Edmund Burke, the Atlantic American war

and the ‘poor Jews at St. Eustatius’. Empire and the law of nations

Università di Trieste

This essay is devoted to a relatively minor episode in Edmund Burke’s parliamentary career and political speculation involving the rights of war and international law in the final years of the American War of Independence. The starting point for Burke’s consideration of these questions was the affair of St. Eustatius, that is to say Britain’s conquest in 1781 of the Dutch West-Indian island early in the “fourth Anglo-Dutch War” of 1780-1784. The harsh treatment of the Dutch colony’s cosmopolitan community by the commanding officers of the British Navy and Army provoked a series of reactions in Britain and the colonies. The essay starts by outlining the identity of St. Eustatius with its economic, demographic and social features, its peculiar role in the eighteenth-century West Indies and its emblematic meaning in the historical literature of the Enlightenment as a symbol of the virtues of commerce and of economic liberty. It goes on to analyse the facts of the military conquest in 1781 and the ensuing occupation realized by Admiral George Rodney and Major-General John Vaughan, particularly as this affected the “poor Jews at St. Eustatius” (as Burke himself qualified them in his second speech on 4 December 1781), with the subsequent reactions of the Dutch and especially the British Atlantic world. We then examine Edmund Burke’s reasons for taking up this affair, including the political and ideological motives and the sources of arguments he used in the two parliamentary speeches he made on the topic during 1781, relating this to Burke’s ideas on international relations and imperial government during the 1770s and 1780s. We end by pointing to cultural links between Burke’s positions and a wider political, commercial and civic culture emerging in the British Atlantic world which reflected some of the most typical European Enlightenment values and ideological commitments.

1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | Notes

1.

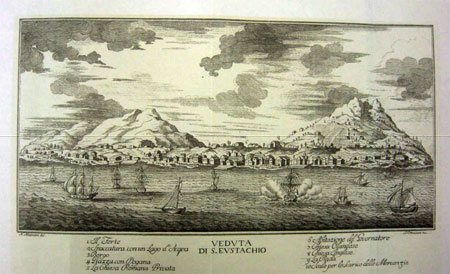

1. Let us try to conjure up the scene as it presented itself one February day in 1781. Longitude 62.56 West, latitude 17.29 North. Intense sunlight, the Caribbean and “that small speck in the ocean”[1]: an island with two peaks – one volcanic in origin – rearing up at its east and west ends, the slopes covered in lush vegetation, separated by a fertile valley covered in plantations and cultivated fields, descending to a low-lying coastal strip (see fig. 2). This is St. Eustatius, a Dutch possession since 1636 in spite of various vicissitudes, governed by the Dutch West India Company. A single town – Oranjestad – is set back from the only landing place on the island, watched over by a fortress with batteries of cannon and a flagstaff sporting the colours of the United Provinces. This would have been the sight that greeted the French Dominican missionary Jean Baptiste Labat, author of the Nouveau voyage aux îles de l’Amérique (1722), who was able to observe it at close quarters, although without going ashore, in 1705.

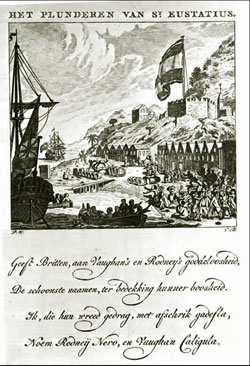

2. We can get a better idea of what happened on that Tuesday 13 February 1781 with the help of a contemporary print (see fig. 1)[2]. On the beach in front of a line of houses, built Dutch style abutting each other, lie piles of merchandise, bales, sacks and rows of barrels. Two boats are heading out to a ship flying the Union Jack, carrying people who are waving to those left on land. On the shore a group of distraught men and women are stretching their arms out towards the people in the boat, who appear to be leaving unwillingly, or indeed are being deported. Reduced to tears, they make gestures of desperate entreaty to the British troops presiding over the scene, the famous “lobster backs” or Royal Marines. Further off another small group are standing by helplessly, probably under restraint, while in the houses and along the beach perquisitions are taking place and merchandise is being stockpiled. Some of the figures are being manhandled by the soldiers while others seem to be protesting. We can imagine the rest of the scene, although it is not depicted. British officers, with inflexible efficiency, are making sure that the people in the boats – we know them to be thirty or so heads of families taken from among the Jewish residents on the island, the group who became known as the “poor Jews at St. Eustatius” – are duly embarked on the ship that is to take them into exile on one of the numerous islands nearby, separating them from their wives, children and elders. Then the troops go back into the town. We know that the Jews who were left behind, after being subjected to brutal searches, were locked up for three days and released just in time to see all their property being sold off at auction. This was one of the most tragic and controversial moments of the “plunder of St. Eustatius”, as it is referred to in the print caption. Ten days previously, at 3.30 pm on 3 February 1781, some frigates of the Royal Navy had appeared in front of the tiny but prosperous Dutch island and demanded its unconditional surrender, which was immediately conceded. An occupying force was put on shore and literally “took possession”, sealing off warehouses, shops and offices, searching houses, seizing financial records, confiscating property, stores and shipments and stripping the inhabitants of all their possessions: part of the booty was sent back to England, and the rest sold of at auction shortly afterwards.

3. This is a very brief account of the little known events that took place at the beginning of 1781 on the minor Caribbean island of St. Eustatius (in Dutch Sint Eustatius, but also Statia, Eustatia and St. Eustatia), the starting-point for this essay. We intend to investigate this episode and give fuller details, not so much for the light it throws on the history of Dutch trade in the Antilles or on the history, rich and compelling though this is, of the Jewish communities in the West Indies, but because it prompted two speeches in the House of Commons by Edmund Burke. While these speeches had their political and parliamentary motivations, they were resonant with considerations on the theme of the law of nations and empire and undoubtedly stand out for their noble, liberal and, we may confidently say, enlightened stature. A proper appraisal of the positions that Burke took on this affair is indispensable in reconstructing the structure, complexity and originality of his political speculation as he strove to combine the dimension of an Imperial power with the universal values of jurisprudence, reason and justice. First of all, however, we have to provide an outline of the overall historical context[3].

Picture 1. “The plunder of St. Eustatius”, Atlas van Stolk Collection, Rotterdam. The caption reads: “Great Britain lauds the enormities of Rodney and Vaughan in the most fulsome terms to conceal their iniquity. I, for my part, filled with horror at their cruel behaviour, call Rodney Nero and Vaughan Caligula”.

2.

4. The American War of Independence was in full swing, with France and Spain having entered on the side of the Americans in 1778. After Saratoga (October 1777), Great Britain adopted the so-called “strategy of the South”. It concentrated its military actions in the more loyalist southern colonies, conquering Georgia and South Carolina, penetrating into North Carolina and rashly pushing on into Virginia. But it did not manage to achieve the hoped-for master blow. Cornwallis was obliged to make a stand at Yorktown, in Chesapeake Bay, within range of French naval forces. Joint action by the fleets of d’Estaing and Barras together with that under de Grasse, arriving from the West Indies, enabled the troops led by Rochambeau and Washington to lay siege to the British forces at Yorktown in October 1781 and force a surrender. We can note – and will return to the subject – the important role played by the fleet of de Grasse, which arrived providentially from the Caribbean to provide transport for the Franco-American troops in the area of hostilities and keep a British naval force despatched from New York out of the action. However, let us go back a few months, to when the theatre of war was located in the West Indies.

5. On 20 December 1780 Great Britain declared war on Holland and ordered its ambassador Sir Joseph Yorke (1724-1792) to leave The Hague, bringing to an end an ambiguous period of Dutch neutrality. In September of that year Holland had adhered to the League of Armed Neutrality, sponsored by Catherine II of Russia in February 1780 with the participation of Prussia, Denmark, Sweden, Portugal, the Reign of Naples and some more European countries with the aim of guaranteeing freedom to trade for neutral states, except in the case of illicit conveyance of military and naval supplies[4]. The “fourth Anglo-Dutch War” (1780-1784) was the logical outcome of the inexorable deterioration in relationships between Great Britain and Holland, above all after the commencement of secret negotiations in 1778 between the “regenten” in Amsterdam and the American ambassadors in Paris, Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee, over the provision of economic and financial aid by the Dutch to the colonial rebels. The secret had come out in September 1780 when a British frigate had intercepted an American ship bearing the Carolina statesman Henry Laurens (1724-1792), a former president of Congress and currently United States commissioner in Holland. He was carrying a copy of the 1778 agreement and subsequent correspondence paving the way for a treaty of mutual assistance and trade, as well as a loan[5]. The Dutch and Americans had been increasingly linked in a network of commercial relations in which the Caribbean played a crucial role, and St. Eustatius was the nerve centre of the Dutch Antilles.

Picture 2. Aerial photograph of St. Eustatius today (source: Google Earth)

6. For at least a couple of centuries, and in this period more than ever, the seas of the West Indies had seen continuous encounters, attacks, skirmishes and pursuits, in times of peace and war alike, involving the vessels of six or seven different nations, whether ships of the line and privateers or merchant fleets with their escorts and pirate ships of every shape and size. These were thus particularly hazardous waters, the scenario for an intense traffic in smuggled goods, in flagrant violation of the protectionist legislations upheld by all the European nations active in the area. The reality of economic and social history in the Atlantic cannot be circumscribed to the data and histories of the individual nations, for it involved a complex tangle of interests. The rich island of St. Eustatius had long enjoyed, and continued to enjoy in spite of repeated protests on the part of the British government, a prime role in this far-flung trading network, on account of having been made a free port in 1753.

7. Known also by the alluring nickname of “the golden rock”, this volcanic outcrop is one of the Sopravento islands forming part of the Dutch Antilles, along with St Maarten, Saba, Curaçao and Bonaire. It was occupied in 1635 and, in spite of its unpromising aspect, gradually turned to some account by the Dutch, “who were the only people in the world who could have rendered so unpromising a spot a flourishing settlement”[6]. In the course of time, under the control of the Dutch West India Company and in particular the Zeeland Chamber, which exercised the right of patronage on local offices, the favourable conditions provided by the lack of commercial regulation and tax and customs duties ensured a burgeoning economy, due also to its strategic geographical position and its natural features, making it one of the most frequented ports in the Caribbean. Not far off there lay, to the east, St. Barthélémy, which was French, to the north St. Croix, Danish (now part of the American Virgin Islands) and Puerto Rico, Spanish; to the south Antigua, St. Christopher (or St. Kitts) and Nevis, all British, and Guadeloupe and Martinique, French. The wealth of St. Eustatius thus derived not so much from the limited production of sugar, tobacco, cotton and indigo but essentially from goods in transit, from trade in smuggled goods of every kind and provenance, and from the refinement of the sugar cane brought here from the neighbouring British and French islands.

Picture 3. View of the island of St. Eustatius, drawn by Nicola Matraini, engraved by Giovanni Ottaviani, in Il Gazzettiere Americano, Livorno, Coltellini, 1763, vol. I, between pp. 188 & 189

8. We have a strikingly direct and evocative record of conditions on St. Eustatius in the mid-1780s in the journal of the Scots lady Janet Schaw, who made a long voyage through the West Indies and into North Carolina, during which she visited several of the British islands, such as Antigua and St. Christopher, and the Dutch St. Eustatius[7]. “A place of vast traffick from every quarter of the globe,” she called it when she landed here in the autumn of 1774. It was not a beautiful island, in her opinion, nor somewhere she would have wished to live, but nonetheless an extraordinary “instance of Dutch industry”. Its true wealth consisted not in the products of the land but in the incredible variety of smuggled goods which it exchanged with nearby islands for staple goods. The town was small, with a single road running through it, perhaps a mile long, crowded with people speaking in a variety of languages, each arrayed in their own national dress and smoking tobacco incessantly. For someone whose only experience of Jewish dress had been the actor Diggs impersonating Shylock, she manifested extreme curiosity on finding herself confronted by a “set of Jews”. This turned to pangs of commiseration when she heard accounts of the horrible “Christian cruelty” some of them had suffered at the hands of the Inquisition in their native lands before arriving on St. Eustatius, where they had finally found a welcome and humane treatment. But as one might imagine, what made the greatest impression on this Scottish milady, with her unerring instinct for advantageous terms for French gloves, English stockings, pickled vegetables, tinned meats, excellent claret and assorted Portuguese wines, was the assortment of merchandise of every description and quality:

From one end of the town of Eustatia to the other is a continued mart, where goods of the most different uses and qualities are displayed before the shop-doors [...] rich embroideries, painted silks, flowered Muslins, with all the manufacture of the Indies [...] jackets, trousers, shoes, hats [...] most exquisite silver plate, the most beautiful indeed I ever saw and close by these iron-pots, kettles and shovels [...] French and English Millinary-wares. But it were endless to enumerate the variety of merchandize in such a place, for in every store you find every thing, be their qualities ever so opposite.

9. One thing that Janet Schaw omits to comment on, however, was the degree to which the island’s prosperity depended on the slave trade. Run by the Dutch West India Company and private traders, above all British, and in existence since the second half of the 17th century, this not only met the needs of the local sugar and tobacco plantations but provided labour for the neighbouring British, French and Spanish island colonies (naturally outside the provisions of the assiento). At its height, at the turn of the 18th century, some 2-3000 slaves were shipped to the island each year directly from Africa. Slaves even became a sort of currency for the merchandise, above all sugar and its derivatives, which was brought to St. Eustatius from all over the Caribbean and sent on from here above all to North America. Nonetheless it is true that by the middle of the 18th century trading in slaves had begun to decline on the island, being definitively prohibited in 1784, although the coloured population was almost always in the majority.

10. At the time of the events that interest us, and bearing in mind that available estimates are not unanimous but nonetheless give a more reliable picture than the exaggerated figures given in contemporary accounts, St. Eustatius numbered some 3295 inhabitants, of whom 1574 white and 1631 coloured slaves (in 1790 the total rose to 7830, with 4944 coloured slaves and 511 freed slaves)[8]. The non-African population was made up above all of merchants of different nationalities – Dutch, French, British, Spanish, American, Turkish, Greek, Levantine – and by a predominantly Sephardic Jewish community drawn from all over Europe and America, which was quite numerous although not as large as the one on Curaçao[9]. We can identify two significant demographic and socio-economic phenomena in the first half of the 18th century: the island’s increasing Anglicization, due to the ever greater presence of British merchants[10], and the growth of the Jewish community. From 1730 there had been a steady flux of Jewish immigration, particularly from Amsterdam. As the community grew the congregation of Honem Dalim was founded and at least partial equality with the Christians was achieved through the intervention of the parnassim of Amsterdam[11], while the support of brethren in Amsterdam and Curaçao made it possible to build a synagogue. Inaugurated in 1739, the remains of the building were recently restored. In 1781 the resident Jews numbered perhaps 350 in all, with 101 adult males. The road off St. Eustatius was very busy, on account of the trading benefits and custom franchises. The statistics we have indicate that the island was visited by somewhere between 1800 and 2700 ships each year, with the highest tally being 3551 in 1779. Thus this was a rich and dynamic emporium, at the confluence of trading routes from all over Europe, Africa and North America. The traffic passing through could not possibly be regulated by the prohibitionist legislation in force, and it was particularly profitable for the Dutch, who acted as transporters, brokers and fixers for all the other nations. Admiral Rodney was understandably exultant in a letter to his wife soon after his conquest: “the riches of St. Eustatius are beyond all comprehension [...] the capture is prodigious”[12]. In fact the island was remarkable not only for its thriving mercantile economy but also as a typically cosmopolitan society combining all manner of ethnic groups, languages and religions. It was tolerant, composite in every respect, and a lure both for honest merchants and the scum of every nation of Europe alike.

11. It was Edmund Burke who gave the House of Commons an effective thumbnail sketch of the island, detailing its natural, economic and social characteristics in terms that bear out what we have described so far:

This island was different from all others. It seemed to have been shot up from the ocean by some convulsion; the chimney of a volcano, rocky and barren. It had no produce [...] It seemed to be but a late production of nature, a sort of lusus naturae, hastily framed, neither shapen nor organized, and differing in qualities from all other. Its proprietors had, in the spirit of commerce, made it an emporium for all the world; a mart, a magazine for all the nations of the earth [...] Its wealth was prodigious, arising from its industry, and the nature of its commerce[13].

Prior to the events that set it firmly in the limelight, to gain an idea of the island public opinion in Europe had to rely on the information contained in volume XV of the Histoire générale des voyages (1759). Rather more details could be obtained from the well known American Gazetteer (1762) (see fig. 3), while a particular perspective was offered by the most celebrated contemporary world history of European colonial trade and settlements, Raynal’s Histoire des Deux Indes[14].

12. The latter is of chief interest for us in showing, as one might imagine, how the particular conditions of St. Eustatius led to its inclusion in considerations on the freedom of exchanges and the doux commerce dear to the Enlightenment. In Book XII Chapter XVII of the Histoire des Deux Indes (1770), Raynal presented a succinct and far from alluring image of “St. Eustache”, while shortly afterwards, in Chapter XX, his ideological intent becomes quite explicit. This island, impregnable even to the “ennemi le plus audacieux”, if only it is defended “avec vigueur et intelligence”[15], became in these pages a minuscule but highly effective symbol of the economic energies which, even with the illegal but beneficial assistance of contraband, could prevail not only over the “joug odieux du monopole”, which weighed heavily on the neighbouring islands, but also over the warring spirits that divided nation from nation. Indicated by Raynal as the general emporium of the French Antilles, during the Seven Years War merchants from a variety of nations met up with one another in its roadstead, under the warranty of freedom of access granted to one and all, irrespective of country of origin: “De cette grande liberté naissent des opérations sans nombre & d’une combinaison singulière. C’est ainsi que le commerce a trouvé l’art d’endormir & de tromper la discorde”[16].

We find a similar image in the Wealth of Nations (1776), where Smith emphasises with his customary pithiness the fecundity of free trade as opposed to the sterility of nature to be found there:

Curacoa and Eustatia, the two principal islands belonging to the Dutch, are free ports open to the ships of all nations; and this freedom, in the midst of better colonies whose ports are open to those of one nation only, has been the great cause of the prosperity of those two barren islands[17].

Likewise for Adam Anderson, historian of trade, the island stood as tangible proof of how, in a condition of liberty, profitable commerce could thrive even in conditions of natural sterility or indeed warfare:

barren and contemptible in itself [St. Eustatius] had long been the seat of a very great and lucrative commerce and might indeed be considered the grand free port of the West Indies and America and as a general magazine to all nations. Its richest harvests were however during the seasons of warfare among its neighbours in consequence of its neutral state and situation with an unbounded as well as unrestrained freedom of trade[18].

13. Thus Burke found himself in good company when in his speeches to parliament he insisted on the commercial virtues of St. Eustatius, on the disregard of its inhabitants with respect to fortifications, and on the lack of strategic or military goals behind the conduct of the Dutch. And he would surely have subscribed to Raynal’s appraisal of this conduct: “également inventif dans les moyens de faire tourner à son avantage le bien & le mal d’autrui”. In a nutshell, this little island symbolised to perfection the virtues of pacific commerce: in the words of the Irish statesman, it was a latter-day Tyre, whose mercantile vocation was however at odds with the raison d’état and power politics[19].

14. The situation of St. Eustatius proved to be particularly favourable – and a real thorn in the side for Great Britain – on the outbreak of war with the North American colonies. All necessary provisions continued to reach the colonies through the emporium of St. Eustatius, supplied not only by enemy and neutral nations but also by British merchants working out of the homeland and the British Antilles[20]: after all, contraband by definition recognises no national boundaries. On the basis above all of the correspondence between London and the ambassador in The Hague, Sir Joseph Yorke, J. Franklin Jameson has shown the fundamental importance of St. Eustatius in the economics of the American revolution, serving as both a market for the colonists’ exports and as a source of supplies which proved invaluable when Britain imposed first a boycott and then a total embargo on imports[21]. Naturally for St. Eustatius, like Curaçao[22], the situation brought great benefits, and from 1774 the volume of trade began to expand enormously, reflected in a striking prosperity. The presence of American merchants, although not a novelty, became constant, in spite of Sir Joseph Yorke’s official protests to the States-General [23]. Such activity was not in fact restricted to St. Eustatius, and when Great Britain went onto the offensive in the Caribbean its targets included other Dutch islands and colonies like St. Maarten and Saba, as well as the ports of Essequibo and Demerara on the Southern American coast. “The golden rock” was only the richest and most important of a small constellation of legal and illegal trading posts and markets. This is made explicit in the manifesto published by Great Britain on 20 December 1780 setting out the reasons for declaring war on Holland:

In the West Indies, particularly at St. Eustatius, every protection and assistance has been given to our rebellious subjects. Their privateers are openly received in the Dutch harbours; allowed to refit there, supplied with arms and ammunition, their crews recruited, their prizes brought in and sold[24].

15. There is no doubt that there were bones of contention between Great Britain and Holland connected with the conduct of international trading activities outside the Central American region[25]. But other, more occasional quarrels continued to crop up regarding specifically St. Eustatius. In 1776, for example, the British government had lodged a formal protest when an American cargo ship fitted out for naval warfare, the “Andrew Doria”, had sailed into the road of St. Eustatius flying the “Great Union Flag”, representing the newly constituted United States, and taken the ritual salute from the fortress of Oranja. The episode was reported by the British governor of nearby St. Christopher as a serious diplomatic offence to Great Britain, and both Parliament and the executive demanded an official apology from the States-General, threatening to recall the British ambassador. But nothing further came of it, and in spite of a massive deployment of British naval power, St. Eustatius, “that famous deposit of wealth and mart of traffic”[26], continued to pursue its commerce with the ex-colonies of North America. The Jewish merchants were particularly active in this respect, thanks in part to their ties with the Sephardic communities in British North America. These communities had generally come out in favour of the Revolution, in part because they benefited from safeguards similar to those set out in the Jewish Naturalization Bill, adopted by the British Parliament in 1753 but abrogated in Britain itself the following year. In this support they reflected the position of the Jewish communities in Britain, who in 1776 held an official gathering to express their solidarity with the American rebels[27], an event which had only added to the resentment felt by British authorities vis à vis the Jews, who were known to be the chief protagonists in contraband trading in many different places.

3.

16. On 3 February 1781, just a few weeks after the declaration of war on Holland – so soon afterwards, in fact, that Burke believed that the operation had been carefully planned well before the official onset of hostilities – an unduly powerful British naval expedition under the command of Admiral Rodney, carrying a contingent of Royal Marines under General John Vaughan, appeared in the bay of St. Eustatius in full fighting trim, where many mercantile craft of various nationalities were lying at anchor, and ordered the island to surrender[28]. The governor De Graaff, with his garrison of 50-60 men, needed no convincing, and surrendered “without resistance and at discretion”. From a military standpoint it was a thoroughly insignificant episode, bringing no distinction to one side or the other. But on disembarking Rodney, Vaughan and the troops came across a veritable Aladdin’s cave: goods of every description stockpiled in warehouses, shops, stores and the holds of over 130 ships moored in the bay, and even amassed here and there at the roadside, amounting to what Rodney in a conservative estimate put at over two million pounds sterling, or well over three million in other reckonings[29]. With the capture of six warships into the bargain, these were indeed spoils that went far beyond anyone’s expectations, resulting in gloom and despair in Holland[30], where the course of events was monitored by the Gazette de Leyde, and public manifestations of enthusiasm in Britain. Yet what exactly took place after the British occupied the island ?

17. Entering fully into the role of conqueror, Rodney took command in the island and treated all he found there as prisoners of war, confiscating ships, property, warehouses and merchandise of every description in the name and interests of the British Crown, according to the terms of the surrender. As he was to declare at a later date, “The island of St. Eustatius was Dutch, everything in it was Dutch, everything was under the protection of the Dutch flag, and that as Dutch it shall be treated is the firm resolution of a British Admiral, who has no view whatever but to do the duty he owes to his King and country”[31]. The orders issued by the King on 20 December 1780 had been clear on this matter[32] and the Admiral had duly exhibited them in ordering the surrender: all goods were to be seized and placed at the disposition of His British Majesty[33]. On 4 February he wrote to the Secretary of State: “It is a vast capture; the whole I have seized for the King and the State and I hope will go to the public revenue of my country”, adding that he harboured no aspirations to personal gain, even though he was entitled to a one eighth share as the “lawful prize” of a capture, and that he awaited orders concerning what was to be done with the booty[34]. Further seizures took place over the following days as Dutch convoys which had recently set sail from the island or were just arriving were intercepted. Two days later Rodney was able to write to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Germain: “the capture is immense and amounts to more than I can venture to say. All is secured for the King, to be at his royal disposal”[35]. Again he wrote to Lady Rodney on 7 February, “The whole has been seized till his Majesty’s pleasure shall be known,” adding with virtuous complaisance, “no man has been allowed to plunder even a sixpence”. On 10 February he was still waiting to learn the royal wishes as to the destination of the “gracious bounty”, and over the next few days preparations were set in train to organize a convoy that would be “extremely valuable, more so, I believe, than ever sailed to Great Britain, considering its number of ships”[36], to ensure a safe passage for the treasure of St. Eustatius. Rodney and Vaughan were determined not to leave the island until the despatch operations had been completed. They were anxious to avoid all irregularities and acts of favouritism or peculation in the “business of the capture”, which was to be conducted according to clearly established procedures. Agents were appointed to supervise the evaluation and sale of the confiscated property both in loco and on arrival in Britain[37]. Part of the seized provisions and stores were earmarked for the British armed forces currently deployed in North America and the West Indies.

The awaited royal instructions, dated 30 March 1781, finally reached Rodney and Vaughan some time in April, preceded by notes of praise and approval addressed to the two by the authorities at home, including one from the First Lord of the Admiralty in person, while preparations were in hand to honour Rodney for his services to his country[38]. In practice the instructions set out the Crown’s renunciation of its rights over the goods seized from the enemy in favour of those responsible for the capture (the forces of the Royal Navy and the Royal Army with their respective commanding officers); enjoined a proper respect for the property of the residents, including the produce of the land, houses, slaves, personal effects, cattle and tools, as well as goods belonging to British subjects which had been legally exported to the island or could be legally imported into Britain; and in short gave a decidedly restrictive interpretation of the goods that could be legitimately confiscated and shared out[39].

18. It is not easy to establish to what extent Rodney’s conduct prior to his reception of the royal instructions had complied to these indications which did indeed, “from a source of wisdom and moderation”[40], considerably reduce the categories of goods susceptible of confiscation. Under the regime of occupation he set up there was evidence of rigour but also of mere cruelty and lack of discrimination in treating the various categories of people and deciding where to draw the line in the confiscations and seizures, which ended by being indiscriminate and taking on an inquisitorial nature in extending to the ledgers, trading bills, inventories and even petty cash belonging to individuals. As can be seen in the correspondence of a high-ranking officer full of his patriotic duty, Rodney nurtured a rancorous hostility towards the enemy, in particular those of his countrymen who had grown rich by means of illicit wartime trading to the detriment of their homeland. Moreover he was convinced that the illegal trading based on St. Eustatius, “an asylum for men guilty of every crime and a receptacle for outcast of every nation”[41], had allowed the American rebels to extend the war beyond its due term and enabled the French to get supplies to their own islands. This surely explains why he was so exultant at the severe blow dealt not only to the city of Amsterdam – British diplomacy had been careful to distinguish between its responsibility and that of the States-General of Holland, blamed only for not succeeding in containing the influence of the Amsterdam magistrates [42] – but also to Holland at large and to “many of our people in London”: “It will teach them for the future not to supply the enemies of our country with the sinews of war: they suffer justly”[43]. What his intervention had effected had been a “just revenge of Britain” against not only the treacherous Dutch but also all the nation’s enemies:

France, Holland and America will most severely feel the blow that has been given them; and English merchants who, forgetting the duty they owe their King and country, were base enough, from lucrative motives, to support the enemies of Great Britain, will, for their treason, justly merit their own ruin[44].

In the light of this attitude, it is clear that the British conquerors did not limit themselves to merely confiscating enemy goods: their purpose was quite explicitly to punish and exact revenge, as transpires unequivocally from Rodney’s declaration that he would not leave the island until “the Lower Town, that nest of vipers, which preyed upon the vitals of Great Britain, be destroyed”[45]. Similarly eloquent, although not in fact borne out by subsequent developments, was the expression of his satisfaction at the job done on the eve of his departure:

The island is put in a state almost impregnable and I hope [...] Vaughan and myself will leave it, instead of the greatest emporium upon earth, a mere desert, and only known by report; yet, this rock of only six miles in length and three in breadth, has done England more harm than all the arms of her most potent enemies, and alone supported the infamous American rebellion[46].

In speaking of the British subjects (whether at home or in the colonies) who had betrayed their nation and were shipped home accused of high treason, he gave vent to biblical sentiments: “Providence has ordained this just punishment for the crimes they have committed against their country”[47]. People of various other nationalities were also harshly dealt with, exceptions being made only for French agents and merchants. The protest lodged by the governor of Martinique at the severity shown to his fellow countrymen elicited a firm denial from Rodney. He subsequently stated that his aversion regarded exclusively the “guilty American merchants and the equally guilty Bermudian and British”, who in any case had been allowed to keep their personal effects, adding that although the French had indeed had their goods confiscated, they had been treated with the greatest respect and allowed to leave with their private possessions and even their slaves. He undertook to reserve the same treatment for the Dutch merchants, even though his personal opinion of the governor de Graaff was scathing[48]. The only people for whom he showed genuine respect were the owners of the sugar plantations, few of whom he found to be involved in illegal practices, and also the inhabitants of the other two Dutch islands captured in the operation, Saba and St. Maarten, whom, he said, “I believe will prove loyal subjects”[49].

19. Naturally the correspondence of Admiral Rodney, published in 1790 for the part that concerned the case of St. Eustatius and more extensively forty years later, but in both cases with an ostensibly apologetic intent[50], cannot be considered a reliable source for a reconstruction of these facts (which in any case is not our prime concern). The first editor, Mundy, stated clearly that in some cases he was only publishing excerpts, so it is not possible, without embarking on painstaking cross-referencing, to rule out the possibility of this or that letter having been toned down or censored (as Jameson appears to suspect) and that the whole collection is the product of partial selection[51]. Obviously in both his official and private letters Rodney sets out to justify his conduct, showing that it was perfectly in line with the orders he received, motivated exclusively by his sense of duty and quite devoid of any considerations of self-interest. Concerning the destiny of the residents and riches of St. Eustatius, he never failed to emphasise the will to be impartial and the pursuit of justice, while making no mystery of his personal sentiments. We would hardly expect to come across an explicit admission of acts of gratuitous, indiscriminate violence by British troops vis à vis goods or people of whatever nationality. Having said this, it is nonetheless significant that in none of the letters that have been used by historians[52] do we find specific, exclusive references to the Jews of St. Eustatius – not extending to other national groups – such as to account for the particularly harsh treatment that, as we saw at the start, was meted out to them alone on 13 February. What is certain is that a hundred or so heads of Jewish families were summoned without forewarning and subjected to humiliating perquisitions in the conviction that they were concealing on their persons substantial riches, resulting in the confiscation of goods, monies and personal objects. As we have seen, thirty of them were immediately taken from the bosom of their families, embarked without warning or the possibility of taking any personal effects with them, and taken to the nearby British possession of St. Christopher, where in fact they were treated with generosity[53]. All the others were kept under lock and key for several days, and on regaining their freedom they found that all their goods had been seized and were to be auctioned off. To make the whole situation truly paradoxical, among the exiled Jews there were Americans who supported the British cause and others who had distinguished themselves for business activities that had benefited Great Britain[54]. On the other hand there is no incontrovertible evidence that the synagogue and houses belonging to Jews were torched[55].

20. There are two issues at stake here which, while not within the scope of our investigation, were crucial to the general debate at the time, prompting Edmund Burke to take a stand – which of course is the object of our interest. In the first place: did the conduct of Rodney and the British troops with respect to people and property on St. Eustatius remain within the terms of the law of nations and what was laid down by their instructions, or in any case was customary in the conduct of warfare in the 18th century, or did it degenerate into forms of illegality and unjustifiable excesses? And in the second place, did Rodney treat the Jewish population with particular harshness, revealing an attitude that we might call ‘anti-Semitic’?

21. On the first point, while taking into account both the Admiral’s official declarations and the subsequent developments, in particular the numerous law suits taken out by British subjects who believed themselves to have been unjustly penalised and which had contradictory outcomes, recent historiography has tended to recognise that, although no looting of St. Eustatius was carried out, “indiscriminate” acts of abuse of power and violence did in fact take place, for unacceptable reasons of mere retribution not endorsed by instructions received from the government, and also for more prosaic reasons of private interest associated with the percentage of the booty that was customarily due to the protagonists of a conquest[56]. There is however no evidence that Oranjestad was razed to the ground, even though Rodney explicitly hoped it would be on more than one occasion[57].

22. In terms of the treatment of the Jews, there is no doubt that the episode, which certainly involved brutality, has taken its place in the tragic gallery of Western manifestations of anti-Semitism[58]. One must of course be cautious about using an adjective that came into existence in the late 19th century about forms of conduct dating from a hundred years earlier[59], but in any case it is by no means certain[p1] that Rodney behaved in a way that can be appropriately described as anti-Semitic. Even a partisan commentator like the author of the Jewish People’s Almanac (1981), who is prepared to endorse forms of violence for which there is no sure evidence, reaches the conclusion that “although the lower town of St. Eustatius and all its commercial buildings were torn down by Admiral Rodney in 1781, he cannot be charged with anti-Semitism”[60]. As we have seen, the correspondence, with all the necessary caveats, seems to bear out such a conclusion, especially in view of the fact that the hostility and desire for revenge it points to were never aimed specifically at the Jews but rather against all those “villains”, “vipers” and “thieves”, above all of British nationality – some of whom undoubtedly Jewish – held guilty of damaging the interests of the nation and indeed of renouncing their “allegiance” to the Crown by becoming Dutch “burghers”[61]. We must however also place on record that, in letters written before the events at St. Eustatius, Rodney showed himself capable of using particularly disdainful expressions concerning the Jews, referring to them as people who “will do any thing for money” and “who carry on a most pernicious commerce”. Some years previously he had seized several cargo ships belonging to Jews off Jamaica[62]. Finally we can add that the harshness shown to the Jews collectively – and not only to those among them who were British subjects – did not extend to other residents of St. Eustatius taken captive by the British. In this respect the petition presented to Rodney and Vaughan in the name of the “people of the Hebrew nation resident in the island of St. Eustatius”, as early as 16 February 1781, is significant and worth examining[63]. The authors, clearly Jews who had remained on the island, some of whom defined themselves “natural-born subjects of Great Britain”, paid a general tribute to the loyalty of their fellow Jews to the Crown and the British constitution. They praised the spirit of tolerance that characterised British constitutional principles vis à vis creeds which, like the Jewish religion, preached peace and obedience to the establishment. They asked to know on the basis of which crimes their families had been condemned to banishment and confiscation, declaring it unthinkable that on a “British island” (as St. Eustatius had to be considered following the conquest), mere profession of the Jewish religion could be considered a crime. In saying as much they were clearly raising the suspicion that it was precisely this consideration, and no other, that lay behind the hostility and cruelty shown to them, while at the same time declaring their submission and loyalty to the British authority that held sway on the island. The petition, which was in effect an explicit (albeit ambiguous) request to be allowed to confirm (for those who were British subjects by birth) or to take ex novo an “oath of allegiance”[64], was received with supreme indifference, eliciting no reply whatsoever (as indeed was the case for another petition presented by the British merchants of St. Christopher). In fact, in view of all the facts we have set out to this point, the historian who has most recently dealt with this question does not seem to be wide of the mark in identifying an element of anti-Semitism in the conduct of Rodney[65].

23. Whatever the verdict of contemporary historiography on the basis of the available sources, there is no doubt that the victims of the British impositions immediately made their voice heard in both Amsterdam and London, also because, as we have seen, there were a number of British subjects among them who resided in the nearby islands of Antigua and St. Christopher, as well as owners of warehouses, cargoes and activities on St. Eustatius. It was the latter who presented to Rodney two protest memorials[66], shortly followed by the “West India merchants and planters” in London[67]. Alarmed at the possibility of French reprisals, their representatives met the Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord Germain, and on 6 April 1781 presented a petition to the King which had been drawn up with notable acumen[68]. Thereafter other voices were raised in protest from provinces of the Empire, including that “little piece of provincial oratory” comprising an address sent to the King by the assembly of the representatives of St. Christopher through their colonial agent in London in November 1781[69]. By this date the affair of St. Eustatius had already come to the notice of Parliament. It was here, in May 1781, that Edmund Burke delivered his first speech (a second followed in December) urging an enquiry into the events of St. Eustatius, a motion that was eventually rejected by the Commons by 160 votes to 86. The speech comprised an impassioned defence of the victims of Rodney, and the Jews above all, and a resolute indictment of both the British commanding officers and the government[70].

4.

24. The taking of St. Eustatius came to the attention of Parliament at a delicate juncture in Great Britain’s international standing, when half of Europe was declaredly hostile, and at a particularly difficult moment in what had started out as a conflict within the Empire and degenerated into a general European war. The future of the conflict in North America was uncertain. The French fleet in the West Indies represented a very serious threat, and in fact proved decisive over the following months in the events surrounding the siege and surrender of Yorktown. Thus the movements of Rodney’s fleet in the Caribbean had a decisive role to play, and his course of action did come in for considerable criticism. Referred to by the demeaning epithet “storekeeper”, he was denounced first for lingering in St. Eustatius for three months, intent on amassing as much booty as possible to share with Vaughan and failing to engage with Admiral de Grasse in the Caribbean[71], and then for turning for home, allowing the French not only to set off unimpeded for Chesapeake Bay but also to take possession of a number of islands in the archipelago, including St. Eustatius itself, which flew the French flag from November 1781 to November 1784[72], whereupon it reverted to the Dutch. We can note that the island promptly regained its former prosperity following the British occupation. By 1790 its population numbered almost 8000 residents, and there was even an English language broadsheet produced on the island, the “St. Eustatius Gazette”[73], indicating that the occupation cannot have had such devastating consequences as was claimed[74]. Rodney himself was able to rescue his reputation thanks to a brilliant and comprehensive defeat of de Grasse’s fleet in April 1782, although thereafter his personal finances suffered considerably from the series of prolonged law suits taken out against him by victims of the seizures on St. Eustatius.

25. In the first half of 1781 the North government was in difficulty, and within a few months of the débâcle of Yorktown it was forced to resign. Not only did the war in American show no signs of reaching a solution but it was becoming a serious threat to the security of Britain, who found herself left high and dry without any allies. The opposition, which had been very critical of the declaration of war on Holland as an unnatural act running contrary to the nation’s interests and traditional alliances, was on the lookout for topics that could fuel its attack on the government and its ministers. There is no doubt that the events of St. Eustatius could be put to good use in this respect. It is also true, however, that relations between the “West India interests” in the country and in parliament (where they could count on a powerful lobby) and the Whig opposition of Fox and Rockingham did not always coincide, in spite of their common hostility to war in America; this emerged towards the end of 1780 when Burke was forced to renounce his idea of gradually abolishing the slave trade[75]. At the beginning of 1781 Burke spoke in the House of Commons to put pressure on the government concerning the real need and interest of breaking with Holland. In the Lords too explicit criticisms were voiced deriving both from preoccupation that the renewed war with Holland had undermined Britain’s international position and discontent at the refusal of the executive and the majority in the Commons to provide fuller information about the causes of the rupture[76]. Further questions out of which the opposition continued to make capital were the state of affairs in India and, in mid-February 1781, the bill to reform the civil list, which had been turned down a year previously and which Burke now again brought before the Commons. This gives an idea of the charged political climate being fostered by the opposition in which Burke took up the episode of St. Eustatius. He made a first, major speech in parliament on 14 May 1781 with a view to obtaining all the necessary documentation concerning the conduct of Rodney and Vaughan during the capture and occupation of the island[77]. This was little more than three months after the events and the petition presented by the Jews who had been evicted from St. Eustatius, the first in a series of petitions addressed by other categories of victims to Rodney and the King.

26. The interest of this speech – which justifies its inclusion alongside Burke’s more celebrated interventions on the conflict with the American colonies and on the Indian question – lies not so much in its immediate political valence as in the fact that Burke’s criticisms of the British commanding officers and the executive are backed up by motivations and reflections on the topic of war, conquest, the rights and duties of conquerors and conquered and the law of nations which are of considerable significance for anyone investigating Burke’s philosophy and indeed British political culture concerning empire and its government at the end of the 18th century. The first part of the speech was devoted to a historical and anecdotal reconstruction of the events, accompanied by observations and judgements, leading up to an impassioned denunciation, above all in humanitarian terms, of what he maintained was “a cruelty unheard of in Europe for many years, and such as he would venture to proclaim was a most unjustifiable, outrageous and unprincipled violation of the laws of nations” (p. 302). This was what the wholesale, indiscriminate seizure of public and private goods carried out by Rodney amounted to in his opinion, after the enemy had surrendered without offering resistance or claiming conditions, submitting to the clemency of the victor, only to find themselves the victims of unjustifiable cruelty. It had been a “complete act of tyranny [...] unparalleled in the annals of conquest”, perpetrated moreover at the expense of private individuals of various nationalities, indiscriminately lumped together as ‘enemies’, using methods and actions that, with his customary rhetorical verve, Burke denounced as not befitting a free nation of the civil and [p2] polite Europe in an “enlightened age”, but rather the barbarity of former times. The words he used to describe the events left no room for misapprehension: it had been a matter of looting, plunder, tyranny beyond all imagination. He argued that the Jewish victims constituted a special case, since “the poor Jews at St. Eustatius were treated in a worse manner, if possible, than all the other inhabitants”, finding themselves victims of persecution and banishment. These were precisely “the people whom of all others it ought to be the care and the wish of human nations to protect” (p. 304). He resorted to particularly dramatic language to describe the hardships they had been subjected to, providing details of individual cases that he could only have learned from eyewitness accounts. The lack of a national government, a state apparatus, a specific legal system and indeed of permanent residency were not evoked here to advance the cause of emancipatory measures but rather to argue that the protection of the Jews was a precise duty imposed by the humanitarian sentiments binding all “civilised nations”: “Humanity then must become their protector and ally” (p. 304). We are not confronted here with the common ambiguous image of ‘diversity’, all too prone to racist interpretations. Instead Burke deftly sketched the portrait of a typically cosmopolitan race, whose vices were actually to be attributed to their historical condition of dispersion, subalternity and proscription, and which nonetheless was entitled to the claim of “utility”. The scattered Jewish communities were like the ganglions of a global system through which the lymph of credit could spread and nurture the civilization of world trade. Speaking out in defence of the Jews meant guaranteeing the very idea of modernity based on exchange and credit. Without in the least passing over the other victims of confiscation and banishment – whether Americans, Dutch, French or British – Burke gave particular prominence to the fate of the poor Jews at St. Eustatius, those “transported beggars” whose piteous condition derived from the difficulty of obtaining the legal redress that other communities could hope to secure on the basis of existing rights and procedures. Such a consciousness of the civil rights of Jews with varying origins constitutes an element that we must highlight, even as we ask whether it finds a counterpart in Burke’s pronouncements on the condition of the Jews in Great Britain.

27. The problem of the Jews’ civil status does not in fact ever seem to have been an issue which Burke took up by engaging in political initiatives, even though he did deliver appeals in favour of tolerance towards the Jews in common with Moslems and non-Christians. These appeals were unequivocal, although not perhaps as systematic, or backed up with the same sort of practical initiatives, as those in favour of “dissenters” and Catholics, in particular in Ireland. In general Burke, although a supporter of a national “religious establishment”, was at pains to speak out repeatedly in favour of a broad religious tolerance, manifesting an unmistakably liberal outlook on the matter. In his opinion “dissenters” should have enjoyed considerably greater freedom than that granted to them under the “Toleration Act” introduced under William III. He was even able to say that “my ideas of toleration go far beyond even theirs [i.e. of dissenters] ”.

I would give – he told a correspondent – a full civil protection, in which I include an immunity from all disturbance of their public religious worship, and a power of teaching in schools as well as temples to Jews, Mahometans and even Pagans; especially if they are already possessed of those advantages by long and prescriptive usage, which is as sacred in this exercise of rights, as in any other[78].

On another occasion, when writing to the Church of Scotland minister John Erskine (1721–1803) on the subject of the latter’s virulent stand against the proposed abrogation of anti-Catholic legislation in 1778, Burke stated quite categorically that “I should think myself inconsistent in not applying my ideas of civil liberty to religious”, explaining that his explicit predilection for Christianity could not prevent him from harbouring “that respect for all the other religions, even such as have mere human reason for their origin, and which men as wise and good as I profess”; so that “I could not justify to myself to give to the synagogue, the mosque or the pagoda the language which your pulpits bestow upon a great part of the Christian world”[79].

28. The fact that Burke did not follow up such declarations with an on-going practical engagement in favour of the complete parity of rights for Jews must not, however, induce us to dismiss his championing of the Jews of St. Eustatius as purely instrumental. We only have to consider that, following the sensational failure of the bill for the naturalization of the Jews in 1753-1754, the problem of the Jews’ civil status seemed to disappear altogether from the British political and ideological arena. Certainly no good was done to the cause by the public conversion of Lord Gordon to the Jewish faith, complete with circumcision, whom Burke subsequently ridiculed as “our protestant Rabbin”. The question was only to return to the agenda, with concrete prospects of reaching a political solution, in the early 1830s, partly thanks to the knock-on effect of legislation for emancipation of the Catholics[80]. Of course this is not to deny that there is a problem of ambiguity in Burke’s position vis à vis the Jews, particularly in view of the shades of anti-Semitism, or to put it more accurately, the expressions of anti-Jewish denigration, that occur in his later writings opposing the French Revolution. His arguments against the British radical dissenters tend to feature dismissive expressions concerning Jewry as he subscribes to the conspiracy charge, with British unitary radicalism and the French Revolution as the two faces of a single-minded Jewish attack on the divinity of Christ and traditional Christian and hierarchical society[81].

29. To return to the episode of St. Eustatius and Burke’s speech in parliament, its particular interest undoubtedly lies in the fact that the illustration and denunciation of events in the first part of the speech were followed by a much more general consideration – concerning “that right which a conqueror attains to the property of the vanquished by the laws of nations” (p. 308) – which had evident implications for the government of empire. Burke made a clear distinction between the possible excesses committed by the occupiers and the aspects of jurisprudence. While the former could be censured in humanitarian terms, he argued that there was no legal justification for them according to the terms of the right of war and prey. This took the matter onto rather uncertain terrain due to the lack, which Burke duly highlighted, of an international jurisprudence based on a codified set of laws comparable to the statutes of Great Britain. Nonetheless he was convinced that there was a law of nations, established, unequivocal and obligatory, which held good for “enlightened Europe” and informed the “rights of civilised war”. Burke listed four chief sources for this legal framework: reason, conventions between the parties, authority of the texts and precedent.

30. It is interesting to note how Burke does not actually set much store by the authority of texts, devoting very little space to them, whereas commentators on Burke’s attitude to international law invariably link him to Vattel. On this occasion too Burke refers to the Swiss jurist by name, although more on account of the latter’s general principles than because he subscribed to his doctrine[82], and his failure to cite texts is surely due to Burke’s more radical positions. In the Droit des Gens Vattel states quite explicitly that a state has the right to seize, in the form of “conquêtes” and “butin”, goods belonging to private subjects in order to weaken the enemy state, recoup the costs of war and guarantee security, while at the same time urging “modération”, “compassion”, “clémence”, “humanité” and the presumption of good faith on the part of the enemy, implying that the right to mete out punishment by seizing the enemy’s possessions is admissible only if the latter has committed conscious acts of manifest injustice[83]. For the same motives he goes so far as to justify plunder and destruction, referring to them as “terribles extrémités” to be adopted only on irreproachable grounds (punishment of a nation which has been manifestly unjust and cruel, or so as to avoid greater hazards), but which become “excès barbares et monstrueux” if committed without real necessity. Vattel concludes that “tout le mal que l’on fait à l’Ennemi sans nécessité, toute hostilité qui ne tend point à amener la victoire et la fin de la guerre, est une licence que la Loi Naturelle condamne” (p. 142). In the light of this there was nothing to guarantee that Vattel’s principles would endorse a manifest indictment of Rodney, if it could be shown that not only did he not permit plunder but had acted throughout with the precise intention of weakening the enemy and hastening the end of military operations. In one more pertinent passage with reference to the definition of the enemy’s goods (l. III, chap. V, § 75) Vattel states that “ce n’est point le lieu où une chose se trouve, qui décide la nature de cette chose-là, mais la qualité de la personne à qui elle appartient”[84]. It thus became crucial to identify the nationality of those subjected to confiscation, since the goods of British subjects (although not the Americans, of course) present on St. Eustatius could not be qualified as “enemy goods”. That these goods had been legitimately liable to confiscation depended on whether it was considered a culpable act to supply them to a market where they could be purchased by the enemy: for Rodney this was certainly the case, while for Burke it was not, although [p3] not on a theoretical basis, that is as a result of anything to be found in Vattel. If Burke believed that British subjects engaging in business at St. Eustatius had been unfairly subjected to seizures it was in view of specific, recent legislation authorising commerce on St. Eustatius, which moreover was invoked in all the British petitions referring to the Admiral[85]: “the merchants of Britain traded to St. Eustatius under positive acts of parliament” (p. 312). These laws authorised the conduct of trade that was of universal benefit for those taking part, the British included, in recognition of the fact that the island functioned as a general mart for distribution and provisioning. In true cosmopolitan, liberal and free-trade style, Burke concluded that “the island therefore was a common blessing” (p. 313).

31. Thus there were other, more cogent grounds for condemning the conduct of Rodney than those to be found in Vattel. For example it would have been crucial to invoke the precedents, or rather lack of precedents, for such a course of actions as those taken by Rodney. In reality Burke must have known perfectly well that European history did indeed contain precedents, starting from the infamous case of the “poor Palatines”, the German protestant refugees from the Upper Rhine forced to flee from French persecution and plundering during the Spanish war of succession[86]. He himself, in his Annual Register, had had to denounce, albeit cursorily, the extortions and plunders inflicted by Frederick of Prussia in Saxony in 1756 in much the same terms that he uses on this occasion[87]. It is clear that here his rhetorical strategy consisted in just postulating as an undisputable matter of fact the disappearance from the enlightened European international customs of examples of conduct that still, up until only a few years earlier, he himself had pointed out and denounced. The retaking of Grenada by the French in 1779 was an apposite episode: the British had respected French property when they took possession of the island in 1759, and the French reciprocated twenty years later. This was a pertinent precedent for rejecting any recourse to generalised seizure of goods, and Burke made use of it rather than citing anything in Vattel. He went on to use two other arguments which similarly transcend the principles set out by Vattel. One concerned the conventions established among the European nations, in a vision of a European system of juridical and political civilization that Burke was to elaborate in his later critique of the French Revolution. By these conventions, which underpinned the “right of civilised war”, conquest could be followed by the seizure of “public property” but not generalised confiscation of private property, unlike what happened on the high seas, where the seizure of the enemy’s goods, although a mark of the “inhuman species of war”, was standard practice. Burke could not actually rely too heavily on the latter argument since it was also quite common for “Letters of Marque and Reprisal” to be issued, authorising the activities of privateers, and the first point too was by no means watertight: the royal instructions communicated to Rodney and the terms of the order to surrender imparted to the Dutch island ran counter to his argument, since they explicitly stated that all conquered goods and property was to be placed at the disposition of the British Crown. Thus Burke was only really left with the one remaining argument of the four: legislation based on reason. This was what he turned to in order to put forward a vision of international relations in time of war that went well beyond Vattel.

32. Unlike the Swiss jurist, Burke was a convinced exponent of an idea of civilised war involving states rather than individuals, maintaining that “a state [...] in case of conquest does not take possession of the private property, but of the public property of the state conquered” (p. 309). This was true in the case of surrender, since surrender implied a request for protection, but Burke seemed to extend this to every case of conquest, although his arguments on this matter were not rigorous, and he was guilty of some ambiguity. The concept of civilised war implied that the goal of conquest was the exercise of political authority, not plunder, and Burke identified this political authority as an immediate and implicit consequence of conquest, in the sense of a “virtual compact” between the defeated party who sought protection and the victor who granted it in return for obedience. Here Burke departs significantly from Vattel and shows a certain affinity with John Locke, although with some distinctions. In Chapter XVI of his Second Treatise, Locke affirmed that the conqueror in a just war did in fact acquire a power (which he characterised as “perfectly despotical”) over the lives of the defeated who had taken an active part in resisting him. Such power and entitlement did not however extend to the property of those who had not played an active part in the warfare; while for those who had, this power only extended so far as was strictly necessary to secure reparations and reimbursement for the costs of warfare (Chapter XVI, §§ 177-182). Up to this point Burke could have found at least partial confirmation for positions which were considerably ahead of his time, as indeed they were for Locke’s own times[88]. Where he departed from Locke was in the type of political relationship which could derive from conquest (following a just war). Locke had clearly shown the impossibility of deriving a legitimate obligation from the use of force, and had declared the invalidity of a promise extorted under duress. The idea of a submission based on the consent of the conquered contained the paradoxical implication of attributing the authority of the conqueror to the consent of the defeated. Burke seemed to get round this difficulty by referring to the specific case of unconditional surrender. By yielding without conditions, the vanquished lost the status of a participant in the war: there was no longer a state of reciprocity, or the quintessence of warfare. Thus in the state of conquest that follows unconditional surrender he recognised a mechanism that gave rise to a pact of government, albeit a “virtual” one. This arose out of the requisite of individuals for protection and complete safeguarding of their rights: a safeguarding which for each subject or citizen derived from the trust implicit in every relationship of political subordination and which by definition ruled out any possibility of individuals’ property rights being denied them. The sovereign, and even the despot, who takes possession of the property of his subjects – whatever the mechanism by which they became his subjects – violates the trust placed in him and loses his entitlement to authority: from being a king he becomes a mere predator. Burke found it equally intolerable that, on one hand, a subject should lose any rights concerning the safeguarding of his possessions while continuing to be bound by the duty to obey; and, on the other, that a sovereign should continue to use the style of king while claiming universal rights over the property of his subjects. A conquered subject was admitted de facto “within the pale of his government” and could legitimately expect to have his property respected and protected: this was a principle of reason, of nature and indeed, as Burke had it, “inspired by the divine Author of all good” (p. 310).

33. This position carries evident implications concerning the government of empire. In Burke’s opinion the conquest of a new territory such as the island of St. Eustatius automatically meant that it came under the Imperial authority of the British Crown, and the inhabitants were “His Majesty’s new subjects”[89]. New, certainly, but possessing rights which were in no way inferior to those of the others. The government of empire – of all the territories which in various ways and by whatever mechanism were added to the British possessions – had to be based on the guarantee of the rights and liberties of all subjects, of whatever national, linguistic, cultural and religious origin. The notion that a state of warfare in a remote area of the Atlantic, far from the hub of empire, could authorise the suspension of natural rights and universal criteria of justice was every bit as inadmissible as the invocation of a “geographical morality” – claiming diversity and distance as the legitimisation for ethico-political exceptions – advanced by Warren Hastings to justify his conduct in India[90]. Burke the champion of the rights of American colonists, violated by a corrupt government, and of Indian subjects, oppressed by the despotism of irresponsible proconsuls, now took up the cause of the people of all nationalities who on St. Eustatius had been the victims of the rapacity of British officers. The latter had shown themselves to be “tyrants instead of the governors of the territories which they invaded” (p. 339).

34. Needless to say, however, Burke was not out to bring the individual commanding officers of the operation on St. Eustatius to justice. He was chiefly interested in the relationship between domestic and imperial policy and between freedom and empire. In his arguments there is no mistaking a topic which recurs in his critique of specific facets of imperial policy implemented by his country: there seemed to be a plan against the freedom and rights which extended outwards from the centre of the empire, in London, towards the periphery, consistently undermining the foundations of the constitution, as America had demonstrated and as was being shown in India too; injustice, dishonesty, wheeler dealing and illegality in every corner of the empire reflected quite consistently the corruption of the home government. The consequences for the mother country, whether the degenerate modes of exercising power were actually imported or just became gradually countenanced, would surely lead to the dissolution of the most sacred political and juridical values of the British tradition. In casting around for a potent argument to use against the government he maintained that the people truly responsible for the “shameful proceedings” were none other than “his Majesty’s Ministers”. Above all he insisted that it had not been a matter of isolated episodes but of “a whole plan” of aggression in the Caribbean whose conduct had involved unheard of harshness, violence and cruelty. And in terms that foreshadow his subsequent anti-French tirades during the years of the Revolution, he conjured Parliament to take a stand for fear that, by endorsing the government’s actions, it “should be the first to plunge Europe into all the horrors of barbarity and institute a system of devastation which not only would bring disgrace, but in all probability ruin upon ourselves” (p. 316). The object of the exercise was not to arrive at a condemnation but to set in train an adequate investigation of the events by gathering all the available, requisite information. During the debate in the Commons it had become quite clear how much was at stake, for even the pro-government speakers had explicitly recognised that it was not just a question of the property of private citizens and the reputation of high-ranking officers of the Army and the Royal Navy but the fate of the government itself. And in his final summing up Burke delivered a telling shaft emphasising the incompatibility between the survival of the empire and government policy when he posed the rhetorical question “whether we must part from the minister or from the empire” (p. 340).

35. We can say at once that Burke’s motion was rejected by a large majority in the Commons in May 1781; and a second, broader motion (calling for a select committee to investigate not only the seizures but also the way in which the confiscated goods had been sold off) was also rejected by a comparable majority in December of that year when the subject was once again debated in the Commons, in the presence of Rodney and Vaughan. Burke’s speech on this second occasion included no particular new elements with respect to what he had set out in May. The only new argument – that had been already formulated when the affair was being discussed on the empire’s fringes, and that [p4] possibly Burke derived from those very sources[91] – was that an end to the war was indeed one of the “blessed consequences” of the capture of St. Eustatius, but, on account of Rodney’s inertia, in just the opposite sense to the one contemplated by the government, that is because the French fleet had been left free to collaborate in the blockade of Cornwallis in Virginia[92]. This second speech is nonetheless noteworthy for its greater vehemence, undoubtedly owing to Burke’s determination to bring the government, in grave difficulties since Yorktown, to its knees. He was particularly ruthless towards Lord North, whose stand in defence of Rodney’s patriotism brought the full force of Burke’s indignation down on his head: “He ! dare talk of British feelings ! He ! that has ruined the British empire and wasted its blood and treasure”[93].

5.