Muslims), and Mozarabic Christians produced forms of hybridisation in clothing. Muslim women appeared in public tapadas, partially veiled, but Mozarabic women sometimes adopted the same attire to blend in or to escape religious identification. They, in Calvi’s words, ‘undressed themselves of their Christianity in order not to be seen’. Dress thus ceased to mark a fixed frontier of identity and became a medium of crossing and ambiguity—a space of negotiation between cultures.

Through this play of veiling and imitation, Spain’s ‘internal Orient’ emerges as a visual laboratory of difference. Alterity is no longer purely external—Turkish, African, or American—but internal, rooted within the heart of Europe itself. Through clothing and its representation, costume books do not simply record; they construct a moral geography of the visible, distinguishing those who belong from those who remain excluded, even when they share the same space.

In stark contrast to the image of the women of the South—portrayed as secluded, sensual, or indolent, legacies of the long Islamic presence—the North of Spain is depicted as the realm of female industriousness. Costume books linger over these contrasting figures, portraying the women of Biscay with their shorn heads and uncovered faces as strong, dignified, and hardworking, often engaged in everyday labour. In Vecellio and his contemporaries, Spain’s female geography appears deeply divided: in the South, veiled women, symbols of sensuality and submission; in the North, unveiled women, embodiments of vigour and virtue. Yet even this energetic femininity could be read ambivalently—as disruptive, demonic, and requiring containment from above.

For the section devoted to the Levant, Calvi turns to an extraordinary and previously unstudied source: the watercolour drawings of Cristoforo Roncalli, known as il Pomarancio, produced during his 1606 journey accompanying the Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani through northern Europe. The second part of Roncalli’s album—a remarkable collection of fifty-seven watercolours—depicts male and female costumes representing the political, social, and religious hierarchies of the Ottoman Empire. These figures, executed at Giustiniani’s commission (his family having long governed the Aegean island of Chios before its Ottoman conquest), were not drawn from direct observation but from a sophisticated visual mediation.

Roncalli drew inspiration from Nicolas de Nicolay’s Navigationi et viaggi (Venezia, 1580; first French edition: Lyon, 1567), a seminal work that devoted extensive attention to the Christian minorities of the Ottoman world. As Calvi shows, Nicolay’s engravings played a decisive role in shaping Western representations of the Ottoman Empire—detailed yet theatrical depictions that crystallised an image of a multi-ethnic and multi-religious polity, at once orderly, exotic, and hierarchically composed. Many of the ‘Turkish costumes’ reproduced by Vecellio derived directly or indirectly from Nicolay’s models. Calvi reads Roncalli’s corpus, through the dual mediation of Nicolay and Giustiniani, as a revealing example of the transmedial circulation of Ottoman imagery in early modern Europe: a demonstration of how visual motifs travelled, were reworked, and adapted to new cultural contexts.

Turning to the Balkans—a region of particular Venetian interest and one that Vecellio perceived as within his own cultural orbit—representing clothing meant situating ethnic, linguistic, and religious communities within a broader political frame defined by imperial rivalry. In this borderland, clothing functioned as a fluid and ambivalent sign: a language through which affiliations were negotiated and differences disguised. Bodies, and particularly women’s bodies, became surfaces of cultural translation, sites where multiple identities overlapped and intermingled. Female attire—veils, fabrics, jewellery—was never merely decorative but an instrument of recognition and disguise, a visual device of belonging and resistance.

In these Balkan territories, where Ottoman, Venetian, and Habsburg influences intertwined, clothing narrated a complex political geography—a mosaic of intersecting loyalties, mutable frontiers, and power relations expressed through the visible. Vecellio’s woodcuts translate this complexity into image but simultaneously simplify it, ordering it within a European logic of classification that sought to fix what, in reality, was fluid and unstable.

Calvi devotes an entire chapter to the Ottoman world, where the relationship between dress and representation becomes even more revealing. The Ottomans, she reminds us, were not merely the objects of European observation but also active producers of images, fully participating in this shared visual culture of identity, difference, and classification.

We are accustomed to viewing the Ottoman Empire through the lens of conflict—Vienna, Venice, Lepanto—yet the relationship was far more intricate. Alongside military rivalry existed a dense intellectual and artistic exchange. The frontier between Europe and the Ottoman world was porous and vibrant, traversed daily by merchants, ambassadors, and artists. Costume images travelled these routes: European engravings reached Istanbul, while Ottoman albums journeyed westwards. Styles and motifs crossed and mingled, giving rise to new hybrid forms.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Ottoman albums, Calvi notes, lies in their dual purpose. On the one hand, they served as visual registers of the empire’s social order. Miniaturists depicted officials of every rank, soldiers, guild members, and women of different classes, all distinguished by dress. These albums could be presented to the sultan or high dignitaries as reminders of imperial hierarchy—mirrors of society. On the other hand, many were made for foreign audiences—ambassadors, merchants, collectors—eager to possess a visual souvenir of the empire. For them, the albums offered carefully constructed portrayals of Ottoman splendour and order.

The cover image of Calvi’s volume captures this perfectly: a bride from a costume album produced in Constantinople in 1657–1658, commissioned by the Swedish ambassador to the Ottoman court. Many such albums were later reassembled in Europe, annotated and adapted to Western tastes—as shown by an example now held in Florence’s Stibbert Library.

In this dialogue of images and gazes, dress becomes a diplomatic language. The exchange of gifts was a key component of Ottoman-European relations. An ambassador might present an illustrated European costume book in Istanbul and receive in return an Ottoman album of similar format. The exchange of images mirrored that of commodities and treaties: representation itself became an instrument of diplomacy. Each power sought to project order, dignity, and magnificence. In this context, clothing functioned as a form of ‘soft power’—a visual negotiation of political and cultural prestige.

The final chapter of Vestire il mondo opens onto a transcontinental horizon, illuminating the visual and textual connections that, over the course of the early modern period, were forged across the Pacific.

Until the late sixteenth century, Japan was virtually unknown to Europeans. No Japanese had ever visited Europe before the diplomatic mission of 1582, when four young envoys, educated by the Jesuits in Nagasaki, were received with wonder in the courts of Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Cesare Vecellio seized the opportunity to update his collection of Habiti, adding in the second edition the image of a young Japanese man—an inclusion that did not merely extend the scope of his work but symbolically marked Japan’s entry into the global visual geography of the known world.

Vecellio arranged his depictions of Asian costumes according to the routes taken by merchants, travellers, and missionaries—itineraries that, beginning in Portugal, circumnavigated Africa to reach India, China, and eventually Japan. With each new edition, he expanded his information about recently discovered or partially Christianised Pacific islands. The addition of the Japanese figure was therefore more than documentary: it was an assertion of the project’s global ambition, the desire to embrace in a single visual repertory the entirety of known humanity.

When the Japanese envoys returned home, they brought with them gifts of immense symbolic and cultural value—among them, Abraham Ortelius’s Atlas of the World, a work destined to have a lasting influence on Japan’s emerging visual and geographical culture. Diplomatic exchanges, the circulation of gifts, and, above all, the activities of Jesuit missionaries played a crucial role in the dissemination of European visual models in Japan and in the subsequent flourishing of Japanese costume books during the Edo period (1615–1868).

As in Europe, this production reflected a new visual culture born of the convergence between scientific curiosity and aesthetic representation. It intersected with Renais-sance geography and with the growing desire to depict the world in a systematic and ordered form. Edo-period Japanese costume books did not arise in isolation but in continuous dialogue with European sources and models—atlases, engravings, maps, travelogues, and ethnographic descriptions. This global vision found expression across an extraordinary range of media: painted folding screens (such as the celebrated Namban byōbu depicting the ‘southern barbarians’, the Portuguese traders and missionaries), maps, illustrated scrolls, popular encyclopaedias, and manuscripts. Each translated into image both the wonder at the world’s diversity and the drive to represent and classify it.

One of the earliest Japanese works of European inspiration is the Bankoku sōzu, or ‘Images of the Peoples of a Myriad Countries’. In this striking composition, the map of the world is accompanied by figures representing the populations of the globe. Along its borders, pairs of men and women embody the hierarchies of value inherited from sixteenth-century European imagery: the quality and abundance of clothing, the colour of skin, and the presence of tattoos or body ornaments serve as indicators of civilisation or barbarism. At the apex of this symbolic hierarchy stands a finely dressed Japanese couple, centrally positioned; at the base, near the margins, a naked pair of Brazilians appear beside a grill on which human limbs are being roasted—a visual allusion to Jesuit narratives depicting Amerindian cannibalism.

This astonishing map, blending geography and ethnographic iconography, shows that Edo-period Japan had not only assimilated Western visual models but also reversed their perspective. It is now the world that is being observed and classified through a Japanese gaze.

A century later, in 1720, there appeared a true book of costumes entitled Mankoku jinbutsushū—The People of Forty-Two Countries—followed by a revised edition in 1801. The differences among these editions are significant, both iconographically and ideologically. The first omits any depiction of Spaniards or Portuguese—by then symbols of the proscribed Christian faith—and explicitly labels Western religion a ‘false doctrine’. The later editions, by contrast, emphasise Japan’s centrality and refinement, portraying the Japanese as an orderly and cultivated people, immune to the supposed menace of European colonisers. Although their visual structure draws on Western prototypes, the world map is completely inverted: Japan stands at the centre, surrounded by the multitude of others.

In its concluding pages, Vestire il mondo restores to us the image of a world that discovers and constructs itself through the act of seeing. Far from being antiquarian curiosities, the early modern costume books reveal the emergence of a new epistemology of the visible—the idea that identity could be read, understood, and hierarchised through the material language of clothing.

And yet, as Calvi so masterfully demonstrates, this process did not generate a single, univocal vision. Rather, it produced a mosaic of interwoven perspectives, in which seeing and being seen become symmetrical and ever-shifting experiences. Each illustration, engraving, and miniature is the outcome of a cultural negotiation—between observer and observed, between local tradition and foreign imagination, between the acts of representing and translating.

The world that emerges from this visual corpus is not a static sum of differences but a living organism animated by exchange, appropriation, and cross-contamination: ‘an emotional and imaginative fabric’, in Calvi’s words, ‘that reveals the world’s interconnections’, the subtle threads that link cultures through images, objects, and bodies.

In this sense, Calvi’s book invites us to reinterpret the visual history of modernity not as the story of a Europe observing the rest of the world, but as that of a global network of gazes—intersecting, mirroring, and endlessly reinventing one another.

[1] Anthony Grafton, New Worlds, Ancient Texts: The Power of Tradition and the Shock of Discovery, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

[2] See Peter Burke, The Historical Anthropology of Early Modern Italy: Essays on Perception and Communication, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987

Giovanni Tarantino Associate Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Florence.

Cromohs (Cyber Review of Modern Historiography), ISSN 1123-7023

DOI: 10.36253/cromohs-16991

RECEIVED: 2 November 2025; PUBLISHED: [TO BE INCLUDED]

© 2025 The Authors. This is an open access article published by Firenze University Press under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.