For a Fair(er) Global History

THE EUI GLOBAL HISTORY SEMINAR GROUP*

European University Institute, Florence

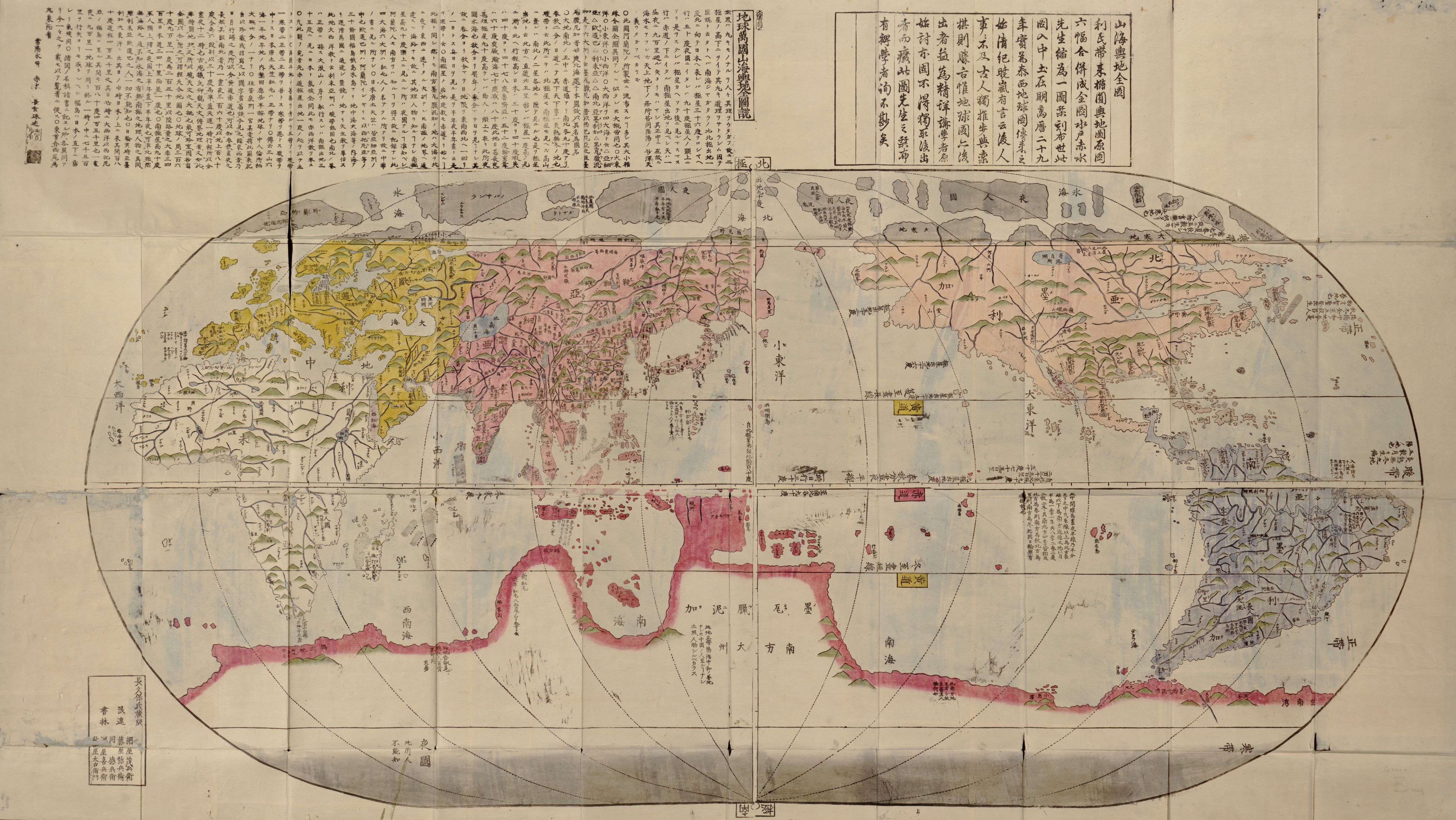

Sekisui Nagakubo after Matteo Ricci, Sankai Yochi Zenzu (山海輿地全圖) (Naniwa, 1785). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C.

In the Autumn of 2020, a group of us PhD researchers at the European University Institute (EUI) and two teachers met regularly as part of the PhD seminar in Global History. We were not all or always in the same room together, and often we stared at each other from tiny video-boxes that peeped into our living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens. Occasionally our internet connection would not bear the stress of the situation. This was a new connectivity of isolation, of sporadic quarantines, and of policed lockdowns. How to discuss global history in a world in which we could not meet, we could not shake hands, we could not visit friends and family; in which most of the places discussed looked more far away than they had ever been, surely in our lifetime?

What follows is the result of a conversation between twenty people – old and young, believers and not, charmed and repelled by global history. Over the course of ten, two-hourly seminars, we read and discussed a wide variety of texts that fall under the umbrella of global history. We started with prominent ‘state-of-the-art’ statements by Conrad (2016), Adelman (2017), and Berg (2013), among others. We then moved on to debates around ‘micro-global history’; ‘divergences’; ‘spaces’; the uses of digital public history and the issue of slavery. For those interested in finding out more about what we read, the seminar syllabus is available on the EUI website (EUI 2021a).

The vibrancy and freshness of the field was reflected in our regular discussions. In these discussions, we assumed no prior expertise; indeed, probably those seminar members who already explicitly identified as ‘global historians’ were in a minority. Most of us, including our teachers, sought different ways to incorporate a global history approach into research; we were interested in the methods and problems of global history, and we consciously challenged the boundaries of area studies by considering different times and places together, and by comparing different methodologies. We also note that the field has changed extremely rapidly over the last ten years or more, and it continues to do so. There is nothing canonical about global history: indeed, since its establishment in 2009, the EUI Global History seminar has altered so dramatically that not a single reading from the 2009 syllabus is on the syllabus for 2020 (EUI 2021b).

Based on our discussions, the two seminar teachers – Lucy Riall and Giorgio Riello – came up with a set of questions, to which PhD researchers gave individual answers. We then collated the answers, discussed the answers in a seminar, and we wrote them up and revised together the text which we present here. Ours is a deliberately collective effort of PhD researchers and teachers alike, an attempt at capturing not just the contours of global history; it is also a reflection of what we think global history might be, might become, or should be. We reflect on issues that confused and puzzled us, that made us angry and fuming mad. We did this together to show that global history cannot be done in isolation. We might have been alone in recent times, but our scholarly endeavour cannot be lonely.

We thank Cromohs for the opportunity given to us. We consider three topics: ‘The politics of global history’ thinking about global history as a form of activism; ‘Whose global history?’ considering issues of property and sharing; and ‘An open global history’ proposing a utopian future (for a troubled present).

The politics of global history

Once seen as the solution to a chronic lack of opportunities in history, global history has shown itself to be a disappointing answer, and surely no panacea for the ‘ills of history.’ Recent debates in global history – some of which have been conveyed in this very journal – do not entice anyone who might be considering joining the profession of history, let alone becoming a practitioner of global history. This sense of exclusion is due to a simple problem, one of centres and margins. Global historians are dismissive of Wallerstenian models of core and periphery but unwittingly they replicate these models over and over again. This is true of their scholarship as it is of their ‘social positioning.’ As a group of mostly young historians, we can debate whether we are on the ‘academic margin.’ We might – or not – have a career in history, find a job, or even complete a dissertation. Yet we are researchers at a rich (even with budget cuts) Western institution, a place that is not on the academic margin, though Florence might have been more a ‘global hub’ in the Renaissance than it is now.

Two months of reading and discussion on global history have left us all with a ‘bitter taste’ (l’amaro in bocca) and with the impression that competition rather than collaboration, gatekeeping rather than inclusion, dominate not just academic production but also academic debate in global history. Academia can be a nasty place, especially in elite institutions and – as we are all aware – competition has been a key principle of academic life (publish or perish; grants; H-indexes) for a while. There are some – certainly not all – esteemed researchers who have managed to build their own personal ivory tower quite high and with strong enforcements. In such a position, it is possible to select and project one’s voice with a sense of security. These people and these institutions act as broadcasters. They have become the centres of global history.

Not all historiographical trends emerge in elitist Anglophone centres of learning. Indeed, the origins of histoire culturelle, microstoria, and Alltagsgeschichte, as well as global history, lie outside the Anglosphere. However, it is now generally true that new historiographical currents do not become global phenomena unless they are recognised and assimilated by Anglophone centres and their respective publishing houses. At the same time, the identification of the ‘global’ with the ‘Anglosphere,’ and ‘Europe’ with its North-Western corner, reinforces a remarkably old-fashioned view of European history, more reminiscent of our nineteenth-century predecessors than of twenty-first-century scholarship. The fact that global history is travelling the same route into a more transnational, yet still traditional perspective is especially disappointing, as it runs against its own foundational objectives to de-centre master narratives and to make ‘the subaltern speak’ (Spivak 1993: 66–111). Global history has become global, and by doing so, has absorbed the zeitgeist of the present Anglophone age.

All of this is unacceptable because it is the emancipatory potential of global histories (the tracing of marginalised actors or the re-reading of conventional nation-state narratives) that makes it so interesting to so many people. So, if global history is in many ways a reflection of our globalised present, it can also show that this globalised world and its particular shape are not a given and that we (today) can shape our world as much as actors did in the past.

Our view of global history is not one of ‘a kind of history of all,’ nor do we seek to establish a new master narrative. We see global history instead as having a much-needed viewpoint: the panoramic has given way to more embedded perspectives. These are no longer solely interested in considering the local or the national, but they wish to provide new frameworks for the interpretation of global phenomena. They draw on local knowledge and local scholarship to build global interpretations that are both informed and incisive. This work is still done most frequently from the point of view of Europe and of the West more widely. Yet it could be equally done from the point of view of other places, other societies, and other scholarly communities. We feel that a global history written partly or primarily from the margins would foster a very different culture of debate. Yet, this is not just an aspiration. This wish can only happen through action. This is why we believe that global history has to work harder to address inequalities so that historians outside the United States and Europe can decide whether its lenses and scales of analysis are appropriate, suitable and fruitful.

If we were to propose a recommendation to our more senior global historians, it would be to build a truly multipolar and multilingual academic network, in which more scholars could feel that they have something to contribute. To do so means being open about the fact that the present structure of international academia incorporates hierarchies of dominance and sometimes oppression. This admission, in turn, leads to broader questions about inequalities amongst institutions dedicated to knowledge creation, and within and among the states and societies, globally and locally, that fund and support these institutions.

Power is everywhere and it is not equally distributed. Yet there are forms of power that are not even perceived as such. During our seminar series we discussed the role of language and in particular of the English language. All our readings were in English; yet for the vast majority of us this was not our mother tongue. We asked a paradoxical question: if English disappeared as academia’s international lingua franca, what would happen to the existing hierarchies of knowledge production? What would global history look like? Global historian Martin Dusinberre (2017) attempts to grant more importance to local languages and put at the core of the narrative people and actors that would otherwise tend to be invisible or ignored in grand narratives. His article in The History Workshop Journal displaces the certainties of Western academia by having us all confront documents in their original language. Even if incomprehensible to most of us (though not all), a passage in Japanese might be more truthful to the subject considered than some ventriloquising in English.

Multilingualism can help access not only different documents, but also different worlds and perspectives. These might be those of historians that do not belong to the Anglosphere. Rather than translate Anglophone global history books into other languages, one might wish to translate works in Chinese, Japanese, but also Spanish, Italian, and French into many languages, among which English. This requires some serious rethinking on how and what to publish, and by whom.

The most prestigious publishers – once again UK and North American academic presses and prominent commercial ones – have ridden the wave of global history to produce scholarly as well as popular books aimed at a broader public, written by established (predominately male) scholars in prominent universities. In doing so they have once again confirmed established hierarchies and taken away the disruptive potential of global history. The fact that global history’s main journals are to be accessed through subscription limits their impact outside a dwindling number of (mostly Western) institutions who can afford to subscribe to them. Here the problem is not just about publishing in, let’s say, the Journal of Global History – a Cambridge University Press journal – but the fact that if the article is not open access, it won’t be easily consultable by scholars in ‘poorer’ institutions. The gap can only widen.

Perhaps global history should set a new agenda, a programme of inclusion for a plurality of perspectives, becoming a forum of discourse, creating a space of safety, where voices of the previously (or maybe still) unheard and silenced might find a place to speak. Historians and writers from the margins of the Anglosphere should not only be included in some of the already existing debates in global history: they should also have their say when it comes to establishing the questions and debates. A generation ago this was the case for women historians: in a field still dominated by men, it was acknowledged the role that women played in opening entirely new fields of historical enquiry. Global history has the responsibility of bringing forward a new important shift to revise the inclusivity of history. Perhaps the agenda of global history should include ‘proactive listening.’ Through acknowledging and considering the universality of difference, a wider (but probably still incomplete!) history of our worlds might find the space to emerge.

Whose global history?

In a much cited and thought-provoking online article, Jeremy Adelman asked us all to think about those who are left out in global histories: his point of reference was the vast number of people who do not travel, who are not connected and whose experience of the global is mostly shaped by the nefarious consequences of globalisation (Aldeman 2017). These people might not feel the sense of empathy for global history that university professors have. Adelman had in mind America’s Rust Belt working classes, rather than a peasant in Nigeria or a factory worker in Jiangsu. In the making of global histories one has to ask who they might be for? National histories served – for good or bad – nation building. They shaped a sense of national identity (and sometime nationalism); they celebrated (or glorified) a country’s institutions and culture; and they served to create a sense of purpose (and self-imposed limits) in historical narratives. All of these ‘coordinates’ are difficult to plot on a global map. To say that global histories serve to create a ‘global identity’ or celebrate supranational institutions or culture would be disingenuous.

What global history has done effectively is to respond to Dipesh Chakrabarty’s call to ‘provincialize Europe’ (Chakrabarty 2000). Today no historian would consider the world as composed of a collection of mere receptors that accept the ideas and institutions developed and established in the ‘centre’ (i.e. the West). Yet this project is anything but easy and automatic. After several years of success for global history in certain academic contexts, historians have been able to broaden their topics, their geographies, their tools and the scope of their studies. And yet, one cannot help but think that global history is somehow similar to Western public opinion as shaped by mass media: they both pretend to encompass distant geographies, and yet in their narrative some figures (such as ‘great men’) and some places are far more important than others (with entire countries or even continents disappearing in the background). As Maxine Berg has remarked, in the process of converting Europe from ‘knowing subject’ to ‘an object of global history,’ we have moved merely from Eurocentrism to ‘a Eurasian centrism’ (Berg 2013: 5). Integrating the Global South – Africa, Iberian America and the (non-Anglo) Pacific Ocean – into global historiography remains a challenge, in part because academic hierarchies can work implicitly to exclude voices and methodologies that are different from their own.

Hence, ‘unevenness’ turns out to exclude as much as it tries to include. Perhaps this is an inbuilt limitation of global history: in its tireless attempt at embracing larger geographies, and chronologies, it has to admit that many people (past and present) will not fit within their narratives and that their stories will not be relevant to the vast majority of the 7.7 billion people on earth. Here one has not to fall into the trap of thinking of a kind of universal history that fits all. If there is one message to bring home after ten weeks of readings in global history, it is that the field is varied, multifarious, and at points cacophonic. Our point here is that these qualities can only be cherished, valued and promoted. Attempts at explaining ‘what are global histories’ have a tendency of providing totalizing answers that do not sufficiently reflect either on who writes such histories, nor who they are for.

What if one starts writing a global history departing from, say, a Southeast-Asian Studies department in Singapore? What happens when South American history departments in Buenos Aires or Lima start writing globally? The first and foremost thing is that such departments are filled with people who know the languages and who might bring perspectives and methodologies that are different from colleagues based in Europe or North America. To take another example: what if intellectuals from India start resisting the global narrative of European superiority? This, of course, has already happened with the emergence of subaltern studies. One might expect global histories that are equally analytical and deconstructionist as seen in the work of members of this intellectual circle (ironically, however, quite a few of these intellectuals ended up at the Ivy League universities).

Another outcome would be that the agency of non-European actors in history will be much better understood. Yet, historians of Europe and the West might object that all of this has little to do with them. For all those who think that European histories cannot but be by default Eurocentric, a problem remains on how to access – one might say ‘calibrate’ – European hegemonic power. It is a topic that surely affects global and imperial histories, but in recent years its presence has been acknowledged also in continental and national histories. In our readings, we discussed the role of European actors in changing global environments, in exploiting resources, transforming landscapes and disrupting ecosystems. These are topics that resonate with early-career scholars and inform research projects at the EUI and elsewhere. They raise difficult questions about agency, subjectivity, power, and the role of humans in Anthropocenic histories. They also create new histories that are no longer about ‘us vs. them,’ or ‘the West vs. the Rest’ but consider the complex links between actors, environments and institutions within a global canvass.

An open global history

In the mid-twentieth century, scholars from the Annales school in France and Marxist historians based in Britain sought to change the subjects, temporalities and categories of history. ‘I am seeking,’ E. P. Thompson wrote in the preface to his classic work, The Making of the English Working Class, ‘to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the “obsolete” hand-loom weaver, the “Utopian” artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity’ (Thompson 1980: 12). Yet this attempt to write a history ‘from below,’ and the inclusion of the category of class into the writing of history, ended by marginalizing many: women, notably, and among and along with women the racialised ‘subaltern’ and the non-normative ‘deviant,’ as well as anyone whose primary identity was not defined by the hierarchy of class. Marxist historians’ focus on the agency of class relegated subjectivity to a secondary role; the working-class man’s identity was defined by his social position, not by his self-understanding.

The point is that we have been here before. All linear narratives, including historical ones (‘The making of’), are built around a central protagonist and scenario – whether hero, class, movement or country – so that any attempt to rescue past outsiders from ‘the condescension of posterity’ must inevitably banish others to the periphery. This is not to say that a focus on outsiders or a shift in temporality cannot alter the narrative – this is exactly what the Annales and Marxist historians did achieve – but rather to challenge the idea of a linear narrative of ‘before’ and ‘after,’ especially when it comes to global history (Seigel 2004). In our seminar discussions, we returned again and again to the importance of subjective experience, to a history ‘from below’ that could include subjects and locations in a minor key, and a history that might pay attention to the plurality of voices rather than simply to those who seem to speak the loudest. Equally, this emphasis on subjectivity implies a degree of humility and consideration, among and between global historians, about who we are, what we do and the limits of our understanding as a profession.

This is not to say that a global approach to history can teach us nothing new. To the contrary. The plethora of voices; the variety of subjects; the stakes of the debate: all this is inspirational and challenging in a discipline that relies so heavily on experience, practice, common understanding and a received style in written language. If nothing else, the readings have forced us to confront our inherent privilege, our own complicity as practitioners and beneficiaries of the Western master narrative. We were in broad agreement about a collective and productive ‘loss of innocence’ that is brought about by the study of global history.

What have we learnt from these readings and discussions, and how might a future global history fulfil its original, emancipatory potential? We each have our own ideas, but below are listed a few suggestions and comments as expressed by members of the seminar:

- More global history about and by women. Given global history’s emphasis on different people and new places, it is surprising (ironic?) that this is such a male field. The male voice and gaze tend to dominate in debates, and men tend to be more visible protagonists of global historical narratives. There is some excellent global women’s history but it is separate from broader discussions about space, connectivity and mobility.

- Equally, the emphasis on transnational ‘connectivity’ tends to privilege those with the time and money to connect. With some exceptions (Amy Stanley’s Japanese ‘maidservants’ tales’ comes to mind) we know little about the experiences of those ‘disconnected’ by the global, or the global visions and experiences of those who stayed at home (Stanley 2016).

- The plurality of processes of knowledge construction. Global histories have the potential vastly to enlarge the analysis of the ways in which people in the past as in the present made sense of their natural and social environments. These histories are environmentally aware and consider the relationship between humans, nature, material things (resources, technologies, tools, artefacts, consumer goods), and cross-cultural practices.

- The need to de-centre more than Europe. It is not sufficient to add more places and examine the connections between different spaces. ‘Eurasian-centrism’ does little to displace the categories of progress and modernity, or the presence and lack thereof (the question of ‘divergence’), that still lurk within narratives of global history. ‘Reciprocal comparisons’ that start with Nigerians, Peruvians or the Japanese and use their experiences to ask questions of European history may offer a way forward (Austin 2007).

- The need for more complex storytelling, that develops different relationships between present and the past. We do not learn ‘lessons from history’ but historians can identify alternatives and turning points, and they can account for the unexpected. With regard to twenty-first-century concerns, global history could serve to ‘de-nationalize,’ and hence help to explain, the history of slavery. A global approach to the history of slavery would contextualize the specifics of slavery in the United States; allow us to explore the conjunctures between slavery and race; and identify the relationship between slavery, on the one hand, and the history of colonial conquest, on the other.

- Among the best, or most innovative, work that we read in the seminar were topics from early modern global historiography. As has now become almost customary, we stretched the early modern moniker well into the nineteenth century; it is also worth noting that twentieth-century global history has a distinct institutional and international focus, and that we have a separate EUI seminar that covers this period. This question of chronological periodisation is important. Surely there is nothing more Eurocentric than the division into medieval, early modern, modern etc. Does this work anywhere other than Europe? Does it even work in Europe? Valerie Hansen has shown that if we start the ‘global’ in 1500 with what used to be called the ‘Age of Discovery,’ we also necessarily centre Europeans; we exclude the consideration that in their discovery of ‘new’ worlds, Europeans followed routes established by non-Europeans several centuries before (Hansen 2020). We need critically to address that Europe works ‘as a silent referent’ also in questions of how change occurs over time (Chakrabarty 2000: 28).

We repeat our thanks to Cromohs for the chance to express our views in this collective format. Seminars and teaching have been hugely affected by COVID-19, and we will be happy if our experiences of, and reactions to, the problems facing global history during these unsettling times can stimulate further discussion. In particular, we welcome Cromohs’s commitment to open-access publishing. It is only through the free and full exchange of scholarly ideas and research that we can hope to advance this exciting field of study.

References

Aldeman 2017: Jeremy Adelman, ‘What is Global History Now?’ Aeon, Essays, March 2, 2017, https://aeon.co/essays/is-global-history-still-possible-or-has-it-had-its-moment.

Austin 2007: Gareth Austin, ‘Reciprocal Comparison and African History: Tackling Conceptual Eurocentrism in the Study of Africa’s Economic Past,’ African Studies Review 50, no. 3 (2007): 1–28.

Berg 2013: Maxine Berg, ‘Global History: Approaches and New Directions’ and ‘Panel Discussion: Ways Forward and Major Challenges’, in Maxine Berg, ed., Writing the History of the Global: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (London: Published for The British Academy by Oxford University Press, 2013), 1–18, 197–208;

Chakrabarty 2000: Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Conrad 2016: Sebastian Conrad, What is Global History? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016)

Dusinberre 2017: Martin Dusinberre, ‘Japan, Global History, and the Great Silence,’ History Workshop Journal 83, no. 1 (2017): 130–150.

EUI 2021a: European University Institute, Department of History and Civilization, Research & Teaching, Seminars, 2020-2021 1st term, Global History, Accessed January 31, 2021, https://www.eui.eu/DepartmentsAndCentres/HistoryAndCivilization/ResearchAndTeaching/Seminars/2020-2021-1st-term/DS-Global-History-RiallRiello.

EUI 2021b: European University Institute, Department of History and Civilization, Research & Teaching, Seminars, Past Seminars, Accessed January 31, 2021, https://www.eui.eu/DepartmentsAndCentres/HistoryAndCivilization/ResearchAndTeaching/Seminars/Past-Seminars.

Hansen 2020: Valerie Hansen, The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World and Globalization Began (New York: Scribner, 2020).

Seigel 2004: Micol Seigel, ‘World History’s Narrative Problem,’ Hispanic American Historical Review 84, no. 3 (2004): 431–446.

Spivak 1993: Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ in Laura Chrisman and Patrick Williams, eds, Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 66–111.

Stanley 2016: Amy Stanley, ‘Maidservants’ Tales: Narrating Domestic and Global History in Eurasia, 1600–1900,’ American Historical Review 121, no. 2 (2016): 437–460.

Thompson 1980: Edward P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, new ed. (London: Gollancz, 1980), 12.

The EUI Global History Seminar Group - Friedrich Ammermann (Germany), Paul Barrett (Ireland), Lucile Boucher (France), Olga Byrska (Poland), Elisa Chazal (France), Vigdis Andrea Baugstø Evang (Norway), Eoghan Christopher Hussey (Ireland), Carlos Jorge Martins (Portugal), Roberto Larrañaga Domínguez (Spain), Fartun Mohamed (Italy), Sven Mörsdorf (Germany), Bastiaan Nugteren (The Netherlands), Anna Orinsky (Germany), Rebecca Orr (United Kingdom), Cosimo Pantaleoni (France), Lucy Riall (Ireland), Giorgio Riello (Italy and United Kingdom), Asensio Robles Lopez (Spain), Alejandro Salamanca Rodríguez (Spain), Liu Shi (China), Takuya Shimada (Japan), Halit Simen (Turkey).

Cromohs (Cyber Review of Modern Historiography), ISSN 1123-7023

DOI: 10.36253/cromohs-12559

RECEIVED: 20 January 2021; PUBLISHED: 03 February 2021

© 2021 The Authors. This is an open access article published by Firenze University Press under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.