The Global Relevance of the Legal History of the Early Modern Mediterranean*

MARIA FUSARO

University of Exeter

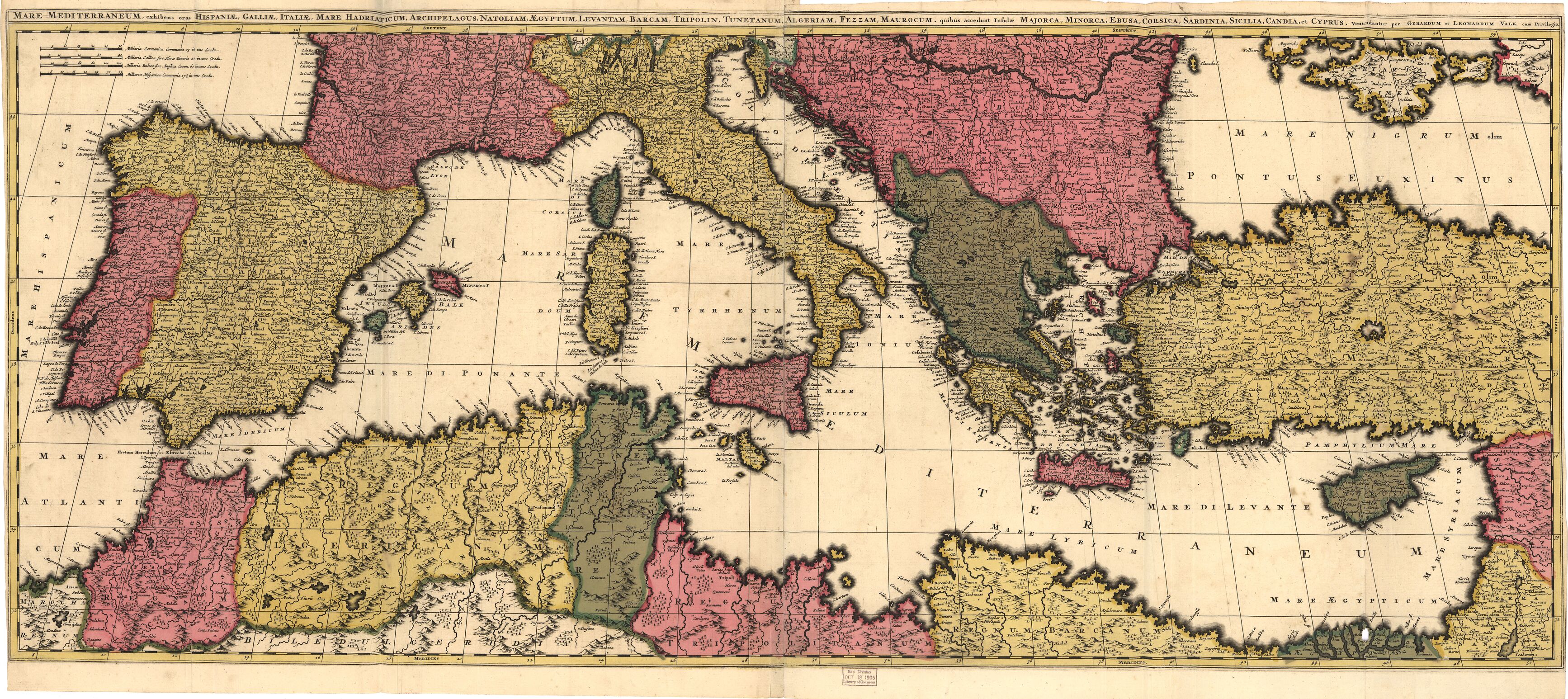

Gerard and Leonard Valck, Mare mediterraneum, Washington, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, G5672 .M4 1695 .V3 TIL, 1695. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division (Public Domain) https://www.loc.gov/resource/g5672m.ct000433/.

Not much is solved

with the gun and the whip.

The very idea that all is a pun,

a play of syllables is the most credible.

Not by chance in the beginning was the Word. [1]

EUGENIO MONTALE

At the centre of global history historiography there is a yawning gap where the early modern Mediterranean should be and I shall argue that we need to turn our gaze back to the ‘European lake,’ looking at its legal history and the ways it was shaped by commercial activities in those centuries.

I shall start by sketching the importance of framing the differences between global and world history, as the necessary background to the importance of the interactions of different legal systems in the Mediterranean, and their effect on the framework of European global expansion. Focusing on the intersection between legal, maritime and global histories, I will develop this argument within the framework of recent historiographical developments across different sub-disciplines and national historiographies, and argue that the early modern Mediterranean was the laboratory for a dialogue between different legal systems which has an extreme relevance over the longue durée.

Global and World History

Words are the main tools of the historians’ craft and, as is frequently the case, problems start with their definition (or lack thereof). Two key concepts for this essay are those of global history and world history.

Global history is flourishing also because of its connection with globalisation, a contemporary phenomenon which impinges on everyone’s lives, and the study of which has been informed—since its beginning at some point in the nineteenth century—by very strong ideological connotations. To make the matter more complex, we should not forget that a ‘fundamental confusion attached to the globalisation concept derives from its simultaneous definition as a process and an outcome.’ [2] World history is another strong subfield, and I would argue that even though the two expressions are frequently used as synonyms, they are not. World history is also concerned with globalisation, however, it has been developed mainly along the lines of a critique of Eurocentrism (and its twin, Orientalism) and is therefore firmly connected with social and cultural history. It has, therefore, concentrated more on common patterns of historical development. This to me makes global history more akin to economics and economic history, whilst world history is in a closer dialogue with anthropology and sociology.

Global history has traditionally had a less critical approach towards the history of the ‘West’ something that comes from its closer engagement with economic history. The strength of economic history (and a fortiori economics) in shaping the analytical categories behind global history can be seen in the sharp and incisive nature of the distinction between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ globalisation, with the latter a measurable entity defined by market integration. Indeed, for a long time these two disciplines have set the dominant methodological approaches, but this is only one side of the story. Looking at the matter from another angle, if one views globalisation as ‘the process which increases the interconnectivity of social, economic and cultural activities across the globe,’ then the main concern of global history is interconnectivity, and the creation of ever-more complex transnational systems that manage contacts across different areas of the globe. World and global histories are, therefore, analytically different but intimately linked, because the patterns studied in world history are those which are affected by the phenomena studied in global history, and because world history is largely a reaction and is intended to constitute a corrective, to global history. [3]

The Place and Importance of Legal History

We call the set of rules and the social structures which make the law and make it work a ‘legal system.’ [4] The history of these processes is part of the history of patterns of development and is therefore part of world history. It is also an integral part of the study of the original part of the discipline of comparative law, the comparison of two or more legal orders. Ideally, such a comparative study would, like global history, also involve disciplines such as anthropology and sociology. In a study of any depth, history is an essential element, as is jurisprudence. [5]

When groups come into contact, rules develop to facilitate their dealings and, if there is sufficient interaction, the legal system of one group may well influence the legal system of the other group. If there is an imbalance of power, the law created by these actions will favour the interests of the more powerful group. The history of these processes is part of the history of the connection of patterns of development, and the effects of that connection on those patterns, and is therefore part of global history. It is also an integral part of the study of some more recent parts of the discipline of comparative law, especially those related to legal transplants, harmonisation and legal pluralism. Here too, ideally such a comparative study would also involve other disciplines. In this regard, therefore, comparative law and legal history are very similar. [6] In both, to borrow some terms from linguistics, one needs to take account of the synchronic and the diachronic. That said, it is the main characteristic of global history, connectivity, which drove—and still drives—the development and geographical spread of law, and made the expansion of European law across the world a very significant form of globalisation.

This is one of the aspects of law which makes it such an important part of all the histories mentioned above. The spread of European law was the earliest form of globalisation. It was already an integral part of the first, late-fifteenth-century explorations, thus substantially predating any form of economic globalising forces. [7] On this ground alone, therefore, it cannot be neglected in global and world histories. However, law also played a vital role in another key aspect of European imperialism, the fight for global supremacy. This struggle—be it economic or political—was fought not just by force of arms, money, or both, but also with the law. This was especially the case when the struggle took place far from Europe.

What I would like to discuss now is precisely where the partition I proposed between global and world history leaves ‘legal history.’ Fully aware that it can be positioned in both camps, I shall argue that it falls a bit more on the side of ‘global’ history, as the history of the law is intimately connected with ‘increased connectivity’ as this is what drove—and still drives—its development and geographical spread. In other words, my argument is that legal history can truly link economic, social, political and cultural analyses on the global scale. [8]

And here is where the history of legal interactions within the early modern Mediterranean becomes central to global history. I would also argue that legal history needs to be brought into ‘new Mediterranean Studies.’ One quite typical list of topics falling under the rubric of Mediterranean Studies is: ‘political, social and aesthetic consequences of globalization; empire; migrations into, within, and from the region itself; trade and the movement of capital; piracy, captivity and slavery; cultural diffusion; religious conflict and assimilation; the environment; scarcity technology; diplomacy; gender; cultural hybridity; and modernization.’ [9] No mention of ‘law’ or ‘legal history.’ [10]

This absence is glaring considering the current active role played by legal history within Mediterranean historiography, which is particularly evident in studies focussing on its Muslim polities, until very recently ignored by mainstream historiography. Very stimulating contributions are dedicated to the history of Ottoman law, to the legal frameworks of diaspora communities, to the legal basis of corsairing and piracy in the Mediterranean, and the role of commerce and commercial law in the political and legal transformation of the region at large. [11] The types of activities in which legal interactions took place were many and various, as were the types of people involved and the effects on the societies encountered. Or, taking a legal point of view, a wide variety of ‘laws’ were involved.

Connectivity, Interactions and the Importance of the Mediterranean

Connectivity is the factor which gives the Mediterranean its relevance for global history. The Mediterranean is a lot more than a ‘small sea with a big historiography.’ [12] Indeed, it is precisely its small, contained space and the consequence of those characteristics which make it ideal for an examination of the interplay of powers and the ways in which they shaped the modern world. Properly introducing the Mediterranean within the current ‘global history’ debates is not to reinstate a form of Eurocentrism, if anything exactly the opposite, as the social structures and economic performances of some countries bordering its shores were among the first victims of globalisation. The investigation of solutions originally devised to counteract the effect of proto-globalisation can also have some relevance for issues of contemporary policy, as Europe today is facing challenges of a similar nature. The Mediterranean was—and, rather painfully, still is—‘the most vigorous place of interaction between different societies on the face of the planet,’ as David Abulafia stated on the last page of his The Great Sea. [13] It is an ideal area for examining how the clashes and overlapping of powers and jurisdictions within the maritime world ended up shaping international relations during the early modern period.

When the Mediterranean is analysed within a global history framework, it is usually for the period from the nineteenth century onwards. [14] This is, of course, a very important time which was, inter alia, a turning point for the history of the Middle East and North Africa. However, the earlier period from the last quarter of the sixteenth to the end of the seventeenth century—before the nation-state, and before the implementation of properly ‘national’ commercial strategies—saw in the Mediterranean a far greater intermingling of nationalities and interests than would be the case in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. [15] It was a situation which has interesting resonances with the present condition of international maritime trade, which is experiencing profound structural, legislative and governance changes brought about by technological development (then the introduction of new construction techniques, today containerisation, a huge increase in the size of ships, modern communications, and so on) and by the entrance of new shipping nations (then the English and Dutch, today the Chinese). [16]

A further example is that of the contest for worldwide maritime sovereignty. In the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the local powers Europeans encountered did not have recognisable sovereignty claims over extensive or deep waters. In the Indian Ocean the Europeans’ superior naval power played an important role in the shaping of negotiations and exchanges with local authorities, so Europeans could usually effectively overrule, or just ignore, local claims. [17] The result of this situation was that the worldwide sovereignty contest was played, mostly, internally, that is to say amongst European states on the ‘neutral’ fields of the world’s oceans.

The fight for European supremacy within Europe, especially on Mediterranean waters, presents a different set of issues and questions as the Mediterranean was an area thick with established and competing jurisdictions, none of which could be easily crushed or ignored as it happened in other seas. This fight played out not just on the military and diplomatic fronts, but also in the courts of justice.

Lauren Benton’s work has been path-breaking on the jurisdictional fights related to European global expansion. [18] However, her analysis focuses mostly on political and military confrontations, whilst I would argue that it is equally important to take into account also those ‘peaceful’ daily interactions concerned with the practical functioning of trade and related litigation. It was in the early modern period that many significant Capitulations were granted by the Ottoman Empire to some European states, enabling Western-style law to enter the Islamic world for the first time and unwittingly preparing the ground for the eventual replacement of the Sharīʿa legal systems of the region with Western-style ones, together with the marginalisation of the Sharīʿa itself and the abolition of many of its parts. [19] This process ended up shaping the entire legal systems of many modern countries in the Middle East and North Africa, and profoundly influenced many others. [20]

On Modernity and Decline

The neglect of the Mediterranean within the fast-expanding historiography on global history has many roots. [21] As already indicated, this is a serious methodological and intellectual shortcoming, as the Mediterranean never lost its centrality in the political and military strategies of all European nations, particularly those with imperial ambitions, through early modern and modern times. Even those countries with a primarily or exclusively Atlantic seafront felt the need to establish their presence in the Middle Sea. However, in contemporary scholarship the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean are always presented—whether directly or indirectly—as the primary loci of early modern globalisation and modernisation. [22]

In this regard allow me to be frank and provocative: one cannot help but have the impression that globalisation is sometimes considered as something that happened only in far-away places—and this ‘far-away’ is relative to Europe of course, which brings us back to the Eurocentrism mentioned earlier in a very embedded and structural way—rather than something established through connections with far-away places and, by its own intrinsic nature, a phenomenon whose effects are felt on the global scale, that is to say, everywhere. In other words, globalisation appears to be usually discussed either in terms of what happened away from Europe, or in terms of what Europe did to other places, while its impact within early modern Europe and the Mediterranean has been less discussed. This is a variety of Orientalism in itself.

I have argued at length elsewhere that ‘the crisis of Venice and the rise of England can be seen as two early examples of the opposite consequences that the beginning of European expansion and the onset of proto-globalisation had on the old continent.’ [23] The issue of how to confront the narrative and analysis of the concepts of ‘crisis and decline’ is central to the relationship between Mediterranean and global history, as the tale of Mediterranean decline is repeated as a mantra to justify its neglect. Fernand Braudel—the father of Mediterranean history—started this himself when he argued for Mediterranean decline from the 1580s or, in a later revised analysis, at the latest from the middle of the seventeenth century, [24] and David Abulafia, in his recent synthesis on the human history of the Mediterranean, even predates its onset to 1494. [25] It is not my intention to challenge the existence of economic decline in the early modern Mediterranean, although I would argue—borrowing the effective expression of David Landes—that it is more correct to define it as a ‘loss of (economic) leadership.’ [26] What is puzzling is the resilience of an underlying (probably even unconscious) Whiggish tone within early modern economic history, which seems to assume that the phenomenon of ‘decline’ is less analytically relevant, less deserving of attention and explanation, than that of ‘rise,’ both from the purely intellectual and the more practical policy perspective. [27]

From the legal perspective, the long-term relevance of Mediterranean development for global history becomes exceedingly relevant. The small and crowded space of the Mediterranean was not unique in its interconnectivity. [28] However, it is within this basin that poly-sided comparative legal developments come into particularly sharp focus, as also do the ways in which these issues, as they played out on the international stage, affected economic exchanges and diplomatic relations between states.

Jurisdictions and Law

Throughout the world the administration of justice has always been one of the fundamental prerogatives of power; even taking into account the great variety and resilience of local customs and usages which resisted governments’ centralisation efforts for centuries at home, European states’ expansion was expressed first and foremost by the expansion of their legal systems, which quickly became dominant, achieving that position of hegemony which they still hold today. [29]

From the late medieval universal and global religious and jurisdictional ambitions which formed the legal basis of the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), and the ways this was misinterpreted across the centuries, [30] to the legal ‘ceremonies of possession’ which characterised European practices of claiming sovereignty over territories around the globe, European law systems were the first to globalise, substantially predating any economic activity. [31] Unlike what happened in the rest of the globe, where pre-existing local claims and jurisdictions could—and frequently were—ignored, this kind of behaviour could not—and did not—happen in the Mediterranean.

The extreme interconnectivity of the Mediterranean, constantly reiterated in the secondary literature, is usually described thus: a ‘diversity of languages, religions, cultures, and political systems within close, easily navigable proximity.’ [32] But to me, this just sets the stage, as there are two further elements which are even more important from a global perspective: this abundance of active and competing jurisdictions—frequently contested, sometimes shared, and in actual practice overlapping and jostling for primacy—was the emanation of powers and states which mutually recognised each other. Connatural with this was the fact that, in the vast majority of interactions between expanding Europeans and local authorities across the globe, there was not effective mutual recognition, nor in many cases proper ‘understanding’ between the different systems of justice/administering law, and this was particularly the case when the conflict was based on the seas. Mutual recognition of land-based jurisdictions was a less problematic situation, and there were plenty of such examples across the globe. [33]

All players in this game acknowledged each other’s legal authority and sovereignty and thus their interactions and conflict were based on attempts at expanding the extension and reach of jurisdictions, not on their existence and validity. This common legal culture and language is what allowed such intermingling between different legal systems.

On Legal Systems and Hybridity

Plurality (and overlapping) of powers with a judicial remit, and therefore of jurisdictions, was a defining characteristic of the early modern period. The analysis of how economic interactions in the pre-modern Mediterranean fostered and shaped historical development in the region and beyond is a topic currently undergoing a profoundly revisionist phase. The common approach of these new works is to overcome the classic model of the institutional and territorial integration of the region as a consequence of the mere diffusion of European institutional models and legal codifications. Assuming this approach, the study of commercial litigation has recently become the main object of study for the analysis of encounters between European, North African, and Middle Eastern merchants and seamen, each with different legal cultures and judicial practices. [34]

The goal of the ConfigMed project was to produce detailed analyses of legal developments across the region, whilst avoiding the traditional paradigm of a linear Europeanisation. [35] These comparative analyses of commercial litigation and extra-judicial solutions, also including disputes involving litigants who were not subjects of the local authorities or, as was frequently the case, whose legal status was linked to their religious identity. In Wolfgang Kaiser’s words, ‘the encounters of Muslim, Jewish, Armenian, Protestant merchants and sailors, with different legal customs and judicial practices, appear as the social site of legal and cultural creativity.’ The overarching scope of ConfigMed was therefore to achieve a ‘more precise and deeper understanding of the practices of intercultural trade, in a context profoundly shaped by legal pluralism and multiple and overlapping spaces of jurisdiction.’ [36] These are definitely global patterns, but in parts of the early modern Mediterranean these were indeed unusually dense forming the basis of daily intercultural exchanges and legal cross-fertilisation. [37]

The intellectual framework of projects such as ConfigMed, and Making of Commercial Law [38] well highlights a further element of crucial relevance for the study of Mediterranean history under a global interpretative lens, something directly connected with contemporary political reality and legal jostling. The three legal ‘systems’ and traditions which ended up dominating the globe with utter and unquestionable hegemony—Civil, Common and, to some extent, Islamic law [39]—had in the Mediterranean their most active interactions since the ‘invasion of the Northerners’ of Braudelian fame in the last quarter of the sixteenth century. [40]

The CIA publishes a World Factbook, with a wealth of data not just on states, but of ‘administrative divisions (in the [US] Government category)’ providing details about the legal systems which these use. [41] This is not the place to discuss the methodology behind the data collection, the rationale behind these partitions nor, indeed, the political agenda behind this most interesting exercise, but this is just a simple way to provide some very rough statistics about the dominant legal systems today in 2023. [42]

Out of a total of 260 ‘administrative divisions’ listed, it would not come as a surprise to learn that very few have what can be defined as a ‘pure’ legal system, and the vast majority administer justice through a mix of different systems: 54 percent rely primarily on civil law—of various traditions, but all traceable back to Roman ius commune (with the French, Dutch and Spanish varieties as the most common); 32 percent rely primarily on Common Law—with either a British or American flavour; 12 percent rely on a fairly even mixture of these two (with a variable predominance between the two elements). Of the total, 11 percent include elements of Islamic law, but only Iran is described as exclusively reliant on it. [43]

‘Europe’ and the ‘West’: A Conclusion

This tripartite—Civil, Common, Islamic—long-term mutual engagement between legal systems is what makes the early modern Mediterranean a crucial laboratory of global history. The central point is not so much about the expansion of European law across the globe per se, more the fact that the European epistemological approach to the administration of justice, and the creation of law as the embodiment of authority, was imposed wherever Europeans arrived and settled, regardless of their mode of conquest and of the justifications employed to support their claims. Indeed, this European intellectual structure took root well beyond European imperial expansion, and spread its tendrils into countries which were never subject to European rule.

Only in the last few decades have alternative legal systems—such as Islamic law (mostly, but not exclusively, Sharīʿa)—started to expand again and to challenge the hegemony of European systems. [44] The practical modalities of this phenomenon of cultural expansion are just starting to be investigated. [45] However, for all intents and purposes, these solutions are not really alternatives to the Western model of law, but more attempts to accommodate some principles of Islamic law within a Western framework. Here the issue of the scale of analysis takes centre-stage, and the centuries-long interplay between the three hegemonic legal systems in the Mediterranean can be a most fruitful focus of analysis exactly because of the relatively small scale of the region. [46]

The magnitude of the success of civil and common law in colonising the globe has fostered a general impression, also amongst scholars of Europe, that ‘Europe’ and the ‘West’ perfectly overlap, that the West was ‘one,’ and that there was no possible alternative to what happened as the shape and form of the present global economy is built on the foundation of early modern ‘European’ commercial imperialism. This, buttressed by the triumphs of the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent global expansion of the British Empire in the nineteenth century, has contributed to a flattening of the European ‘experience’ within the folds of the Anglo-American dominated nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Historiography followed suit. But there were alternatives, and the resurgence of Islamic legal traditions across the globe today is in itself evidence of the long-term survival of alternative way of conceiving the legal epistemic framework and socio-political structure of societies.

Law is a fundamental tool of identity. The current debate on the different nature of English laws and legal system compared to those of continental Europe, is daily unfolding and proving to be the most thorny, politically and culturally sensitive element of the present post-Brexit negotiation between the UK government and the EU, and blazing evidence of the resilience and relevance of these issues over the longue durée. [47]

[*] This essay has benefited from the comments of audiences at the Huntington Library, and at the Universities of Yale, Exeter and Oxford. I benefitted from conversations with Lauren Benton, Nick Foster, and Francesca Trivellato, and their comments and suggestions greatly improved my thinking. The usual disclaimers apply. My reflections developed during my work in three research projects: LUPE-Sailing into Modernity: Comparative Perspectives on the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century European Economic Transition (Starting Grant 284340 – P.I. Maria Fusaro), AveTransRisk – Average – Transaction Costs and Risk Management during the First Globalization (Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries) (Consolidator Grant 724544 – P.I. Maria Fusaro), and ConfigMed – La reconfiguration de l’espace méditerranéen: échanges interculturels et pragmatique du droit en Méditerranée, XVe-début XIXe siècle (Advanced Grant 295868 – P.I. Wolfgang Kaiser). This essay is dedicated to the memory of Cornell Fleischer, a true friend.

[1] Eugenio Montale, Quaderno di quattro anni (Milan: Mondadori, 1977), 116: ‘Si risolve ben poco/con la mitraglia e col nerbo. / L’ipotesi che tutto sia un bisticcio, / uno scambio di sillabe è la più attendibile. / Non per nulla in principio era il Verbo’ (translation by Jody Fitzhardinge and Lorenzo Matteoli).

[2] Jan de Vries, ‘The Limits of Globalization in the Early Modern World,’ Economic History Review 63, no. 3 (2010), 710–33 (711).

[3] I fully develop these considerations in Maria Fusaro, ‘Maritime History as Global History? The Methodological Challenges and a Future Research Agenda,’ in Maritime History as Global History, eds Maria Fusaro and Amélia Polónia (St John’s, Newfoundland: International Maritime Economic History Association, 2010), 267–82, and bibliography therein quoted.

[4] The word ‘law’ has several meanings, each of which involves linguistic complexities. The term ‘legal system’ has fewer difficulties associated with it, but it is ambiguous, having both the meaning given above and ‘body of rules’ (i.e., law in the meaning given above) viewed as a system in itself. I wish to thank Nick Foster for our conversations on these issues.

[5] On the benefits and difficulties of achieving this in practice see Nicholas H.D. Foster, Maria Federica Moscati, and Michael Palmer, eds, Interdisciplinary Study and Comparative Law (London: Wildy, Simmonds and Hill, 2016); and Vernon V. Palmer, ‘From Lerotholi to Lando: Some Examples of Comparative Law Methodology,’ American Journal of Comparative Law 53, no. 1 (2005): 261–90. In the common law tradition, the term ‘jurisprudence’ means ‘legal theory.’ The meaning ‘case-law’ is much less common, and is only used in an international context, never when referring to common law case-law.

[6] Heikki Pihlajamäki, ‘Merging Comparative Law and Legal History: Towards an Integrated Discipline,’ American Journal of Comparative Law 66, no. 4 (2018): 733–50, and the other contribution to this issue dedicated to ‘Legal History and Comparative Law: A Dialogue in Times of the Transnationalization of Law and Legal Scholarship.’ See also: Thomas Duve, ‘Legal traditions: A dialogue between comparative law and comparative legal history,’ Comparative Legal History 6, no. 1 (2018): 15–33.

[7] Shaunnagh Dorsett and John McLaren, eds, Legal Histories of the British Empire: Laws, Engagements and Legacies (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014); Lauren Benton, A Search for Sovereignty. Law and Geography in European Empires 1400-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Patricia Seed, Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[8] On the challenge of discussing ‘legal history in a global perspective,’ see Thomas Duve, ‘Global Legal History: Setting Europe in Perspective,’ and James Q. Whitman, ‘The World Historical Significance of European Legal History: Historiography and Methods,’ in The Oxford Handbook of European Legal History, eds Heikki Pihlajamäki, Markus D. Dubber, and Mark Godfrey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 115–139, 3–21; this is also essential reading on the thorny debate on how the supposed European legal superiority forged modernity and led to Europe’s global hegemony, an issue I shall not discuss within this essay.

[9] John Watkins, ‘The New Mediterranean Studies: An Institutional and Intellectual Challenge,’ Mediterranean Studies 22, no. 1 (2014): 88–92. The legal element is equally absent from a most recent ‘manifesto’ volume on the field: Brian A. Catlos and Sharon Kinoshita, eds, Can We Talk Mediterranean? Conversations on an Emerging Field in Medieval and Early Modern Studies (London: Palgrave, 2017); and from Filippo De Vivo, ‘Crossroads Regions: The Mediterranean,’ in The Cambridge World History, eds Jerry H. Bentley, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, vol. 6, part 1: The Construction of a Global World, 1400–1800 CE. Foundations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 415–44. A more nuanced view in Veli N. Yahsin, ‘Beginning with the Mediterranean: An Introduction,’ Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 34, no. 2 (2014): 364–67.

[10] On the issues surrounding ‘area’ studies today: Alessandro Stanziani, ‘Global History, Area Studies, and the Idea of Europe,’ Cromohs 24 (2021), doi: 10.36253/cromohs-12562.

[11] Amongst a fast-growing field, see: Wolfgang Kaiser and Johann Petitjean, eds, ‘Litigation and the Elements of Proof in the Mediterranean (16th-19th C.),’ Quaderni Storici 51, no. 3, monographic issue (2016); Jessica M. Marglin, Across Legal Lines: Jews and Muslims in Modern Morocco (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016); Georg Christ, Franz-Julius Morche, Roberto Zaugg, Wolfgang Kaiser, Stefan Burkhardt, and Alexander D. Beihammer, eds, Union in Separation: Diasporic Groups and Identities in the Eastern Mediterranean (1100-1800) (Rome: Viella, 2015); Joshua M. White, Piracy and Law in the Ottoman Mediterranean (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017); Francisco Apellániz, Breaching the Bronze Wall: Franks at Mamluk and Ottoman Courts and Markets (Leiden: Brill, 2020); Tijl Vanneste, Intra-European Litigation in Eighteenth-Century Izmir: The Role of the Merchants’ Style (Leiden: Brill, 2022). The contemporary implications of these issues are discussed in: Heba Sewilam, ‘Does Sharīʿa Need to Be Restored? The Legislative Predicament of the Sunnī Doctrinal Theories,’ Arab Law Quarterly 33, no. 1 (2019): 58–80; and in the work of Changing Structures of Islamic Authority and Consequences for Social Change: A Transnational Review, an ERC-funded project led by Masooda Bano, more details at https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/337108.

[12] Jokingly described as such by an eminent global historian in a private conversation.

[13] David Abulafia, The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 648.

[14] See: Paul Caruana Galizia, Mediterranean Labor Markets in the First Age of Globalization. An Economic History of Real Wages and Market Integration (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015); Şevket Pamuk and Jeffrey G. Williamson, eds, The Mediterranean Response to Globalization before 1950 (London: Routledge, 2000).

[15] Molly Greene, ‘Beyond the Northern Invasion: The Mediterranean in the Seventeenth Century,’ Past & Present 174 (2002): 42–71.

[16] For a synthetic analysis of the impact of China in contemporary maritime trade in the Financial Times see James Kynge, Chris Campbell, Amy Kazmin, and Farhan Bokhari, ‘How China rules the waves. FT investigation: Beijing has spent billions expanding its ports network to secure sea lanes and establish itself as a maritime power,’ Financial Times, January 12, 2017, https://ig.ft.com/sites/china-ports/?mhq5j=e7.

[17] On the lack of evidence of local doctrinal tradition in Asia for claiming the seas, see: Stephen C. Neff, Justice Among Nations: A History of International Law (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 131–35; see also Philip E. Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[18] Lauren Benton, ‘Legal Spaces of Empire: Piracy and the Origins of Ocean Regionalism,’ Comparative Studies in Society and History 47, no. 4 (2005): 700–24.

[19] On this see the classic: Maurits van den Boogert, The Capitulations and the Ottoman Legal System: Qadis, Consuls, and Beratlıs in the Eighteenth Century (Leiden: Brill, 2005); a recent reassessment of the state of the art, with up to date bibliography in ‘Contacts, Encounters, Practices: Ottoman-European Diplomacy, 1500-1800,’ Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal Of Ottoman Studies 48 (2016), monographic issue, especially Michael Talbot and Phil McCluskey, ‘Introduction,’ 269–76. For a technical legal perspective Nicholas H.D. Foster, ‘Commerce, Inter-Polity Legal Conflict and the Transformation of Civil and Commercial Law in the Ottoman Empire,’ Yearbook of Islamic and Middle Eastern Law Online 17, no. 1 (2011–2012): 1–49, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/2211-2987_001.

[20] Foster, ‘Commerce, Inter-Polity Legal Conflict.’

[21] Notwithstanding a pioneering and classic analysis of its position within the medieval world system, and a few volumes dedicated to the impact of contemporary globalisation processes upon the economy of the region: Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991); Caruana Galizia, Mediterranean Labor Markets; Pamuk and Williamson, eds, The Mediterranean Response.

[22] A connection elegantly summarised in David Armitage, ‘Three Concepts of Atlantic History,’ in The British Atlantic World: 1500–1800, eds David Armitage and Michael J. Braddick (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 11–27. Some titles openly connect the Atlantic and modernity: from the classic Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1993), to the recent A.B. Leonard and David Pretel, ‘Experiments in Modernity: The Making of the Atlantic World Economy,’ in The Caribbean and the Atlantic World Economy. Circuits of Trade, Money and Knowledge, 1650-1914, eds A. B. Leonard and Daniel Pretel (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2015), 1–14. For a critique of this issue see: Maria Fusaro, ‘After Braudel: a Reassessment of Mediterranean History between the Northern Invasion and the Caravane Maritime,’ in Trade and Cultural Exchange in the Early Modern Mediterranean: Braudel’s Maritime Legacy, eds Maria Fusaro, Colin J Heywood, and Mohamed–Salah Omri (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 1–22 (2–3); Maria Christina Chatziioannou, On Merchants Agency and Capitalism in Eastern Mediterranean 1774-1914 (Istanbul: Isis Press, 2017); Eloy Martín Corrales, ‘Descolonizar y desnacionalizar la historiografía que se ocupa de las relaciones de Europa con los países del Magreb y Oriente próximo en la Edad Moderna (siglos XVI‐XVIII),’ RiMe. Rivista dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea 18 (2017): 163–93.

[23] Maria Fusaro, Political Economies of Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean: The Decline of Venice and the Rise of England (1450-1700) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[24] Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, 2 vols (New York: Harper & Row, 1972–1973), vol. 2, 1240–42.

[25] Abulafia, The Great Sea.

[26] David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. Why Some Are So Rich and Some Are So Poor (London: Abacus, 1998), 442–64.

[27] Important exception to this is the classic scholarship on the Iberian and Ottoman empires, which only recently is moving away from focussing exclusively on their economic decline in the early modern period.

[28] Benton herself argued that jurisdictional complexity was itself an interconnecting phenomenon in the early modern world in her Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[29] On this see the considerations of Seán Patrick Donlan and Dirk Heirbaut in ‘“A Patchwork of Accomodations”: European Legal Hybridity and Jurisdictional Complexity – An Introduction,’ in The Laws’ Many Bodies: Studies in Legal Hybridity and Jurisdictional Complexity, c. 1600–1900, eds Seán Patrick Donlan and Dirk Heirbaut (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2015), 9–34, and bibliography therein quoted.

[30] For an overview of these issues, from the perspective of political geography, see Philip E. Steinberg, ‘Lines of Division, Lines of Connection: Stewardship in the World Ocean,’ Geographical Review 89, no. 2 (1999): 254–64 and in general this monographic issue of the journal on the theme of ‘Oceans Connect.’ On English creative interpretations of the implication of this Treaty for American colonisation see Glyn Parry, ‘Mythologies of Empire and the Earliest English Diasporas,’ in Locating the English Diaspora, 1500-2010, eds Tanja Bueltmann, David T. Gleeson, and Donald M. MacRaild (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), 15–33 (18–19), and bibliography therein quoted.

[31] Seed, Ceremonies of possession; on this see the critical considerations in Benton and Straumann, ‘Acquiring Empire by Law,’ especially 19–20 and 31–32.

[32] Watkins, ‘The New Mediterranean Studies,’ 153. For a different view on Mediterranean connectivity and its contemporary ideological connotations see: Nabil Matar, ‘The “Mediterranean” through Arab Eyes in the Early Modern Period: From Rūmī to the “White In-Between Sea”,’ in The Making of the Modern Mediterranean: Views from the South, ed. Judith E. Tucker (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019), 16–35.

[33] For example, see: Lauren Benton and Adam Clulow, ‘Empires and Protection: Making Interpolity Law in the Early Modern World,’ Journal of Global History 12, no. 1 (2017): 74–92; further developed in Lauren Benton, Adam Clulow, and Bain Attwood, eds, Protection and Empire: A Global History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[34] Marglin, Across Legal Lines; Michael Talbot, British-Ottoman Relations, 1661-1807: Commerce and Diplomatic Practice in Eighteenth-Century Istanbul (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2017); Guillaume Calafat, Une mer jalousée. Contribution à l’histoire de la souveraineté (Méditerranée, xviie siècle) (Paris: Seuil, 2019), and the volumes in the Brill series ‘Mediterranean Reconfigurations,’ see: https://brill.com/view/serial/CMED?

language=en.

[35] ConfigMed – Mediterranean reconfigurations: Intercultural trade, commercial litigation, and jurisdictional pluralism ERC Advanced Grant, P.I. Wolfgang Kaiser, for more details see: http://configmed.hypotheses.org/.

[36] Wolfgang Kaiser, ‘A propos,’ ConfigMed – Mediterranean reconfigurations, last accessed 5 January 2020, http://configmed.hypotheses.org/a-propos-2.

[37] Kaiser and Petitjean, eds, Litigation and the Elements of Proof in the Mediterranean (16th-19th C.).

[38] The Making of Commercial Law: Common Practices and National Legal Rules from the Early Modern to the Modern Period, P.I. Heikki Pihlajamäki, last accessed 30 May 2023, http://blogs.helsinki.fi/makingcommerciallaw/presentation/.

[39] On the complex construct and definition of ‘Islamic law’ see: Ayesha S. Chaudhry, ‘Islamic Legal Studies: A Critical Historiography,’ in The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Law, eds Anver M. Emon and Rumee Ahmed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 5–44.

[40] Throughout the essay I am using the expression ‘legal system’ as this is the most commonly used, however, it is not quite precise and ‘body of law’ would be more appropriate. Nick Foster has pointed out how ‘one needs to distinguish between a body of law (e.g., English law), a legal system (a body of law plus the social phenomena which make it and make it work, e.g., the French legal system), a legal tradition (a set of legal systems with common historic and cultural origins, e.g., the Romano-Germanic legal tradition).’ Foster in a private communication with the author.

[41] For the history of this publication see Central Intelligence Agency, About The World Factbook — History, last accessed 25 May 2023, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/about/history/.

[42] Interesting to note, for example, that the United Kingdom is considered a single ‘administrative division,’ even though it is divided into three jurisdictions with their own legal systems. Interesting to note that the data on legal systems, which was accessible as a separate appendix until the 2020 edition, is not available anymore in a synthetic manner and this search needs to be done for each individual ‘administrative division.’ On the problems associated with the taxonomy of legal systems a very sophisticated analysis is: Mathias M. Siems, ‘Varieties of Legal Systems: Towards a New Global Taxonomy,’ Journal of Institutional Economics 12, no. 3 (2016): 579–602; see also Juriglobe. Groupe de recherche sur les systems juridiques dans le monde, last accessed 25 May 2023, http://www.juriglobe.ca/.

[43] On these issues is also relevant the concept of ‘Islamicate law,’ see Nandini Chatterjee, Negotiating Mughal Law: A Family of Landlords Across Three Indian Empires (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), especially chapter 1 and bibliography therein quoted.

[44] Antony Anghie, Imperialism, Sovereignty, and the Making of International Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007); Mark M. Mazower, No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009). For an analysis of these issues, especially on the relationship between Islamic legal history and contemporary political debates, see: Anver. M. Emon, ‘On Sovereignties in Islamic Legal History,’ in Middle East Law and Governance 4, no. 2–3 (2012): 265–305, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2146627 (last accessed 5 January 2020), and bibliography therein quoted.

[45] See Anver M. Emon, Religious Pluralism and Islamic Law: Dhimmis and Others in the Empire of Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); and Anver M. Emon, M. S. Ellis, and Benjamin Glahn, eds, Islamic Law and International Human Rights Law: Searching for Common Ground? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[46] On how the issue of ‘scale’ affects both methodology and analysis the essential starting place is Jacques Revel, ed., Jeux d’échelles. La micro-analyse à l’expérience (Paris: EHESS/Seuil, 1996).

[47] Interestingly, this is also an area where British professional historians have re-entered the public political debate with aggressive positioning, as evidenced by David Abulafia—possibly the foremost historian of the Mediterranean within the Anglophone world—chairing the nationalistic and conservative ‘Historians for Britain’ manifesto; on this debate see the analysis by Gideon Rachman, ‘Rival historians trade blows over Brexit,’ Financial Times, May 13, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/

86c8faa8-1696-11e6-9d98-00386a18e39d.

Maria Fusaro is Professor in Early Modern Social and Economy History at the University of Exeter, UK, where she directs the Centre for Maritime Historical Studies. She is the PI for the ERC-funded project 'AveTransRisk – Average – Transaction Costs and Risk Management during the First Globalization (Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries)'.

Cromohs (Cyber Review of Modern Historiography), ISSN 1123-7023

DOI: 10.36253/cromohs-14575

RECEIVED: 16 June 2023; PUBLISHED: 18 July 2023

© 2023 The Authors. This is an open access article published by Firenze University Press under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.