A Letter on the CROMOHS Debate on Global History

GIOVANNI LEVI

Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

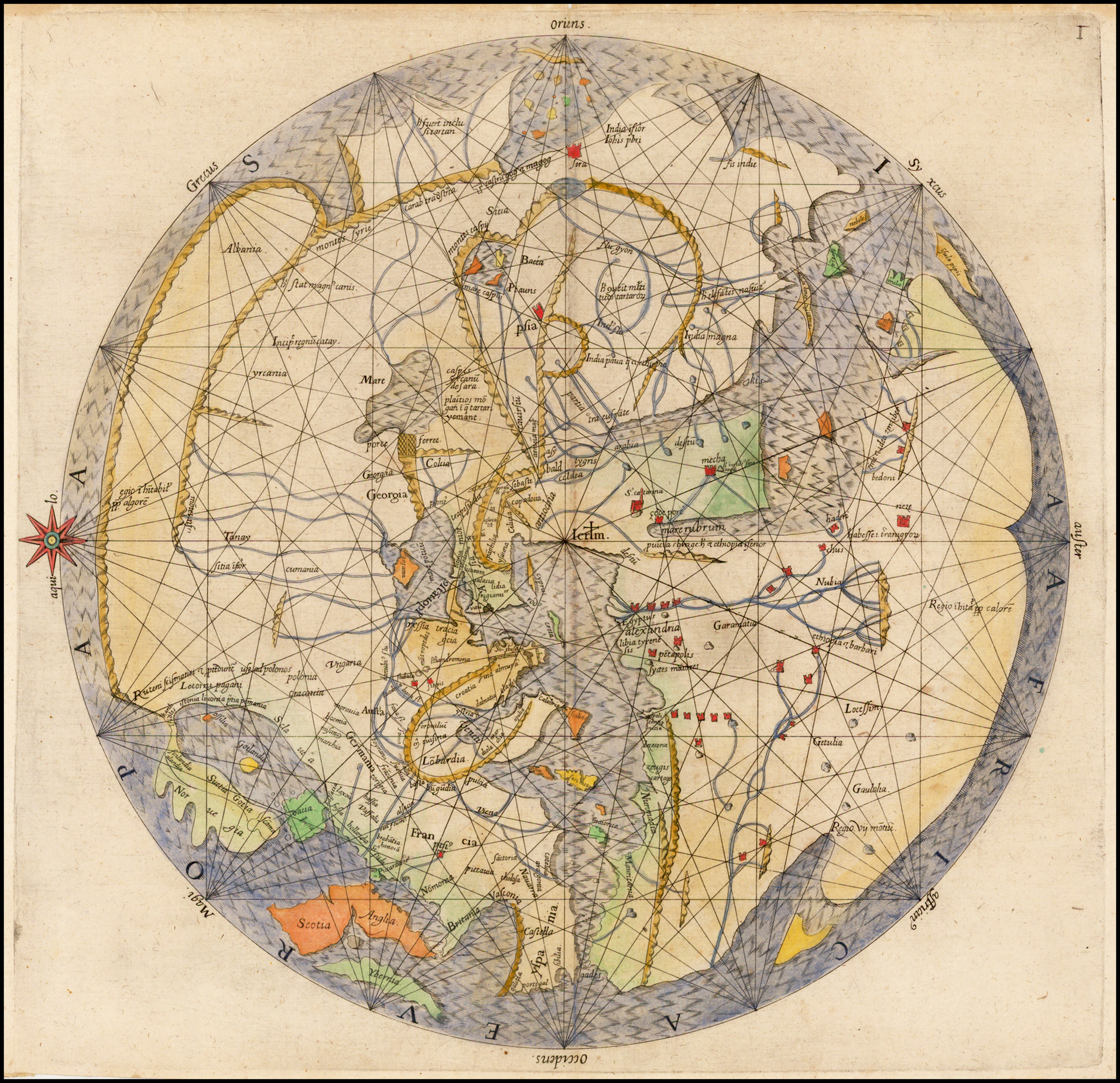

Pietro Vesconte, Mappa mundi, in Marino Sanudo, Liber secretorum fidelium crucis super Terrae Sanctae recuperatione et conservatione, ed. Johann Bongars (Hanoviae : typis Wechelianis, apud heredes Ioannis Aubrii), via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File:World_Map_of_Johann_Bongars_%26_Pietro_Vesconte_(c._1320,_1611).jpg

Dear friends,

I am very late in responding to your invitation to comment on the debate published by CROMOHS on global history. A fortunate delay, it seems, since it appears that the fashion of global history has now entered a crisis, not unrelated to the current international political situation and fragmentation of the ‘global.’ Of course, globalisation and global history are not one and the same thing, but there is undoubtedly some form of family resemblance which is significant for us historians. The context in which we work has inevitable connections with the way we think and the insidious relationship with current events underpins our thoughts.

It seems to me that most of the young historians who make up the European Institute’s Global History Group in Florence show a great deal of resistance to the global history fad, which was still dominant in the autumn of 2020 when the group was founded. The discussion they have contributed to the CROMOHS Current Debates section bears witness to the many doubts that have accompanied the group since its very creation. I find such resistance healthy. With a great deal of common sense, they reject the prevailing practice of simply inserting the word ‘global’ and related ideas of ‘the global’ into the numerous titles of recent research projects or publications, often chaotically, without much thought as to what the word or the related idea imply. Their opinion—which I share—is that, to a large extent, these projects and publications, whether in terms of the sources or the language they deploy, reflect (perhaps unintentionally) an Anglo-Eurocentric perspective, which almost systematically relegates the Other to a subordinate position. As they write, if we wish to foster a ‘truly multipolar and multilingual academic network,’ open the possibility of different types of relations with the past (and thus also with the present) and recover ‘the importance of subjective experience,’ it seems necessary to surpass ‘the present structure of international academia […] that incorporates hierarchies of dominance and sometimes of oppression,’ the effect of which is to erase the plurality of time- and space-dependent processes through which historical knowledge is produced and transmitted. What we thus need is a ‘global’ history that is not insulated from other historiographical practices and does not claim to be a cure-all form of historiography. This reflection on the common entanglement of global histories seems important to me and, after all, has the positive effect of pushing us to be more attentive to the plurality of geo-political, social and cultural worlds we encounter, in the search to provincialise the common Anglo-Eurocentric perspective. However, we must not confuse ‘global’ with ‘connected’: all events and realities must be studied considering all the possible internal and external connections to their contexts, but this is something different from the nebulous image offered by the conspicuous rhetoric of ‘the global.’ Neither the predominance of sources produced by colonial powers, nor the traditional methods and language of scholarship have been challenged, even among those who claim the title of ‘global historians’ (see here Kathryn M. De Luna’s observations on the relationship between written and oral culture, and Pamela Crossley’s remarks on the theoretical weakness of current historiography).

An important debate, it seems to me, is the one between structural functionalism, with its tendency to generalise and leave particularities aside, and the study of particular or individual cases, which allows us to identify new problems and supports the need for new instruments. What general lessons can be drawn from a singular case, event, place or individual life? How do we strike a balance between abusive generalisations and the idea that particular cases, individuals or events can never represent anything greater than themselves? Indeed, some colleagues still seem to think that it is impossible to generalise from a particular case, opposing the local and the global and suggesting that the local never has anything general to teach us. Some of the confusion reigning over the global history movement reflects this problem, which, of course, is also a problem for other disciplines of the humanities and social sciences, or the natural sciences. To make a paradoxical suggestion, the debate between the hidden variables thesis and the quantum correlation of quantum mechanics could perhaps be transposed to history as well. Historiography might be defined as the science of general questions and the search for localised, particular answers. This approach can be extended to other disciplines as well. To give but one example: is it really possible to propose a general theory of economics if we start from the premise that all human beings act according to completely different logics and rationalities? Today, we are trying to counter neoclassical simplicity with new theories, by claiming that the uniformity and therefore predictability of human behaviour is but an illusion.

Another example is provided by psychoanalysis. Here too, general questions produce a range of circumscribed answers. The Oedipus complex poses a general question, but every human being is compelled to deal with his or her own Oedipus complex.

History also has another, more dangerous characteristic. We study the past and therefore, we think we know how things happened, what the consequences of a particular event were. This relationship between an event and its consequences is often summed up in an improper and simplistic vision of causality, as if history were a detective story in which the reader knows the identity of both the victim and the murderer. The weakness of causal explanations is obvious, especially when it comes to drawing generalisations, in that it makes the search for a form of complexity and the reconstitution of particular facts almost entirely useless. Rather, history should be seen as a collective labour: historians write the same book, over and over again; for instance, every year we have dozens of books on Philip II seeking to provide a new reading of known facts in order to come to terms with a reality which is always partial and elusive.

A model presupposing that general questions can produce a range of local and particular answers which, in turn, suggest new general questions, and so on and so forth, was proposed by the Norwegian anthropologist Frederik Barth. I believe precisely this ‘generative model’ allows us to better understand the relationship between individual cases and general questions, while also putting a limit on our generalisations. While relating a case to its effects, it also allows the preservation of what our young Florentine colleagues term ‘the importance of subjective experience.’ From this vantage point, those who speak of the ‘local global’ (or ‘glocal’) have oversimplified the problem, since nothing local can ever claim to be truly global, and no generalisation can ever claim to reveal the richness of a particular case, or of a local and circumscribed micro-history.

This possible encounter between the general and the particular is reminiscent of Kracauer’s opinion, according to which the individual and the collective walk side by side, but never meet. There is, for example, no general definition of beauty that can help us understand ‘the peculiar beauty of a specific work of art.’ Such a ‘general definition exceeds the latter in range, while lagging behind it in fullness of meaning […] The general truth and a pertinent concrete conception may exist side by side, without their relation being reducible to the fact that logically the abstraction implies the concretion […] In fact, the establishment of the general and the settling of the particular are two separate operations.’ It seems to me that while global history may claim to be a clear proposition—or even a method—in truth it has turned out to be a confused and chaotic mess, taking advantage of an academic world in crisis and the weakness of postmodern ideologies in the post-Cold War context dominated by the idea of the inexorable global future promoted by neoliberal ideologies. A fundamental illusion consists in the idea that the historian’s work gains in ‘globality’ as soon as he or she addresses a diluted space, without seeking to understand the profound diversity of connected spaces and contexts which may respond to completely independent logics and require completely different reading and interpretation methods. Certainly, positive propositions can emerge from connecting things together, but this does not automatically produce a ‘global’ reality. I will cite three positive examples, which unfortunately are only rarely referred to in works bearing the label ‘global history’:

- The intensive study of connections in consideration of the plurality of local causes illuminating the object of inquiry (see here S. Subrahmanyam’s critique of S. Conrad, R. Bertrand and A. Mikhail)

- Total history, as already theorised in the 1960s by some French historians, in particular Nathan Wachtel who, in his extraordinary essay of regressive history on the Urus of Bolivia but also in his large-scale research on New Christians in the Spanish Empire, considered the Atlantic space as a whole while at the same time focusing with almost maniacal precision on aspects of micro-history in the constrained space of the Urus reductions.

- The generative model formulated by Barth and mentioned above, which seeks to explain the unpredictability of normative systems, too often understood in terms of their apparent stability over very long periods of time.

Two contributions to the debate published by CROMOHS also offer a critique of the simplistic nature of global history in its most common forms. Kathryn M. De Luna thus interrogates the use of the word ‘global’ when describing large-scale interactions without considering the problems raised by our sources, in particular when the latter tend to neglect or hide from view the more negative effects of ‘globalisation’ on the distribution of wealth, or when scholars make almost exclusive use of Eurocentric material to the detriment of other sources, including oral sources for instance (after all language is our only global resource). Indeed, she sees these as a universal archive and repository through which we may balance our Eurocentric perspective, ask new questions and seek new ways to conceptualise ‘global’ processes. In order to do this, new methods are necessary.

Pamela Crossley also clarifies her opinion that global history is a chaotic and disappointing historiographical trend. It appears incapable of defining its specificity or explaining the model it seeks to construct, and more generally, how it needs to be distinguished from historical sociology. How exactly does global history claim to renew our research methods, in particular the critical reading of documentary historical sources? And how does it relate to the current phenomenon we call ‘globalisation’? Is it a kind of passive relationship, or some sort of fashion trend?

The interview with Sanjay Subrahmanyam, also published by CROMOHS, and his essay co-written with Cornell Fleischer and Cemal Kafadar, ‘How to Write Fake Global History,’ both seem very important to me. Subrahmanyam is undeniably an extraordinary historian. He also looks at global history with a hint of condescension, seeking not so much to establish a distinct field of research but rather to define the limits of ‘global’ historical research and prevent any confusion. His polemic with Conrad, Bertrand and Mikhail is both ironic and ferocious, and illustrates how in the end the disorderly wave of adherence to a historiographical project with such vague outlines as global history proved moot. He nonetheless credits the practitioners of global history for having contributed to breaking the constraints imposed by area studies and for having used comparison to emphasise the contrast and differences of our fragmented and diverse world. But the aim of such research should be to enlarge the geographical and chronological scale of our work, not to reduce everything to static morphologies. Subrahmanyam’s project, as he himself describes it, encourages ‘connected’ rather than ‘global’ histories, rooted in a constant dialogue with archives and primary sources. On the question of the relationship between the general and the particular, Subrahmanyam writes: ‘The particular only makes sense in relation to the general.’ Immediately afterwards, however, he clarifies this assertion, insisting on the fact that ‘one uses the particular to build towards the general, but also to question it. When a general history becomes so distant and disconnected from the particular that it is absolutely impervious to contradiction or modification, it has, in my opinion, become pretty useless’ (here he is referring in particular to the theses of I. Wallerstein). Synthesis is thus necessary, but it must first and foremost be considered a teaching tool.

Behind all these assertions lies an ill-defined problem, to which Subrahmanyam’s work bears witness: while engaging in ‘connected histories,’ he is also a remarkable micro-historian. His work allows us to confirm F. Barth’s view, quoted above, that historiography is a science of general questions but localised answers. We could thus turn Subrahmanyam’s claim on its head and say that ‘the general only makes sense in relation to the particular.’ Or, to paraphrase Kracauer, suggest that the particular and the general walk side by side, but never meet. The particular nestles in our sources, and it is these same sources that raise general questions. The general, by contrast, is never more than a hypothesis, a question. Only the study of localised sources enables us to make progress in our work and our wish to approach and understand as much as we can an inexhaustible ‘reality.’

To conclude: the debate proposed here by the members of the European Institute’s Global History Group also addresses the political dimension of so-called global history. This, I believe, is a fundamental issue. As underlined by Subrahmanyam and J. Adelman, it would certainly be a mistake to link global history and globalisation too closely. What global history offers bears no relation to its object of study, namely connections and their effects, large-scale phenomena and the (positive or negative) social consequences of global nexuses. It should also be noted, however, that the debate over global history emerged when the bipolar world of the postwar period came to an end, and neoliberal ideologies became the new global norm. In this context, an impressive flood of money enabled the creation of academic chairs and institutes, specialised journals and research projects, all supported by the idea of an ineluctable march towards progress, globalisation and global capitalism. We need to reflect on the ideological effects this sudden obsession for global history may have beyond the world of scholarship, in particular when it simply seeks to create an image of history which is both complacent and dangerous. Slowly, we have also witnessed the emergence of a plurality of sub-forms of imperialism, a new fragmentation of the world. The things that did become more ‘global’—finance, the economy, information and migratory movements—do not summarise the changes we have seen over the last few decades. These changes have not been accompanied by another, even slower form of globalisation, namely the globalisation of political and social control over these same realties.

Thus, the question remains: has the globalist fad truly led to more connected forms of historiography, or has it merely used the label of global history to reproduce (consciously or unconsciously) a certain form of Anglo-Eurocentric, neoliberal historiography which is nothing more than a teleology of progress—another, perhaps dominant, example of ‘fake global history’? In my view, the young colleagues from the European Institute have sensed this political pitfall with great clarity: the historian’s work is nothing if it is not accompanied by a healthy practice of doubt and reflexivity.

The world has always been multicentric and interconnected, and historians need to intensify their focus on this interconnectedness. But ‘global’? The word reflects a troubled image, and perhaps a politically charged and dangerous ideology.

[1] Siegfried Kracauer, History. The Last Things Before the Last, 2nd ed. (1969; Princeton: Markus Wiener, 1995), 206.

[2] Nathan Wachtel, Le retour des ancêtres. Les indiens Urus de Bolivie. Essai d’histoire régressive (Paris: Gallimard, 1990).

[3] See his polemic with Clifford Geertz in Frederik Barth, Balinese Worlds (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993). On the generative model, see Barth, Selected Essays of Frederik Barth. vol. 1, Process and Form in Social Life (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981).

Giovanni Levi Professor Emeritus at the University of Venice, Giovanni Levi is one of the pioneers of microhistory.

Cromohs (Cyber Review of Modern Historiography), ISSN 1123-7023

DOI: 10.36253/cromohs-14611

RECEIVED: 3 July 2023; PUBLISHED:18 July 2023

© 2023 The Authors. This is an open access article published by Firenze University Press under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.